Maryam De Groef says she and her husband moved countries often and would always apply to be organ donors wherever they lived, but they never could have imagined having to consider that for their children.

Their nine-year-old daughter, Zeynah, died suddenly last spring after going into cardiac arrest following an unexpected allergic reaction. She was taken to the Children’s Hospital at London Health Sciences Centre in London, Ont., and after a few days in hospital was declared clinically brain-dead.

While Zeynah had allergies and asthma, her mother said the reaction that lead to her death began in response to eating nuts that she hadn’t reacted to before.

“It started off quite manageable. She said that she had a little bit of a tummy ache, but it just escalated really quickly from there,” she explained. “We were not prepared for that to be the first and last time that we used an epi-pen.”

When the family was asked if they would consider organ donation, De Groef said there was no hesitation.

“It was just so in line with her personality and what she would have done. And so in honour of her and in honour of serving mankind, we said yes.”

De Groef said Zeynah was kind, compassionate, wild and energetic. She shared anecdotes of her daughter finding a struggling bee and bringing it sugar water until it was well enough to fly off and of a bird hitting their dining room window at their home in London and Zeynah telling her mother that they needed to put something up so that birds would know not to fly into it.

Even though the little girl suffered cardiac arrest, Dr. Rishi Ganesan, who worked closely with the family, said most organs have some innate ability to recover from loss of blood flow. The team was able to get her heart back, which is why it was able to be donated.

“During that period where there was not adequate blood flowing to the brain, there was so much brain injury and brain swelling that her brain suffered an irreversible injury that led to the brain death,” he explained.

Get weekly health news

“Her heart was still healthy. It was still beating. And this is different from patients who primarily have a cardiac arrest from a heart issue, for example.”

Seven of Zeynah’s organs were donated: both kidneys, liver, pancreas, both eyes and her heart. On an emotional level, the heart was the most important to De Groef. Initially, they had been told it would be going to a 27-year-old.

“I joked with my husband that something didn’t feel right and he said ‘We’ve never done this before, none of it feels right.’ And I said, ‘no, no, this specifically,’” she said.

They then learned that the heart was not compatible with that patient. De Groef was worried because it was time-sensitive to find a donor match and there was added difficulty because Zeynah had a rare blood type.

Then they learned that there was a match: a 10-year-old girl.

“Zeynah would’ve been ten that May of 2023 so it just felt really divine that my daughter’s almost 10-year-old heart was going to a 10-year-old girl,” she said, emotion heavy in her voice.

“All I could think of was that she gets to be ten in this weird way. She gets to be ten, and she gets to be 11 and 12, and she gets to live this life… now I feel like there’s parts of her scattered all over that get to do all these different things and experience all these different things.”

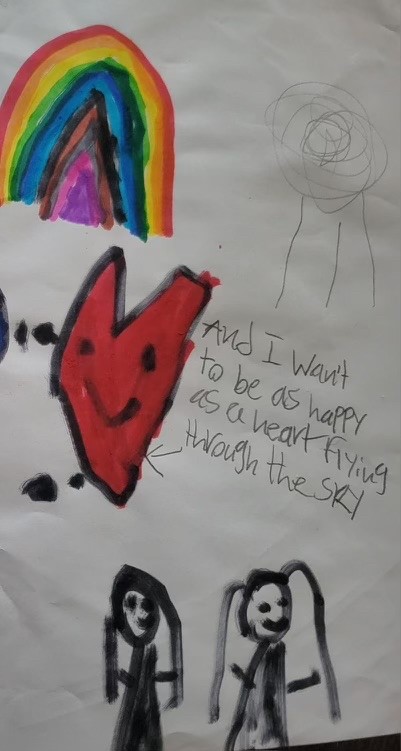

Zeynah also kept a journal and loved to draw. After her death, De Groef found a drawing her daughter had made of a heart with the words “I want to be as happy as a heart flying through the sky.”

“I just thought, ‘how appropriate was that?’ Because I do know her heart went out of the province, I don’t know where,” she said. “There’s been a few (drawings) like that that have really helped to process the grief and the physical loss… that comes with somebody’s passing.”

Ganesan said less than two or three per cent of people who die, even in a hospital setting, end up being a donor simply because of all the moving pieces involved. The organs need to be healthy enough to donate, there needs to be consent to donate and then they need to find a good match.

“That is why I think Zeynah’s story is so unique, because you had this family who was able to be so selfless that they were able to think beyond this disaster, beyond this horrible situation, and think about how she could provide a gift of life to others. And then we were able to support them through that process.”

De Groef is encouraging everyone to register as an organ donor, noting that the chances of becoming one are slim but you could potentially impact multiple lives.

She added that her faith has helped guide her and contrary to what many believe, organ donation is permissible in Islam.

“One of the things that it says in the Holy Quran is that, whoso saves a life, it’s like he saved all of mankind,” she said.

“When we were in ICU and we had this feeling of ‘this can’t be the end for her,’ and then we were given this opportunity to serve a greater good. And I think the ripple effect of the things that you do in this life are so wide. And for her, sometimes I’m lost for words at what she did.”

— with files from Global News’ Ben Harrietha

Comments