There’s a greater appreciation of ghost towns in the Kootenays than most places.

“For a place that’s relatively small, the amount of history generated is rather remarkable,” says Greg Nesteroff, a journalist with the Nelson Star who has researched many of Kootenay’s ghost towns.

“The history itself is so fascinating and diverse. It’s not just railway and foresty or mining, there’s all of those things.”

In a boom-and-bust region where towns would quickly come and go, there are many ghost towns that dot the highways.

Most are lost to history – but one has an eight-foot-high monument in its honour.

Well, sort of.

The word cenopath is Greek for “empty tomb,” and you can find plenty of them throughout Canada. From coast-to-coast, there are monuments, many of which were erected in honour of those who died in World War I.

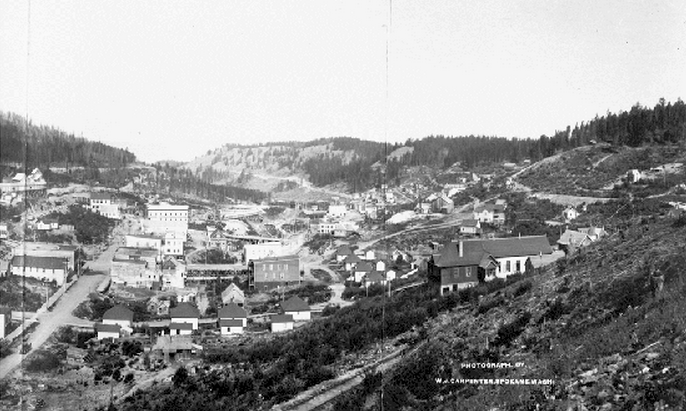

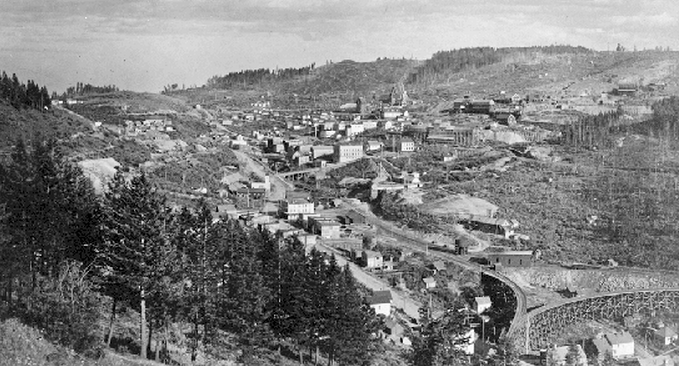

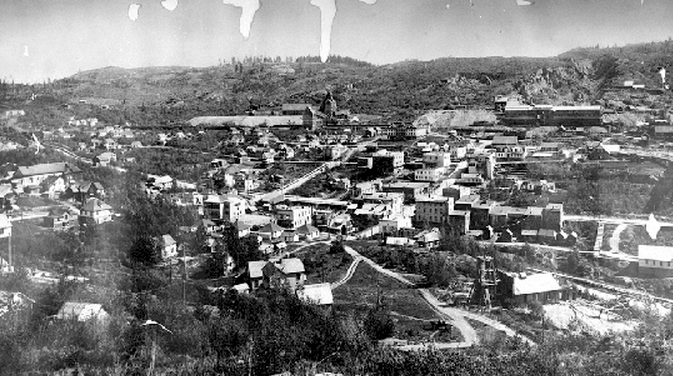

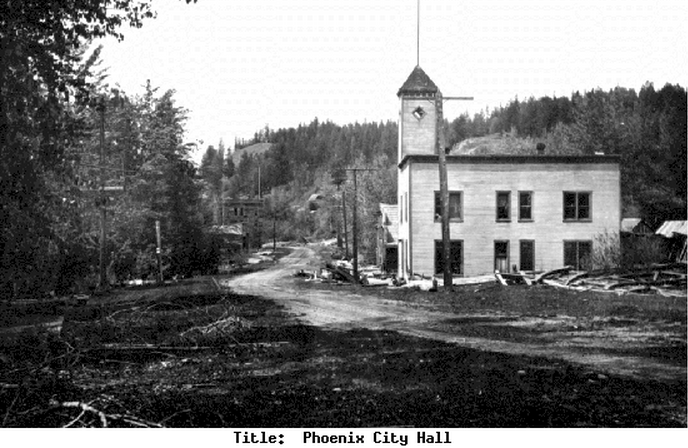

One of them is in Phoenix, B.C. Today, it’s best known as a ski hill sitting between Greenwood and and Grand Forks. A century ago, with a population of nearly 4,000, it had equal standing with them in terms of population.

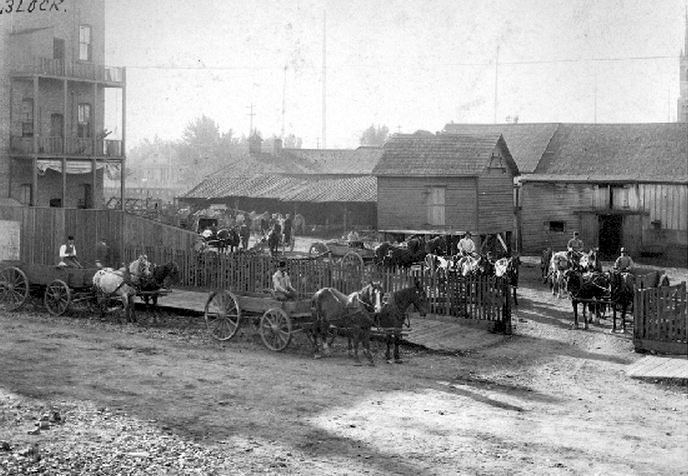

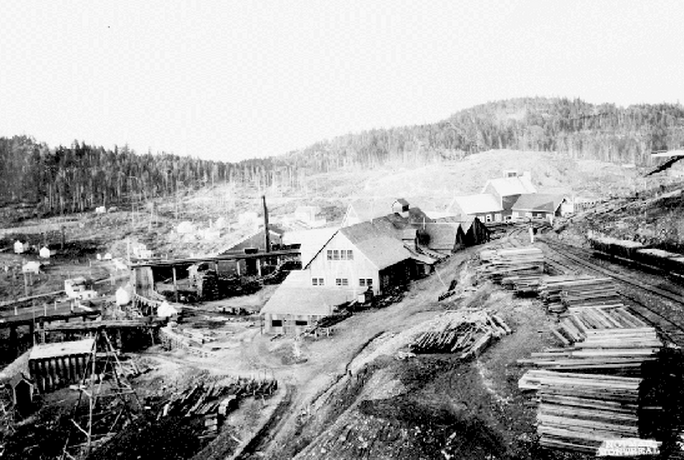

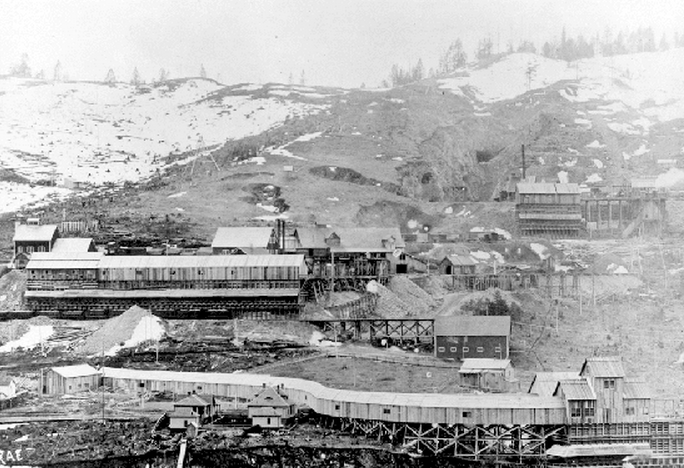

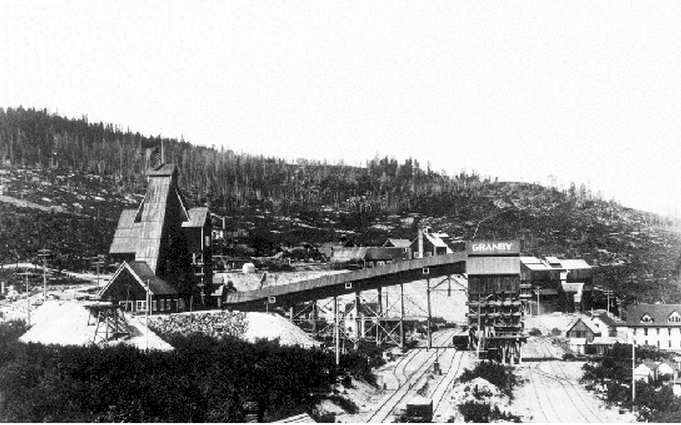

PHOTO GALLERY: The town of Phoenix. All photos courtesy of BC Archives.

“It was a certainly a fledgling city,” says Nesteroff.

“It had a sense of permanence with all the amenities, you would find the major centres. The rise and fall of the town all played out over 20 years.”

Get breaking National news

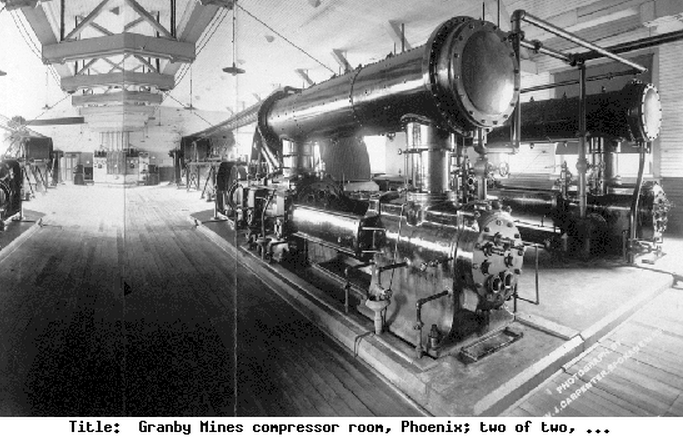

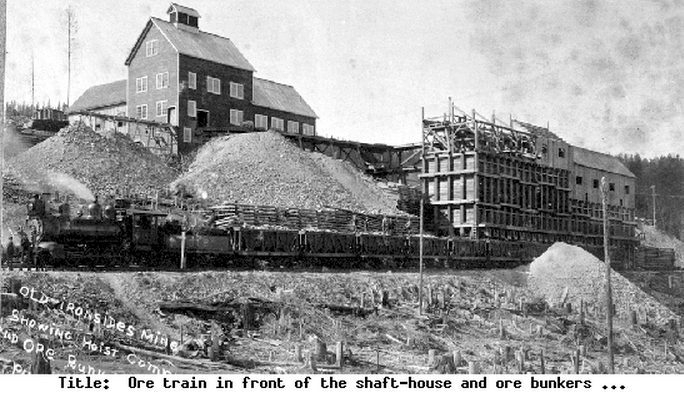

Incorporated as a town in 1898, Phoenix had one of the most productive copper mines in B.C. for nearly two decades. It was of a company town, owned by Granby Consolidated Mining, which created lavish towns for its workers and their families.

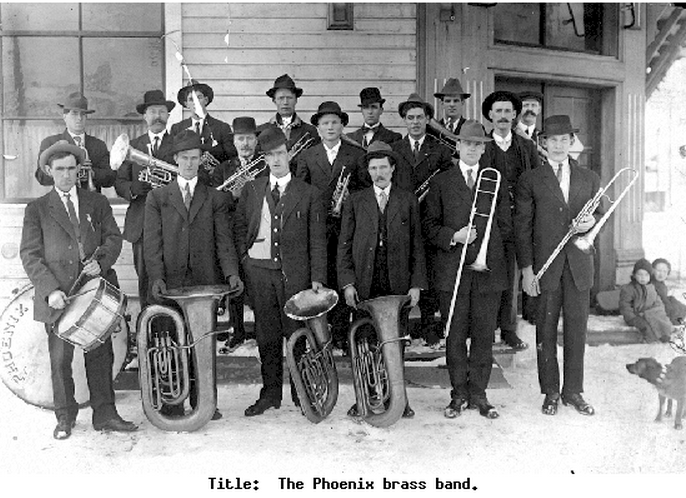

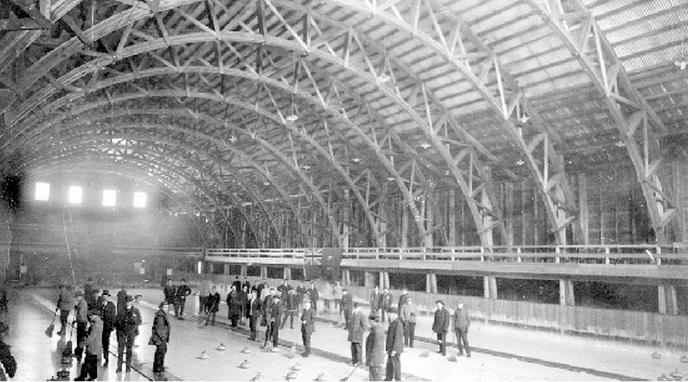

There was a skating rink, a weekly newspaper, several stores – even a brass band.

In 1911, the Phoenix Hockey Club won the McBride Cup, given to B.C.’s top hockey team. They challenged the Ottawa Hockey Club for the Stanley Cup – but the team declined, saying it was too late in the year.

In the end, the fate of Phoenix was like so many other mining towns – when the price of copper crashed, the mine was shut down. However, when Granby announced the shutdown, the townsfolk were planning a cenotaph to honour 15 people from Phoenix who died in the First World War.

To make it a reality, the lumber and and iron were sold from the skating rink.

$1200 was raised, enough to build the cenotaph and donate $400 to the Legion in Grand Forks. By the time it was erected in 1920, the town buildings with any value were being shipped away.

“I’m trying to think if there’s another ghost town that has a cenotaph , and I can not think of it,” says Nesteroff.

The mine was reopened in the 1950s, operating as an open pit for nearly 20 years, before shutting down again. Today, Nesteroff says there are only a few people alive who ever lived in Phoenix. Only the mine pit, a decaying graveyard, and a few destroyed shacks remain.

Along with the cenotaph .

“It’s all the more poignant because it’s not just the men for the first world war, it’s a monument to the town of itself.”

“Ghost Town Mysteries” is a semi-regular online series exploring some of the strange sights from B.C.’s past.

The old trolley buses of Sandon

The swimming pool of Mount Sheer, B.C.

The stolen lightbulbs of Anyox, B.C.

The 30-year slumber of Kitsault, B.C.

Bradian, B.C., a ghost town for sale

Comments