It used to be the case that when employers had trouble hiring, wages would increase in places with low jobless rates.

Then came the rise of machines.

These days, employees aren’t being paid much more than they were in the past, a BMO economist said in a report released on Friday.

Coverage of robots on Globalnews.ca:

In a report titled “Wage Against the Machine,” economist Sal Guatieri looked at the effects of robots and automation on wages using data from the U.S. and the OECD.

Hourly compensation per hour in the U.S. grew “smartly” in 2015, he wrote, but since then it has “barely kept pace with inflation.”

Colorado and North Dakota, he noted, have “some of the lowest jobless rates and slowest wage gains in the country.”

READ MORE: These are the jobs that are safe from the robot workplace invasion

Wages could still grow, Guatieri said.

But he went on to say that the national jobless rate only hit 4.3 per cent or less twice in the last 50 years: first, between 1965 and 1970, and second, between 1999 and 2001.

The cost of labour went up in both of these periods.

But now, “new automation is working its way up and down the skills’ chain,” and threatening more jobs than it used to.

Previously, robots threatened jobs in industries such as manufacturing, transportation, office support and retail.

Now, they’re inching into tasks that involve thinking.

Artificial intelligence, he said, can analyze big data and write analytical reports – a skill that’s key in areas such as financial planning, economics and journalism.

And it may not be long before it costs less to have a machine do certain jobs than it would to pay a worker.

A 2015 report titled “The Robotics Revolution” by the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) pegged the hourly cost of a “generic” robotics system in manufacturing at around $28 per hour at the time.

By 2020, just three years from now, that cost could fall to around $20 per hour, which is “below the average human worker’s wage,” the report said.

READ MORE: Here are the Canadian towns and cities that could lose the most jobs to robots

There are, of course, other factors that could be keeping wages from growing — some industries that aren’t as technology-intensive are also seeing modest pay increases.

But “the adverse impact on wages could increase as more tasks are automated,” and labour shortages might “encourage U.S. companies to invest more in technology,” Guatieri wrote.

What the OECD says

The report came two days after the OECD released its 2017 Employment Outlook.

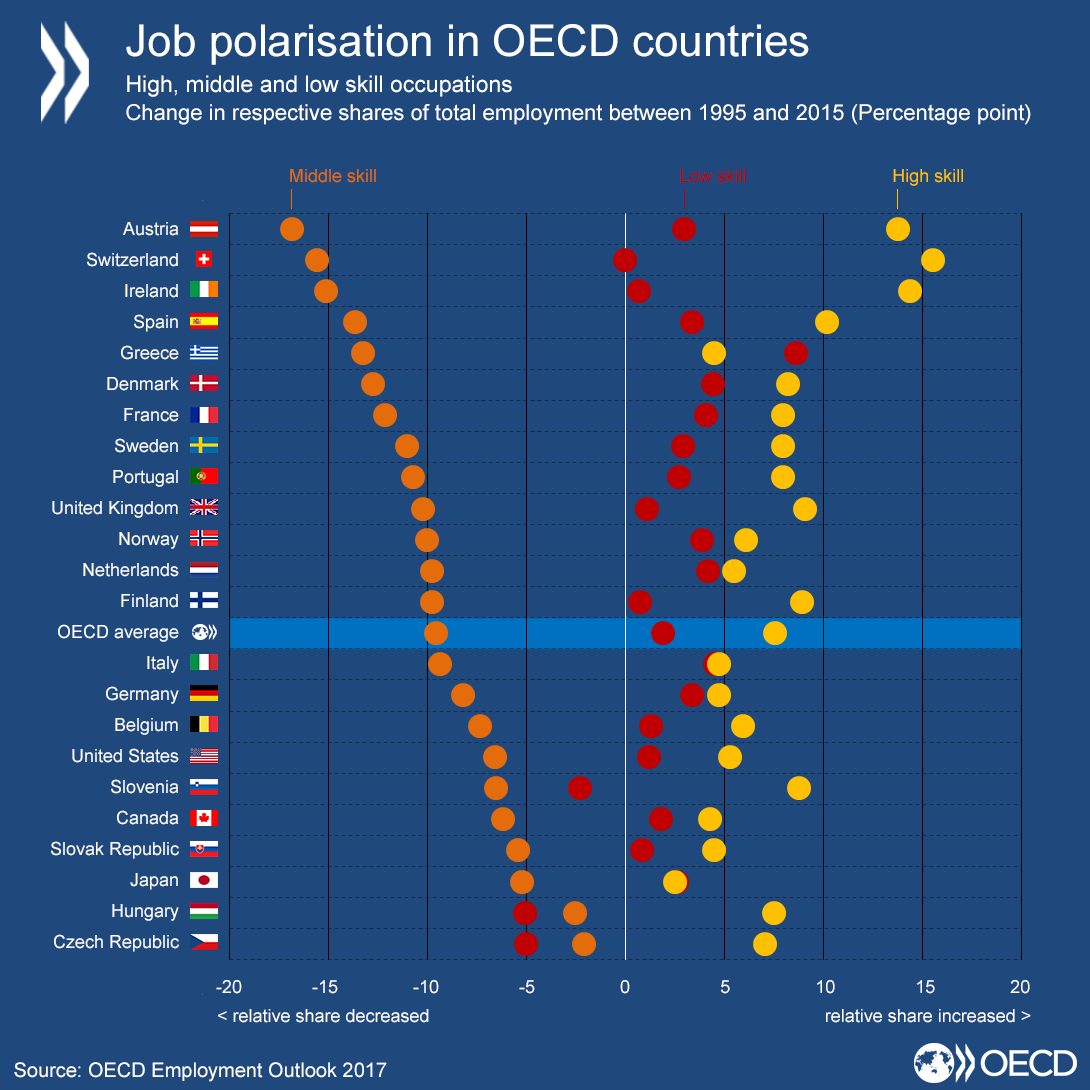

The organization showed that the middle-skilled share of employment in all represented countries fell by 9.5 percentage points between 1995 and 2015, a trend that has been driven by technological changes, it said.

It’s a trend that has led to increasing job polarization, or a larger gulf between middle-skilled, low-skilled and high-skilled occupations.

As middle-skilled jobs have fallen, high-skilled jobs grew by 7.6 percentage points and low-skilled positions grew by 1.9 percentage points in the same time frame.

The polarization is happening because jobs have shifted from manufacturing to service positions, a trend that has seen employees forced to take on lower-paying work.

Canada lost middle-skilled jobs at a slower pace than the OECD average between 1995 and 2015; the only countries where it happened slower were the Czech Republic, Hungary, Japan and the Slovak Republic.

Nevertheless, the quality of employment in Canada has been dropping as job growth has been concentrated in the service sector, according to some analysts.

Comments