TORONTO – We may think that the ozone hole is a thing of the past, but new research has found four new gases in the atmosphere that could potentially contribute to the depletion of the ozone layer.

The paper, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, found that more 74,000 tonnes of three new chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and one new hydrochlorofluorocarbon (HCFC) have been released into the atmosphere.

And nobody knows where they came from.

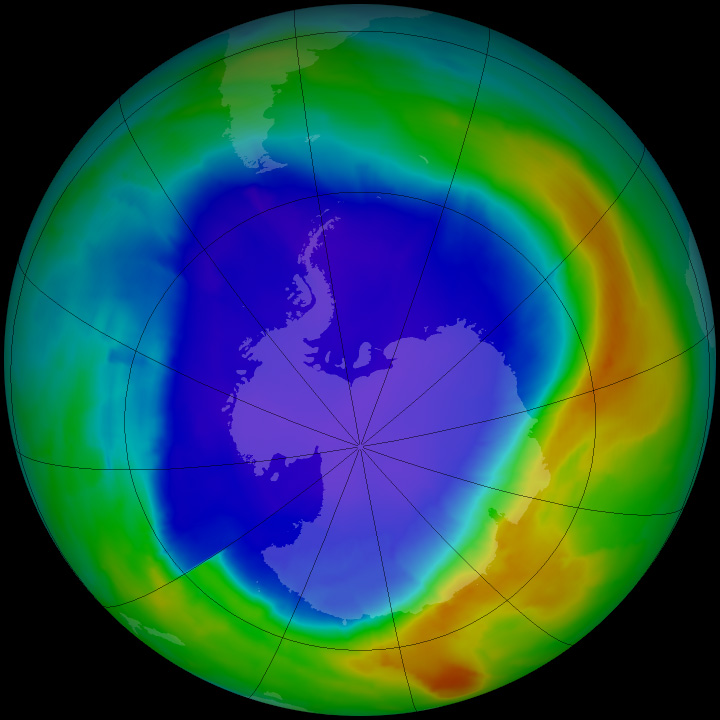

The ozone layer, found in the stratosphere, protects us from the harmful effects of the sun’s ultraviolet radiation. CFCs basically eat away at the ozone, creating a large hole, dubbed the ozone hole, found mainly at the south pole.

In the 1980s great quantities of CFCs were found in the atmosphere. The new measurements were taken by comparing air samples from today with the air trapped in polar snow called firn. Firn keeps a history of air in the atmosphere.

The research showed that these four gases have been released into the atmosphere recently, with two that are accumulating rather quickly.

“In terms of their levels, they’re actually not an immediate threat to the ozone layer,” Johannes Laube from UEA’s School of Environmental Sciences at the University of East Anglia, England, told Global News. Laube was the lead researcher.

“However, it’s surprising to find that there’s more of them out there, because there haven’t been any new CFCs detected since the 1990s…The worry is that, two of them — one CFC and the HCFC — actually are increasing.”

In 1989, the Montreal Protocol — designed to phase out CFCs — was put into force by the United Nations. More than 100 nations have signed the agreement.

Get breaking National news

In 2006, the ozone hole was the largest ever observed — at 26 million square kilometres. But since then the ozone hole has shrunk considerably due largely to guidelines in the Montreal Protocol.

READ MORE: South Pole ozone hole slightly smaller this year

“There are still plenty of ozone-depleting substances in the atmosphere to cause ozone depletion each year in the Antarctic in particular,” Steve Montzka told Global News. Montzka has been a research chemist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration for more than 20 years, studying ozone-depleting chemicals.

Montzka said that the substances, however, are going down over time. The newly found CFCs, he noted, aren’t cause for concern.

“The paper’s benefit is that it identifies a few small contributors, and allows us to keep our eyes open with respect to these chemicals to ensure that they don’t become significant in the future,” Montzka said. “That people start to poke around and understand where their sources are, and what they are, and whether or not we can make sure they don’t become significant in the future.”

Laube agrees.

“The one CFC in particular has recently accelerated, which is particularly worrying, because that one is quite dangerous,” said Laube. “On a per molecule basis, that’s quite dangerous to the ozone.”

“If it were to continue on that trajectory, we would run into problems within the next decade.”

With the detection of the new CFCs, Laube said he hopes that we could avoid the increase of ozone depleting substances.

While it’s unclear where these newly detected CFCs are being created, most of the levels are detected in the highly industrialized north.

Though the Montreal Protocol — which has been adjusted five times since its inception — is in place, there are still ways that CFCs can still be used.

Laube said that there is some speculation that the new CFCs are being generated by a chemical ingredient added to insecticides. That large scale process would help to explain why there is such a large amount in the stratosphere.

“When we initially found these compounds, we thought that this must be illegal,” said Laube. “Apparently, that’s not the case, because the Montreal Protocol in its current form, has a number of loopholes.”

One of the loopholes is that CFCs can be used as a chemical ingredient in products. The thinking behind that is that the emissions would be minimal. That may not be the case.

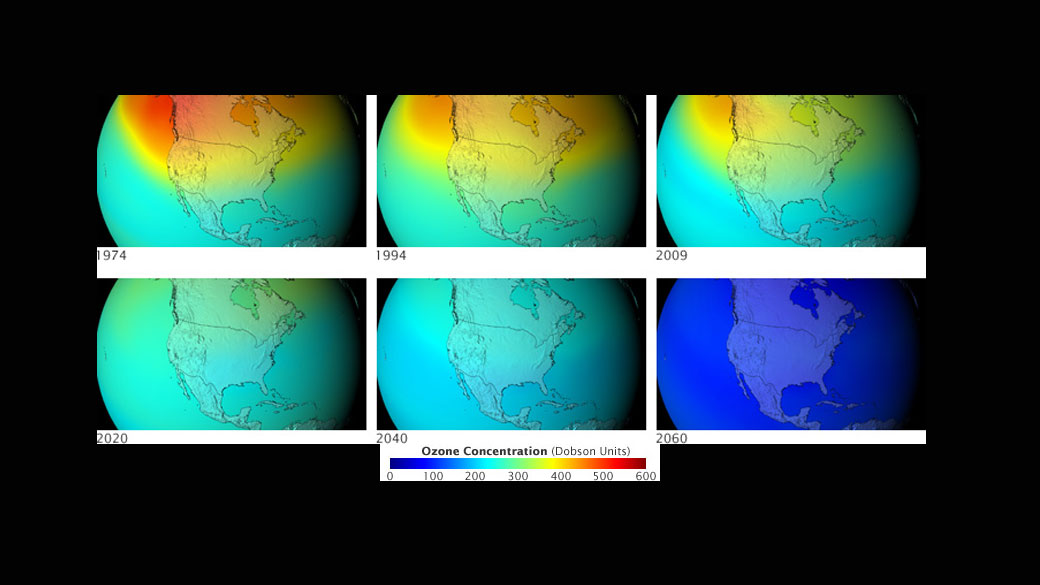

There is no call for the total elimination of all CFCs, Montzka said. There is, however, a call to get the CFCs in our atmosphere back down to levels before 1980, when scientists first began to notice the ozone hole.

“The ozone layer will recover,” said Montzka. “Even if anthropogenic emissions aren’t reduced to zero.”

The key is making sure the new CFCs don’t get out of hand.

Comments