VANCOUVER – Tiny, ancient hedgehogs and pre-historic tapirs once roamed the Bulkley Valley in northern British Columbia, many millenia ago when the area was a temperate oasis from the surrounding tropics, says a new study.

An expedition of scientists found fossils of the 50-million-year-old mammals in Driftwood Canyon near Smithers, B.C. – the first mammal remains found preserved in the well-known fossil beds of the provincial park.

READ MORE: New BC fossil site could be world’s most important

A fingernail-sized hedgehog jawbone was found in 2010 and a hand-sized tapir jaw was discovered the following year by expeditions led by Brandon University in Manitoba, said university biologist David Greenwood.

“In the case of our little hedgehog, perhaps it was being eaten by an owl or some other predator,” Greenwood said.

The area was once a lake bottom that has produced plant and insect fossils from the early Eocene era and the team believes the hedgehog remains were dropped there by a predator.

“It might be that that was what happened – it was an owl’s meal and it coughed up the pellet and that’s how it ended up in the lake. That’s pure speculation but that seems a reasonable supposition.

“Our tapir though, that was probably where it lived – in a swamp – and it just died there and preserved.” he said of the rhino-like creature that was about the size of a medium dog.

Get daily National news

Finding the fossils was just the first hurdle. Identifying them was another.

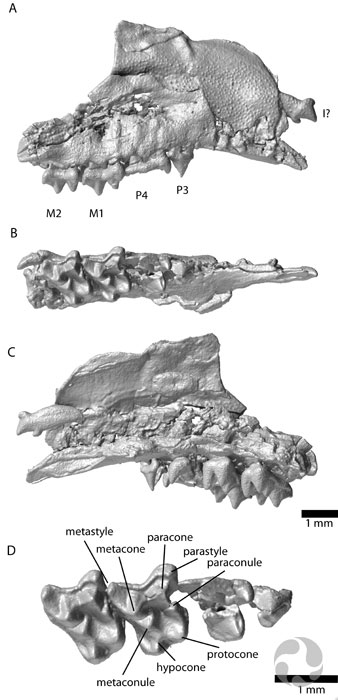

The hedgehog jawbone was broken into two slabs of rock. The animal would have been about 2.5 centimetres long and the jawbone is only about a centimetre, so it was not possible to extract the remains from the rock and reassemble them, as normal.

Enter technology.

The specimen was sent to Natalia Rybczynski, a palaeobiologist at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa and co-author of the study.

“We didn’t touch the specimen at all. You could not handle it,” she said.

A micro CT scan was used to create a 3D version of the remains, which were then reassembled into a virtual version that could be compared to existing specimens. It was a species previously unknown to science.

“It’s a really interesting time in the evolution of mammals because you have the earliest version of so many lineages, so many modern lineages. The earliest versions of carnivores and the earliest version of bats are appearing at this time,” Rybczynski said.

READ MORE: Scientists find ancient parasite egg linked to disease that still infects millions of people

The Heptodon, an ancient relative of modern-day tapirs, was identified by Jaelyn Eberle, a geological scientist at the University of Colorado and lead author of the study, published in the latest issue of the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Although hedgehogs and tapirs no longer call North America home, they are known to have existed and may have even originated here, Rybczynski said.

Once a lake bottom, Driftwood Canyon has preserved pre-Ice Age history in shale formations that have produced fossils of plants, insects, fish and – now – mammals that inhabited the region in the early Eocene period.

“These new mammals fill out our picture of this environment,” Greenwood said. “This is part of our story. For this time period, the Eocene, we know very, very little about mammals across Canada.”

It also provides a clue to how Earth’s climate has changed in the past and may change in the future, he said.

Greenwood and his colleagues hope to mount another expedition to Driftwood Canyon next year.

For now, the hedgehog jaw remains at the Canadian Museum of Nature but it will be sent to the Royal British Columbia museum in Victoria in the near future.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.