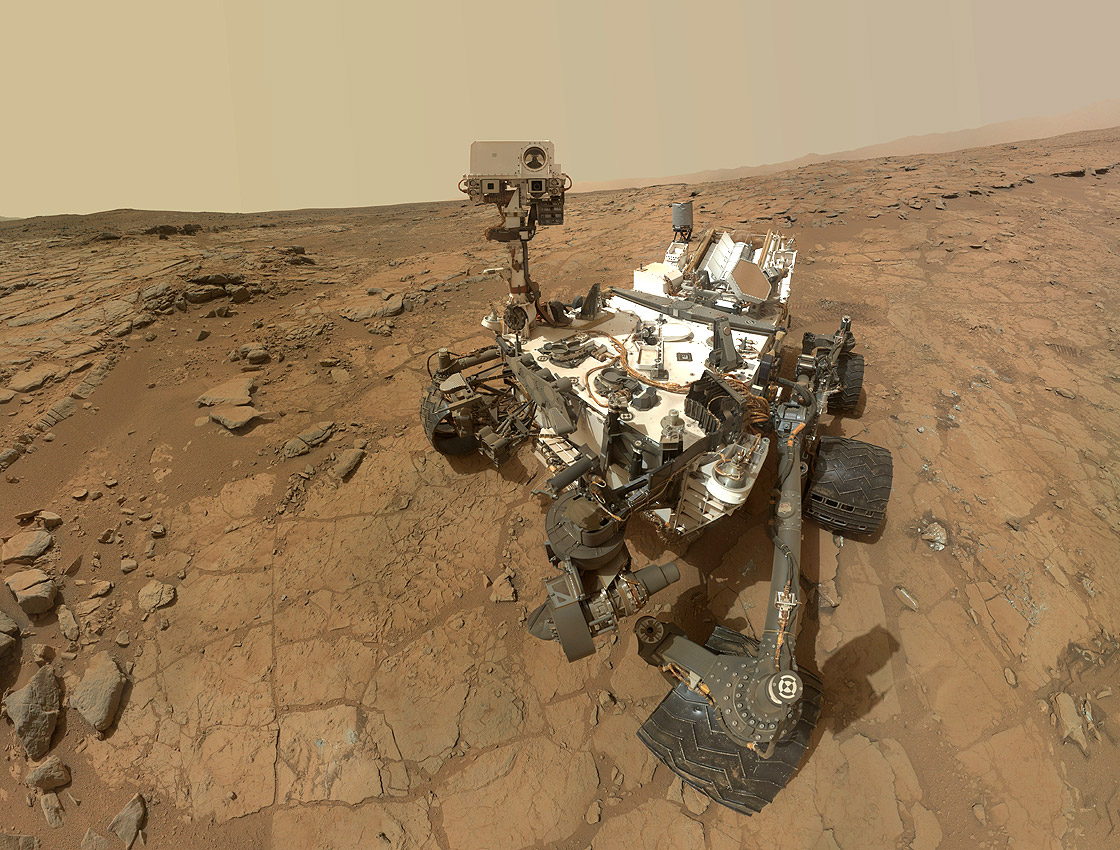

TORONTO – In the television show The Big Bang Theory, Howard Wolowitz, a NASA scientist, often refers to being allowed to drive a “car” on Mars. In fact, in one episode, he crashes a Mars rover while trying to impress a girl.

Though certainly glamorous to be solely responsible for a Mars rover, that’s not exactly reality.

Peter Ilott has “driven” the rover. Ilott, a Canadian working on the current Mars Curiosity mission laughs. “It’s not like there’s a joy stick or anything,” he said.

The reality is that commands are typed into a computer and relayed to the rover. And guess what? If Curiosity thinks you’ve made a mistake, it ignores you until you send it the correct command.

“Seven Minutes of Terror”

It takes a community to build and send a rover to roam the Red Planet. For the Mars Science Laboratory – better known as Curiosity – it took about 750 people, including 450 scientists. And out of that group, only about 20 are Canadians.

One year later, Canadians are still on the job.

Ilott, Lead Telecom Systems Engineer, was one of those 20 Canadians. His job was not an easy one: he was responsible for ensuring that Curiosity could receive commands sent to it. He experienced Curiosity’s “Seven Minutes of Terror” firsthand.

It takes about seven minutes for the rover to slow down from 20,920 km/h to stop on the surface of the planet. It is a complicated and risky manoeuvre compounded by the fact that there is a delay in communication between Earth and Mars.

“We’d practiced these things many, many times, so we’d gone through at least four or five full-blown, end-to-end practices, as though we were doing the real thing,” said Ilott. “A good effect of that is that it feels very familiar. On the day it landed, we all just felt like, yep, we know exactly what this feels like… from that respect we all knew what we had to do… But, of course, you almost put it out of your mind that you’re doing it for real, you just can’t worry about that, you just have to do your job.”

But, of course, they were doing the real thing.

“You kind of build up this tension internally, and it all explodes when you get on the surface, that’s why everybody goes berserk because you can finally let go, you can finally just enjoy it.”

Ilott recalled the excitement of landing on Mars. The rover landed at 1:31 a.m. EDT on Aug. 6.

“It was really cool to see all these young people out there in almost the middle of the night, being all excited and staring at the screen, and this tension,” he said about public viewing events that were held in both Canada and the United States. “We all feel happy that we were able to give the world a good show.”

Richard Leveille, a geologist by training, is a planetary scientist with the Canadian Space Agency (CSA). Though he is currently on exchange at McGill University in Montreal, he continues to work with Curiosity. He, too, was at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) for the landing.

Working at JPL was an experience, recalled Leveille, with so many talented men and women. But, sometimes, the everyday technology could stump even the talented engineers and scientists.

“Adam Steltzner, who was in charge of the landing basically, he took some time off because he had a baby around the landing and so we didn’t really see him, ” Leveille recalled of the days after the landing. “One Sunday evening or late night…it’s quiet at JPL. We have this little photocopy room/kitchen, and so he’s there staring at the photocopy machine, and he turns to me and says, ‘Do you know how this works?’ and I say, ‘Sorry, no.’ And I’m like you just landed Curiosity on Mars and you can’t work this machine!”

Ralf Gellert, from the University of Guelph, is a principle investigator for the alpha-particle-x-ray spectrometer (APXS) instrument on board Curiosity. He had already worked on the same instrument on two previous Mars rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, which reached Mars in 2004. He, too, experienced the “terror” firsthand.

“I had been through this two times with Spirit and Opportunity…but with Curiosity it was more responsibility for me because I was the principle investigator,” Gellert recalled.

“When I first saw the animation of the landing, it scared the hell out of me,” Gellert recalled, laughing.

“It’s really a testament to how great these engineers at JPL work, how they design, how they test, how they make sure that everything works… That’s really a great team down there.”

Living on Mars

Once Curiosity was on the ground, the work continued. And when you’re working on something that’s on Mars, you’re eating and breathing Mars – which means being on Martian time.

Each planet in our solar system rotates on its axis at a different rate. This rotation is responsible for the days and nights. Earth rotates once every 23.934 hours (yes, just under 24 hours). Mars rotates once every 24.623 hours.

So that means the scientists were working about an extra 45 minutes a day. And those 45 minutes a day add up very quickly in a month’s time.

Read more: One year of Curiosity in two minutes

“It was difficult, but it is of course an exciting time, so that really helps you a lot,” Gellert said.

But fortunately, by the beginning of the year, the team was back to Earth time, working in shifts.

Leveille is part of the ChemCam mission. This instrument identifies samples of rock and tells the team the composition of rocks, allowing scientists to choose whether or not they will be further analyzed by other instruments on board.

Life during the first week of the mission was busy, he recalled. And yes, he was on Mars time.

“Five days a week of pretty intensive work,” he said.

And ChemCam continues to keep the team busy. Gellert said that analyzing the composition of Martian rocks helps scientists to better understand the evolution of Mars. His APXS – and the ChemCam – help scientists tell the rocks apart, since being so far away from them makes everything look similar on the Red Planet.

“Every rock looks like every other damned rock,” Gellert said.

Ilott, Leveille and Gellert all agree that the analysis of the Martian rocks will likely far outlast its mission.

There is still a lot of data to go through. “I think things will be coming out in the months and years to come,” said Leveille.

Ilott, who had always wanted to be an astronaut, said that he may have not been able to reach space himself, but it’s nearly as good.

“I always wanted to go into space, but, hey, I helped drive a rover on Mars, so that’s pretty good.”

Comments