- How does FATCA affect me?

- How do I stop my bank from giving my personal info to the IRS?

- How do I get rid of my U.S. citizenship?

- How does all this play out in real life?

Is a second citizenship in the United States an asset? It depends.

Many Canadians have built careers in the U.S. that were simplified by the accident of their birthplace, or of a parent’s. If you want to work in the U.S., it’s useful to not have to worry about visas and green cards. (“Home is the place where, when you go there, they have to let you in,” wrote New England poet Robert Frost.)

But it became a potential liability in February when Canada made a deal with the U.S. on the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, or FATCA.

That obliges Canadian banks to look for “U.S. indicia,” such as a U.S. birthplace, connected to account holders who may be Americans – including Canadian-U.S. dual citizens. They’ll then send the details to the IRS, using the Canadian Revenue Agency as an intermediary. The treaty takes effect July 1.

The prospect has made many people uneasy – enough to have some wondering if this second citizenship is more trouble than it’s worth.

After publishing this story, we’ve been approached by enough accidental Americans who want to become unhyphenated Canadians to see the need for an explainer.

Unlike other industrialized countries, the United States requires its citizens – or others with an American connection, like green card holders – to file tax returns no matter where they live; for non-filers, the system bristles with potential penalties.

“Given that so many non-resident “U.S. persons” will have paid taxes in their home jurisdictions, the vast majority will not owe U.S. taxes after figuring their exemptions and foreign tax credits,” Christians and Cockfield write. “For them, the impact of FATCA is not to increase the amount of tax they pay but rather it is to expose them to onerous fines and penalties for even inadvertent filing and reporting errors.”

There are two aspects to terminating U.S. citizenship: the citizenship side, which is reasonably simple, and the tax side, which isn’t.

This article deals with the citizenship side; you may need professional advice to make decisions about logging out of the U.S. tax system.

READ MORE: More than 3,100 Americans renounced citizenship last year: FBI

How do I stop my bank from giving my personal info to the IRS?

According to the Canada-U.S. agreement, your bank doesn’t need to report you – despite “U.S. indicia” – if you have:

• a certification you are “neither a U.S. citizen nor a U.S. resident for tax purposes” AND

• a Canadian passport or other government-issued proof you have citizenship somewhere other than the U.S.; AND

• a Certificate of Loss of Nationality from the U.S., OR

- a “reasonable explanation” why you don’t have that certificate or why you didn’t become a U.S. citizen at birth, if you were born there.

(Note: Potentially irreversible decisions affecting your citizenship should be based on careful research and professional tax and/or legal advice if you feel you need it.)

| Whom does the U.S. consider American? The U.S. State Department estimates that about a million people in Canada are U.S. citizens under U.S. law. Most of them don’t see it that way: In the 2006 census, about 300,000 people in Canada said they were U.S.-born. Of that number, 160,950 said they were duals, 117,425 said they were Canadian citizens only and 137,425 said they’re U.S. citizens only. So who are Canadian-Americans citizens in Canada, according to U.S. law? – Canadians born in the United States; |

Story continues below map

Interactive: Explore the map below to see where Americans live in Canada. Search using the box above, double-click to zoom and scroll to move around. Click an area for details.

How do I get rid of my U.S. citizenship?

How you lose U.S. citizenship depends on how you came to have it in the first place, how you came to be a citizen of another country and what you’ve done about it in the meantime.

There are two basic ways: renunciation and relinquishment.

1) Renunciation.

Renunciation is much what it sounds like. You make an appointment at a U.S. diplomatic mission, sign a statement acknowledging that you “will become an alien with respect to the United States, subject to all laws and procedures of the United States regarding entry and control of aliens” and swear an oath in front of a consular officer that you “absolutely and entirely renounce … United States nationality together with all rights and privileges and all duties and allegiance and fidelity thereunto pertaining.” (The U.S. flag must be present while this happens.) It costs US$450.

The paperwork is sent off to Washington with a “consular officer’s opinion” about whether you seemed to understand what you were doing or seemed unduly influenced by another person. In most cases, a Certificate of Loss of Nationality eventually arrives from the State Department, backdated to the date you took the oath.

If you then feel it necessary to log out of the U.S. tax system and get a certificate to show your Canadian bank, the IRS requires tax returns to be backfiled for the previous five years, due by June 15 of the year following your renunciation.

2) Relinquishment.

Relinquishment can be more complicated to prove, but can ultimately make things simpler: You essentially need to prove you’ve already done something to lose your U.S. citizenship.

Through the middle of the 20th century, tens of thousands of Americans were stripped of their citizenships for engaging in “expatriating acts” – becoming a citizen of another country or voting in another country’s elections, for example.

Americans who became Canadians ceased to be American by default.

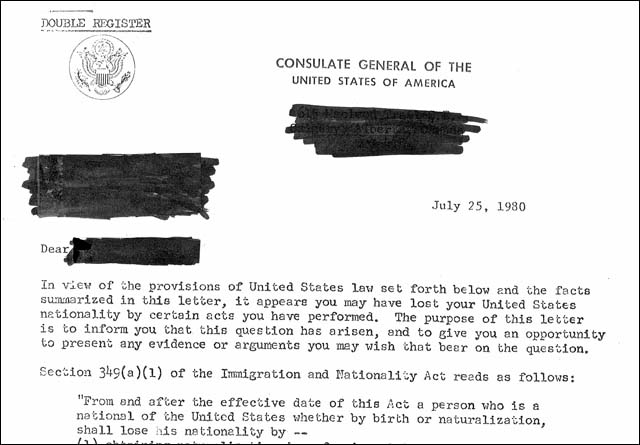

A sample letter sent to an ex-citizen in the period can be seen here.

Isaac Brock Society

A 1980 U.S. Supreme Court decision changed this.

“In establishing loss of citizenship,” the judges wrote, “the Government must prove an intent to surrender United States citizenship.”

Expatriating acts became “potentially” expatriating acts. This meant people who had never wanted to lose their U.S. citizenship could now reclaim it. It also meant “potentially” expatriating acts could be expatriating if you wanted them to be, and if you didn’t do anything afterward to suggest you were still a U.S. citizen.

(Unlike renunciation, the process is free.)

A backdated relinquishment can simplify or eliminate tax reporting requirements; it it was from long enough ago, says California-based international tax lawyer Phil Hodgen, you may be able to escape the paperwork entirely.

Potentially expatriating acts include the following. Remember that in this context Canada is a “foreign state”:

- Being naturalized in a foreign state.

- Declaring allegiance to a foreign state.

- Serving as an officer or non-commissioned officer in the armed forces of a foreign state.

- Working for the government of a foreign state if the person is a citizen of that state or if “an oath, affirmation, or declaration of allegiance is required.”

A U.S. embassy official in Ottawa refused to say whether the statement of allegiance on a Canadian passport application (seen at left) could be potentially expatriating. (U.S. officials would not speak for the record for this story.)

READ: U.S. tax rules for expats too complex to obey, IRS watchdog says

READ: Canadian data doesn’t support stereotype of the wealthy U.S. expat

Story continues below map

U.S. citizens: Maritimes »

So how does all this play out in real life?

We talked to a series of Canadians with some form of U.S. citizenship – by birth or by parentage – who are wondering whether to get rid of it, or already have.

Most of the people we interviewed about their loss of U.S. citizenship, or plans to lose it, asked not to be identified by their full names. Their reasons were: not wanting to be flagged at the border; not wanting a Canadian bank to flag their accounts; abusive calls the last time they were quoted in the media; and “wanting to keep my real and normal life separate from my activity on this matter, so my family and I can move on from it.”

READ MORE: Why are so many American expats giving up citizenship? It’s a taxing issue

Lynne, London, Ont.

When Lynne took the Canadian citizenship oath in 1973, neither Canada nor the United States recognized dual citizenship: By taking on one, she shed the other.

“It had a lot to do with the Vietnam era,” she explains. “The environment in Canada was the complete opposite of the environment in the United States. In the United States, young people were furious at their government and hated Nixon. In Montreal, people were still on a high from Expo ’67.”

‘I don’t know how any Canadian bank could refuse to accept that.’

“When I became a Canadian citizen, I phoned the U.S. consulate to see how it would affect my U.S. citizenship, and I was told clearly, firmly and directly that I was permanently and irrevocably relinquishing my U.S. citizenship. I was told there was no turning back, I was told to think very carefully, because this decision was not reversible, that I was young –I was 22 at the time – and that there was a very good possibility that I would change my mind.”

If her bank asks about her American birthplace, Lynne plans to produce the oath she swore in 1973 as proof she’s no longer American.

“I don’t know how any Canadian bank could refuse to accept that.”

Vi, Manitoba

Vi successfully relinquished her U.S. citizenship in 2013 based on a job she had had at Manitoba Health in the mid-1990s, which turned out to qualify as “the government of a foreign state.”

She was born in Kansas, where her father worked as a minister, and returned to Canada at age 6. When U.S. border guards started telling her, about six years ago, to cross the border using a U.S. passport, “the question started arising around whether there’s something that needs to be done.”

‘I didn’t want to be an American.’

“I really had no interest in entering the U.S. tax system, because I didn’t have a Social Security number, had never worked there, had never earned any money there, hadn’t lived there for most of my life, and certainly didn’t want to begin with that kind of filing.

“I didn’t want to be an American,” she explains. “I had no need to live there again.”

But she had to talk an unwilling consular officer in Calgary into sending her paperwork to the State Department.

“He just said that ‘None of this can really cut it – I won’t be recommending this as a relinquishment.’ I just said to him: ‘Please send my stuff off to Washington and see what they say.’ I was pretty sure that it wouldn’t work out.”

After a year and a half, a Certificate of Loss of Nationality arrived, backdated to December of 1994, when she took the job.

Carol Tapanila, Calgary

U.S.-born Carol Tapanila, who immigrated to Canada in 1969 and became a citizen in 1975, wasn’t able to relinquish (she renounced instead, in 2012) when she was told in 2011 that she should be filing U.S. tax returns.

“I made mistakes,” she reflects.

(U.S. citizens are required to enter the country on a U.S. passport, and a U.S. birthplace on a Canadian passport is hard to hide. They’ll often be told at the border to start using a U.S. passport, but doing so undermines an argument that U.S. citizenship has been lost. It also loops the passport applicant into the U.S. tax system.)

In 2008, she gave in and started using a U.S. passport. Tapanila also voted in the 2008 U.S. presidential election which, she said, “sealed my fate.”

‘A good portion of these one million U.S. citizens in Canada … like my son, they are entrapped.’

Tapanila is worried about her Alberta-born, developmentally disabled son, who as a dual citizen theoretically has U.S. tax-reporting obligations. The U.S. consulate in Calgary ruled that he doesn’t have a level of understanding of citizenship sufficient for him to renounce, and Tapanila isn’t allowed to do it on his behalf. At 70, she’s concerned about changes that may affect him in the future – even though it’s conceivable he could fly under the radar indefinitely.

In the end, she says, tax filings for her, her husband, her daughter and specialized legal advice about her son’s situation cost $42,000.

“There are going to be a good portion of these one million U.S. citizens in Canada who are going to be affected with things like disability, or dementia, where, like my son, they are entrapped.”

Kathleen, Ottawa

Perversely, it can be harder for people born in the U.S. to Canadian parents and brought here as children to lose U.S. citizenship than for Americans who, as adults, became naturalized Canadian citizens. If you’ve always been Canadian, you don’t have an expatriating act to point to.

Kathleen wants to shed the U.S. citizenship she acquired at birth (her father was working in Texas; she came back to Canada as a baby and has lived here ever since) but wants to avoid the tax-reporting complications of renouncing.

‘It’s random, and it’s ridiculous’

At this point, she’s “still waffling” about how to proceed.

“People who left as adults can come to Canada as Americans, acquire Canadian citizenship and because they’ve given that oath they can get a backdated CLN. Whereas myself, who was born Canadian, with Canadian parents, all my history is Canadian, I can’t do that. I’m stuck. It’s random, and it’s ridiculous.”

Comments