GRAPHIC WARNING: This article contains details some readers might find disturbing.

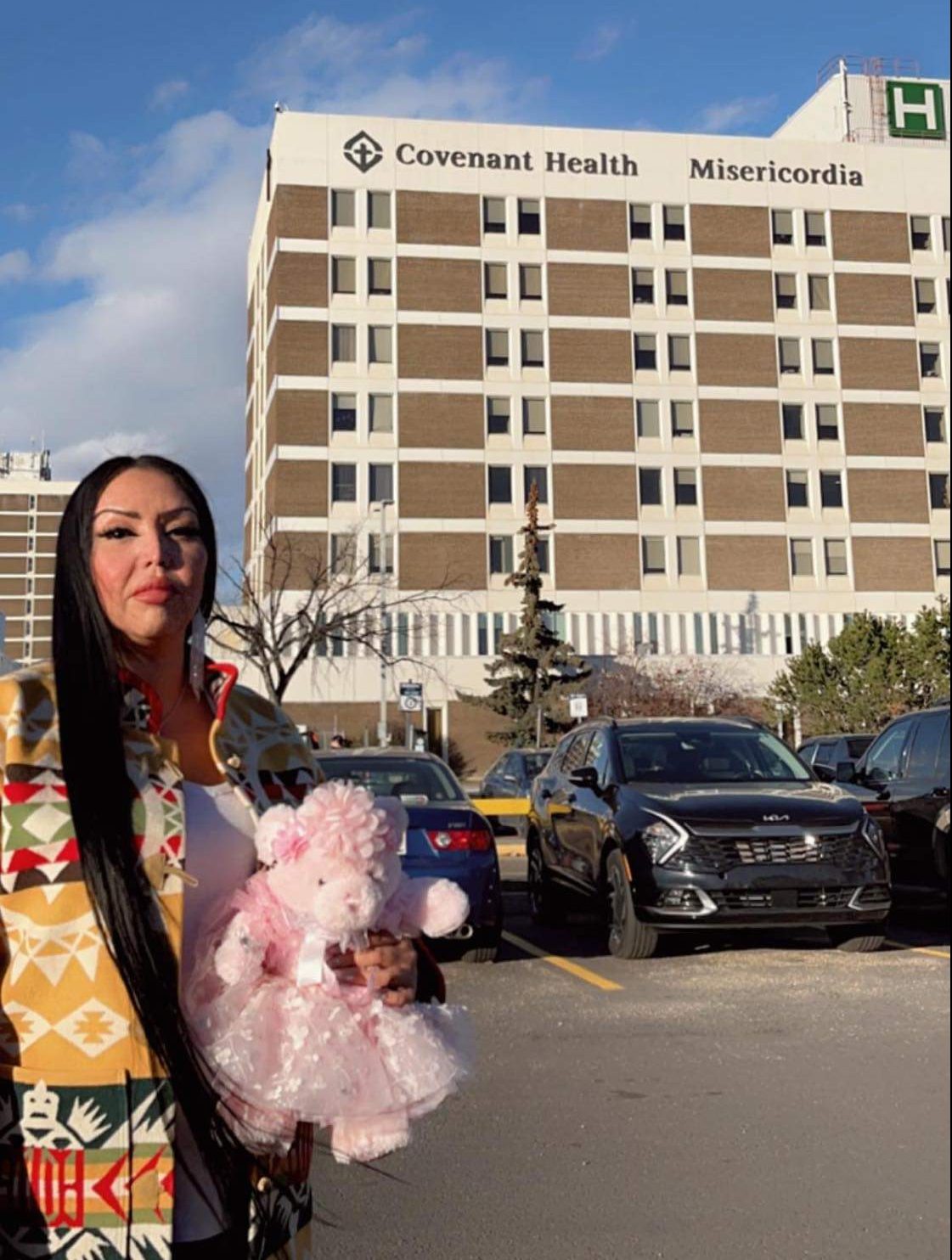

Pearl Gambler battled through emotion as she spoke about her experience of allegedly being left alone and screaming for help during the premature delivery of her late daughter at the Misericordia Hospital in Edmonton in June 2020.

Gambler, a member of the Bigstone Cree First Nation, shared her traumatic experience with reporters on Thursday. She was joined by her lawyer Shelagh McGregor and Treaty 8 First Nations of Alberta Grand Chief Arthur Noskey.

They say the treatment Gambler received was inhumane and points to the racism that still exists in Alberta healthcare.

Her lawyer said a lawsuit has since been filed, complaints made to professional medical bodies, and a human rights complaint also submitted.

McGregor said Gambler decided to share her story “for the express purpose” of ensuring changes are made so that Indigenous people are treated fairly and respectfully in the health care system.

“The events that happened here would not have happened to me as a Caucasian woman,” the lawyer said. “There’s a lack of humanity in her treatment.”

In a statement to Global News, Covenant Health said it is reviewing the allegations.

“Covenant Health takes any and all complaints and concerns seriously, including allegations of racism and discrimination. Racism and discrimination in all forms have no place within Covenant Health.

“Due to privacy legislation, we are unable to provide further commentary on or discuss any specific patient information.”

Gambler said she was just over 19 weeks gestation with her third child when she had severe lower back pain and went to see her obstetrician in Edmonton on June 10.

An ultrasound done on June 3 “showed no abnormalities,” Gambler’s lawyer said. The baby’s due date was Nov. 1.

Gambler said she returned to her doctor on June 11, was examined, and told to go to the Misericordia Hospital, where a bed in the maternity ward would be waiting for her. Her doctor mentioned a possible cervical stitch to prolong the pregnancy, Gambler recalled.

When she and her partner arrived at the hospital, she was put in a wheelchair and taken by a nurse from the emergency room to the maternity ward, Gambler said.

She said a woman at a desk in the maternity ward “jumped up and said: ‘What are you here for?’

“I had my hair in two Dutch braids and I was wearing this same shirt that says: ‘Strong, resilient, Indigenous.’

“She looked at me up and down and she said: ‘There’s nothing here for you.'”

Gambler recalled being taken back to the emergency department for several hours, then later moved to a room with three other patients, having an ultrasound done, before being taken to her own room on the fifth floor. Nurses checked on her throughout the night, monitoring the fetal heartrate and ensuring she wasn’t contracting.

On the morning of June 12, Gambler said she spoke with two physicians who told her they didn’t want to conduct an exam or attempt a cervical stitch for fear it would disrupt her cervix and might increase contractions.

Get weekly health news

Shortly after, Gambler said her obstetrician came in with a male nurse and told her they needed to “check” her. Gambler said no several times before consenting.

“I let her check me and she hurt me so bad. And she just walked out. She didn’t say nothing. I was in pain and could just feel like burning and then my contractions started to come.”

Gambler said she kept asking for help from hospital staff, told them the baby was coming, and she was told by staff that they’d go get a nurse or a doctor.

“Nobody came,” she said.

Once her contractions started coming back to back, her partner ran out of the room to get help. The male nurse who attended her exam earlier that morning returned as she was delivering her baby.

“He stood 10 feet away from me and he watched me deliver my daughter and he didn’t help me. He put his hand over his mouth and he watched me deliver and I was screaming,” Gambler said. “I could feel my daughter moving.”

She said she kept pressing the call button for the nurses and was screaming for help. She said she “snapped” at the male nurse and he ran out to get a doctor.

“I knew she needed help. There was nothing there for her in that room. She was moving and moving and then she’d stop and then I would think she’s gone and then she’d start moving again and I’d start screaming. And I was hitting the buzzer and nobody came. Nobody came.

“My partner was beside me and we were crying. It was horrible. We were crying.”

About 20 minutes later, Gambler said several nurses came into the room.

“The nurse asked him to cut the umbilical cord but we were holding each other and then she cut the umbilical cord… She asked me if I wanted to hold her. I started to let go of my partner to reach for my baby and she told me my baby was gone.”

Gambler said the nurses took the baby away but that medical records show the infant was still alive 32 minutes after she was delivered.

Gambler said her friend saw the baby in a basket on a shelf at the nursing station.

“My baby was still gasping for air… It’s in the medical records that she was still alive. When they took her and they told me she was gone, she wasn’t gone.”

Gambler said her placenta didn’t deliver spontaneously so she was put on oxytocin and contracted for almost six more hours.

“They gave me needle after needle after needle. They gave me something to start my labour again and then they left me like that for hours until about the sixth hour, I was starting to feel faint, I was starting to feel dizzy, I knew something was wrong. The male nurse insisted I go use the bathroom to see if I had passed my placenta. I filled two of those pads with blood clots and I told him there’s something wrong. He kept on telling me to go back to my bed.”

The nurse went to get a doctor, who saw the blood and ordered surgery, Gambler said.

As they were preparing her for surgery, Gambler said heard someone ask: “Will you be taking your specimen home?”

“You mean my baby?” she replied. “My baby is coming home with me. She will have a proper burial.”

When that person offered cremation at the hospital, Gambler said she yelled at her to get out of the room.

“They prepped me for surgery, I had my placenta taken out, then I had to prepare a funeral for my daughter,” she said.

Gambler said she received the medical records six months after her daughter’s funeral.

“I knew everything was wrong, what happened in that hospital.”

Gambler and her partner named their late daughter Sakihitowin Azaya Gambler, which means “loved” in Cree.

A statement of claim, filed Oct. 12, 2022, lists Gambler’s obstetrician (whose name is redacted) as well as Covenant Health as defendants in a lawsuit.

The statement of claim alleges the defendants breached their duties by, in part:

- Failing to provide appropriate medical care in treatment Gambler’s pre-term labour

- Failing to ensure there was proper assessment and monitoring of the mother and fetus

- Failing to manage the delivery

- Failing to advise various options for treatment

- Demonstrating a complete lack of care or treatment for Gambler’s baby after she was born alive

The statement of claim alleges the defendants did not provide Gambler and Sakihitowin adequate medical care “in part or in whole due to Gamblin’s race.”

The lawsuit is seeking $1.38 million in damages.

The allegations have not been proven in court.

Global News asked but Covenant Health did not say if a statement of defense has been filed. Gambler’s lawyer said she doesn’t have one.

Calls for change

“Indigenous lives continue to be less important in Alberta’s healthcare system,” said Grand Chief Noskey at Thursday’s news conference.

“This has to change, and I am asking Alberta’s new premier to work with us to make this change.”

Treaty 8 is demanding the following immediate actions:

- Full implementation of the health recommendations of the 94 Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

- Public inquiry into the adverse health effects for Indigenous people in Alberta, including systematic anti-Indigenous discrimination in the healthcare system

- Hospital-wide review of systemic anti-Indigenous discrimination at Misericordia Community Hospital

- Implementation of increased and regular Indigenous cultural training across Alberta healthcare system

- Ongoing measurements and annual public reporting by province on Indigenous equity in health care system, including individual reports from each hospital

- Expanded network of independent Indigenous patient advocates to ensure adequate coverage at every hospital

- Increased funding for Indigenous-led, Indigenous-focused healthcare programs and facilities

- Province-led consultations with Indigenous people and communities to develop and implement further recommendations to improve health outcomes

- Those responsible for what happened to Pearl, Sakihitowin and their family to be held accountable.

“Because a lawsuit has been filed, we’re not going to comment on any correspondence with Covenant Health,” Gambler’s lawyer said.

Alberta Health Services said it “takes action against individual and systemic acts of racism and discrimination whenever we are made aware of them.

“We know many Indigenous peoples do not seek care for an illness or injury because they do not feel safe or welcome within the health system, or that they believe their cultural traditions will not be respected or understood.”

In response, AHS has taken steps to improve care, including hiring Indigenous liaisons in all zones, Elder advisors, and developing the Indigenous Health Commitments roadmap.

“We will bring recommendations and next steps to the Indigenous anti-racism working group once it is established,” AHS spokesperson Kerry Williamson said in a statement.

“AHS has taken significant steps to address discrimination and intolerance in recent years, and this work is ongoing. This includes the creation of several workforce resource groups to bring together voluntary members of the workforce who share a common identity or background, and mandatory cultural awareness training for leaders and staff. In addition, we have a number of diversity and inclusion education, including unconscious bias and allyship webinars. All staff are also required to complete mandatory Indigenous awareness and sensitivity training as part of their employment with AHS.”

Comments