TORONTO – We take the sun for granted. Sure, when it’s cloudy for a few days, we may notice and say we miss it. But very few of us know just what the sun is doing.

And it turns out what it’s doing, is slacking off.

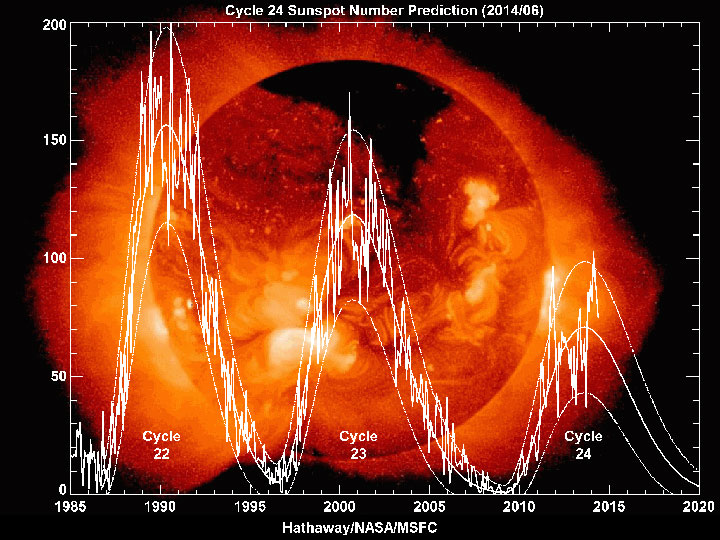

The sun has a cycle that is roughly 11 years. During that time it has a minimum and a maximum. During the minimum, the sun is low in magnetic activity, which means fewer sunspots. Conversely, at maximum many sunspots can dot the surface of the sun.

Right now, astronomers believe that we have reached the maximum of solar cycle 24. Except, our maximum has seen very little activity.

READ MORE: Is solar ‘lull’ affecting global temperatures?

The reason for that? Another solar cycle. This one, a 100-year one.

“We’re returning to behaviour we saw about a hundred years ago,” said Dean Pesnell, project scientist for NASA’s of the Solar Dynamics Observatory.

In fact, the sun was spotless on July 27 – the first time since 1920.

Although we’ve only known about sunspots – cooler places on the sun with complicated magnetic fields – for about 400 years, Pesnell said that the last 80 years have produced the best and most reliable data. However, scientists are still able to chart the history of solar cycles using tree rings, which can go back approximately 10,000 years.

These particles stop in our atmosphere and they change nitrogen by knocking the two nitrogen atoms apart, and convert one of the atoms to a carbon-14 atom. That carbon-14 atom is then taken up by plants which retain that information when it dies.

What astronomers have learned form this is that the sun also has a minimum and maximum that spans a 100-year cycle.

The last big maximum for the 100-year maximum was solar cycle 19, which peaked in the mid- to late-1950s. It was the largest solar cycle we’ve ever seen (this isn’t using the carbon-14 dating).

This would account for the quieter maximum that we’re witnessing.

Asked if astronomers understand what’s responsible for the cycles, Pesnell laughed. “No,” he said.

“We have a pretty good idea that almost all stars that are like the sun have this kind of magnetic stuff going on,” he said. “So it’s not like the sun is really weird.

“As a matter of fact, if the sun is weird it’s because in its class of stars, it’s pretty low in the amount of activity it has.”

But entering this 100-year minimum is an exciting opportunity for astronomers.

Pesnell is quick to point out that just because we’re in a low part of the 100-year cycle, doesn’t mean we’re safe from the sun’s effects. In 2012, spacecraft orbiting the sun recorded the largest solar flare that has ever been recorded. Fortunately, Earth wasn’t in the way, otherwise things could have gotten ugly. When the sun is active, it sends out particles into space at billions of kilometres an hour which can interact with Earth’s magnetic field. They pose a danger to astronauts and can disrupt satellites as well as power grids. In 1989, such an eruption knocked out power to most of Quebec for almost 12 hours.

But there’s no threat of a mini ice age as was last seen in Europe from the mid-1500s to the 1800s. Pesnell said that though the sun could have played a role, there could have been other factors at work that were previously not well known or understood, such as the North Atlantic ocean current that is very important for climate over the United Kingdom.

Comments