Raw video: Throat singing gets special heritage status in Quebec

MONTREAL – Artefacts and architecture have long been a part of Canada’s cultural heritage, but this week, Quebec announced a cultural milestone.

The province has given special cultural heritage status to Inuit throat singing, the first time something “intangible” has been given this status in Canada.

“The Quebec government’s recognition of the value of our throat singing is a huge thumbs up that will surely set an example to the rest of the country,” said William Tagoona, who works with the Makivik Corporation, which aims to protect and preserve the Inuit way of life, values and traditions.

Quebec’s decision is raising questions about how cultural heritage in Canada could be affected and what it reveals about relationships between indigenous communities and governments.

What is throat singing?

Inuit throat singing or katajjaq is a type of musical performance where two women sing in rhythmic patterns, usually standing and facing one another.

“It was an activity to entertain us,” said elder and throat singer Alacie Aulla Tullaugaq in Montreal on Tuesday.

“We were hungry, particularly in winter time, so it was a means to be patient, to try and let time go by until the hunters returned.”

The game was that the first to run out of breath or miss the pace of the other singer by laughing or stopping would lose.

Reaction from the community

“As a throat singer myself, I find this announcement very exciting,” said Lynda Brown, the director of programs at the Ottawa Inuit Children’s Centre.

She said she believes that the special status of throat singing will have an impact on those that she teaches in the community.

“Throat singing is rare and many people don’t know what it is, so now that it is recognized to have cultural status, more people in the general public will get exposure to it.”

“One of the things that we do at our centre is teach about our culture, which includes throat singing,” she said.

“While this announcement won’t change what we do in our centre, it will impact those that we go out in the community to teach.”

Her hopes for what this recognition could achieve are echoed by Heather Igloliorte, an Inuit who has been living in Quebec for two years, working as an assistant professor of Aboriginal art at Concordia University.

Get breaking National news

She heard about the announcement while in Ottawa at the Northern Lights trade show, which aims to strengthen partnerships between Canada’s northern and southern business and government stakeholders.

“The arctic has been treated like a frozen treasure chest by the south for generations,” she noted.

Still, she said she hopes that this could be a step towards real protection for Inuit cultural expression and not simply a political gesture.

“This could see support towards fostering educational programs all over Quebec,” she said.

“Montreal and Quebec City have a high number of Inuit, and it would be nice if this had a positive impact on urban Inuit communities.”

Breaking the ice for cultural heritage?

What impact could this decision have on other intangible cultural heritage?

“We think it’s nice to break the ice of another cultural heritage,” said Dinu Bumbaru, Héritage Montréal‘s policy director.

“It’s an interesting start which brings us to the meaning of the word ‘heritage’; what can be transmitted from generation to generation? How is tradition passed on?”

He made reference to similar designations in countries like Japan, where intangible properties like wood cutting and calligraphy have been given special status in order to acknowledge the people who have mastered these arts, and to provide support to train and apprentice others.

“Nowadays heritage is clearly associated with other dimensions,” he said.

“Our relationship to land is not just symbolic, a city like Montreal has many sounds and places, a neighbourhood like Griffintown has its own historical soundscape.”

Intangible artworks also pose considerations for curators.

Greg Humeniuk, a curatorial assistant at the Art Gallery of Ontario, said that there were issues when curating and archiving contemporary time-based art, like that of Tino Sehgal.

“It’s hard to assert ownership over something that is intangible,” he noted.

Legal ramifications

“I’m applauding what Quebec has done, it’s an example of Quebec striking out and being ahead of the game,” said UBC law professor Robert Paterson.

Some people are excited about Quebec’s announcement because they hope that being designated a cultural heritage will protect the intellectual copyright of throat singing.

“Quebec’s recognition of one of the oldest forms of music in Canada is truly fascinating,” said Tagoona.

“Modern songs in the world are, for the most part, protected by copyright . . . it is easy to understand the need to protect one of the oldest forms of musical expression in Canada.”

However, protecting intangible heritage is not legally that straightforward.

“The concern is that intangible traditions don’t really fit into intellectual property laws,” said Paterson.

“Western copyright and intellectual property law is all about money.”

He also noted that while Quebec introduced a new cultural heritage act that had a provision for this type of intangible property in 2012, Canada has to yet to make a change to its law.

Quebec’s new act was in line with a 2003 UNESCO convention that safe-guarded intangible heritage. Canada and other countries, like the U.S., Australia and New Zealand, have not yet signed this convention.

Coincidentally, this is the same group of countries that initially voted against the United Nations’ Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Paterson acknowledged that the issue is politically and legally complicated, especially for countries with significant indigenous populations.

Politically charged

During the press conference, the president of the Avataq Cultural Institute made a direct link between the preservation of Inuit culture and the protection of Inuit land.

“This is a new step towards including Aboriginal people and to find different interpretations of Quebec identity,” said Charlie Arngak on Tuesday.

“It’s the first, but rest assured, it’s not the last.”

Arngak expressed a desire that this announcement would also lead to official recognition of Inuit lands in northern Quebec.

“I strongly hope that in the near future we will find ourselves somewhere in Nunavik to witness the announcement that our land is officially included as a part of Quebec heritage.”

Charlotte Townsend-Gault, an art history professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia, has seen how Canada’s approach to protecting indigenous cultural heritage has evolved.

“Twenty years ago, I remember the word ‘loss’ was politically incorrect. We weren’t supposed to talk about cultures being endangered; it implied a salvage-type of anthropology,” she said.

“But I’m hearing more and more from young native people these words again.”

She has greeted the announcement with “extreme scepticism and pleasure,” mixed with concern that culture “is once again being used as a kind of window-dressing.”

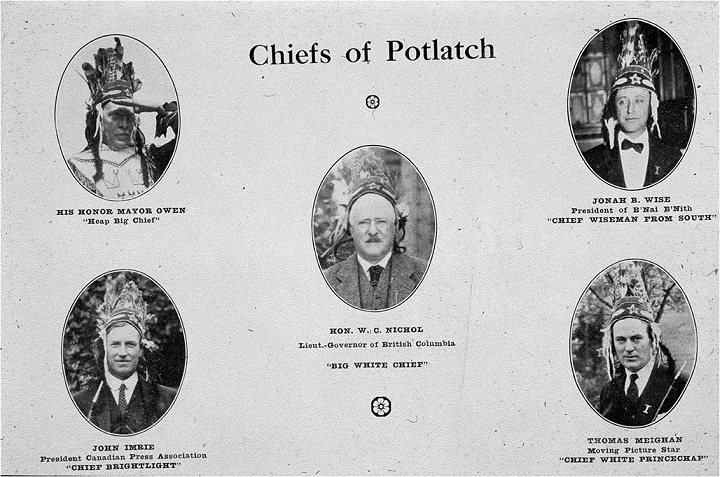

She shared an historical example of this type of cultural appropriation in British Columbia, when the potlatch, a gift-giving feast practised by indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, was banned.

Although indigenous people faced prison time for celebrating the potlatch, during an official visit from the Royal Navy in 1924, the mayor of Vancouver and other bureaucrats dressed up in beaded headdresses and had themselves photographed in a commemorative brochure announcing a “welcome potlatch.”

“Native leaders have been through so much, I admire them for standing up with such dignity, after being betrayed and hearing endless promises.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.