This summer’s record-breaking heat is sparking a burning question: How hot is too hot for the human body?

Dr. Stephen Cheung has been studying that question for 25 years. Cheung runs the Environmental Ergonomics Lab at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ontario, where he’s measured the physiological impact of extreme temperatures on firefighters, soldiers, professional athletes and, on this occasion, a journalist.

I visited Cheung’s lab on a muggy August morning, but the temperature outside was nothing compared to what I was about to experience. The walls of the lab were lined with exercise bikes, oxygen tanks and computers. There was a large immersive tub full of water, with a cheeky ‘Beware of Sharks’ sign tapped to the front.

I was directed towards the far corner of the room to a bathroom-sized air-tight environmental chamber, where Cheung’s team can control the flow of oxygen, temperature and humidity.

Cheung explained that I would spend two hours inside the chamber: the first hour with high dry heat and the second hour with high humidity.

“Heat is bad, but it’s really the humidity that makes things so much more challenging for a body,” Cheung said.

Studies have found humidity is rising even faster than global temperatures, as warming seas and land surfaces see more water evaporate into the atmosphere.

“Unfortunately, it is becoming much more of a reality for us, even in a relatively cold country like Canada,” Cheung said.

Before entering the chamber, I was instructed to swallow a pill thermometer to record my internal temperature. Next, I stepped on a scale to check my weight and then Cheung’s colleague, Phillip Wallace, spent 10 minutes attaching about a dozen sensors to my chest and legs to measure my skin temperature and heart rate.

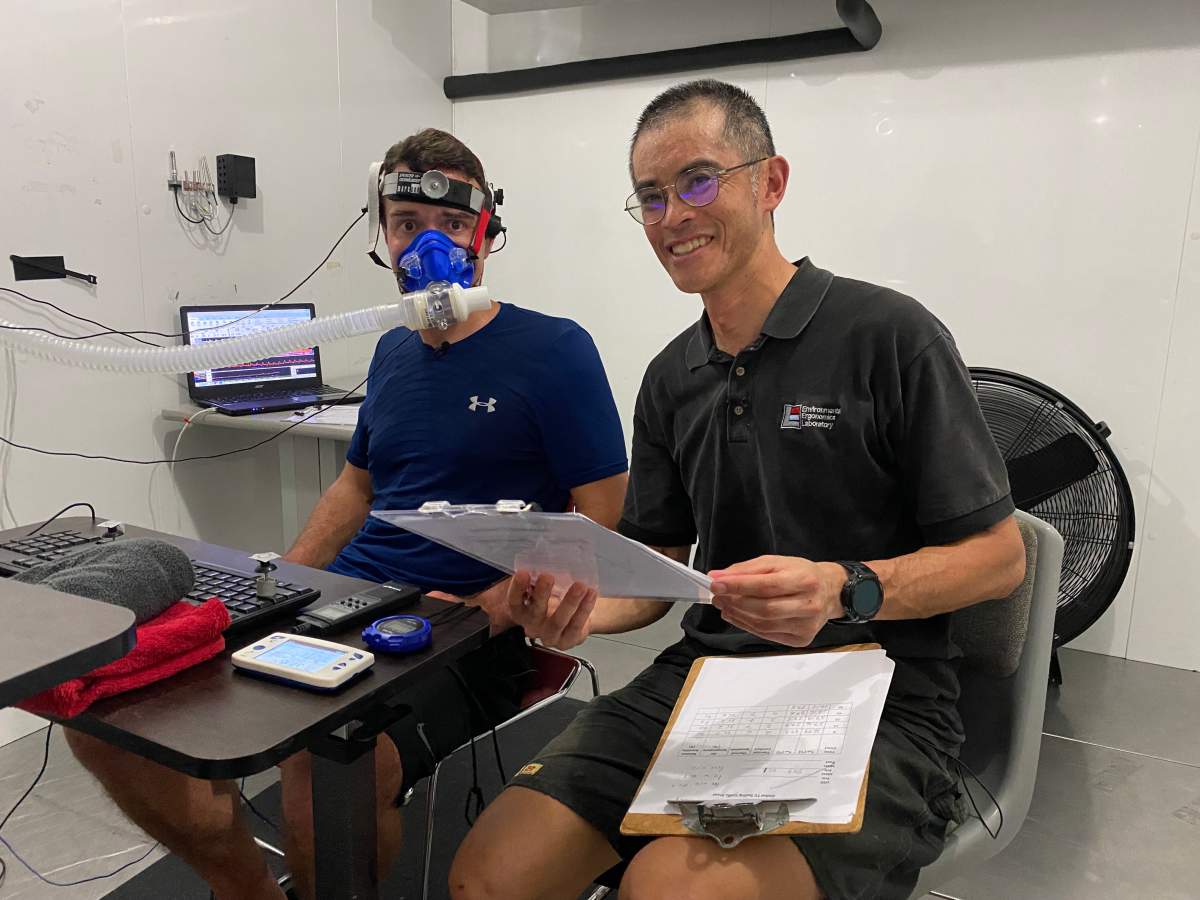

I then entered the chamber and sat-down at a small computer desk. Wallace placed an oxygen mask on my face and a plastic crown on my head, to track my breathing and the flow of blood to the brain.

Get weekly health news

“When you’re out in the sun and out in the heat, it’s not just your body physically being challenged, but it’s also your brain being mentally challenged too,” Cheung explained.

To measure my cognitive function, I was given a memory test: A series of playing cards appeared on the computer screen and I was then asked to recall them. The researchers recorded my baseline score, shut the chamber door and cranked the heat.

I sat and waited. After one hour at 35 degrees Celsius with 30 per cent humidity, I was feeling warm but still comfortable. My heart rate, internal and skin temperatures had barely changed. The sweat towel Cheung had provided sat on the desk unused. I was given another memory test and I scored even higher than the first baseline test.

I was then instructed to take a cold shower and an hour-long break for lunch. Upon my return, I went back into the chamber. They turned the heat up once again to 35 degrees. But this time they add a dangerous ingredient: humidity.

“You’re going to feel just perceptually a lot more uncomfortable. It’s going to be a sweat fest,” Cheung laughed.

In dry heat, sweat evaporates into the air, which moves heat away from the body and cools the person down, he explained. But not in humid heat.

“The sweat that you’re producing just cannot evaporate into the environment because the air is already so filled with water vapour,” he said.

After about one hour inside the chamber with about 80 per cent humidity, I was soaked in sweat, feeling nauseous and light-headed.

My internal temperature went up 0.3 degrees and my skin temperature climbed seven degrees. I lost 0.3kg (0.7 lbs) in water weight and my heart rate jumped by more than 10 bpm (beats per minute), even though I was seated and barely moving.

“Your heart is pumping a lot of blood out to the skin to get rid of the heat,” Cheung explained.

“And so the heart has to work a lot harder. It has to pump stronger and more frequently to move blood around your body. And that can be a big problem, whether you’re just resting and especially when you’re exercising.”

I then performed another memory test. I had to work harder to focus on remembering the cards on the computer screen, as sweat dripped down my brow stinging my eyes. I thought I’d performed reasonably well, and was surprised to learn that I had made twice as many errors compared with my previous test.

“Your blood flow going to the brain gets reduced and so that can obviously alter how your brain works,” Cheung said.

“You’re hot and bothered, you can’t think straight, you may also not be paying attention to the environment. So that’s also when accidents can happen.”

As temperatures rise, Cheung urges Canadians to pay closer attention to the humidity, including metrics such as the humidex or the ‘wet-bulb’ temperature, which combine temperature and humidity into one value.

For those without air conditioning on hot and humid days, he suggested having a cold shower or using a fan to keep cool. Fans are particularly effective in humid heat, assuming the external temperature is colder than one’s body temperature, as is usually the case in the Canadian climate.

Comments