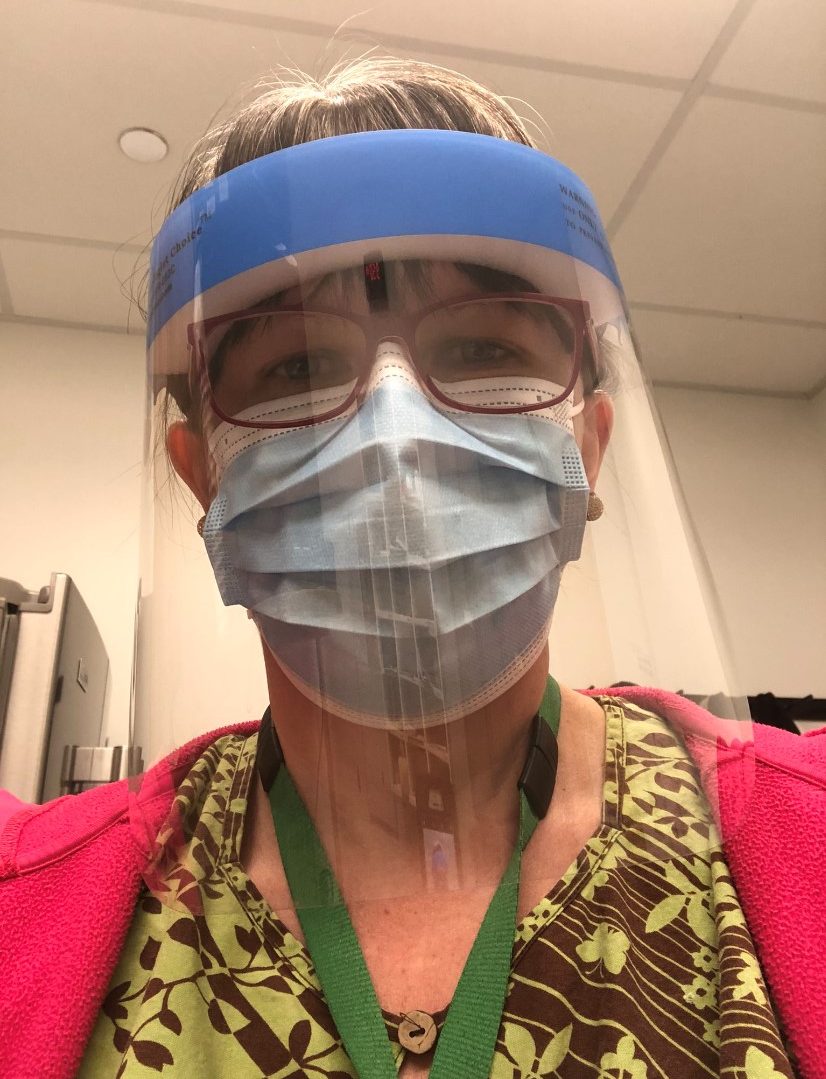

Yvonne Sawatzky is exhausted.

She’s a psychiatric nurse working in a long-term care facility who recently worked 10 12-hour shifts in 13 days.

That span only involves picking a few additional shifts, but it weighs on her after working through the pandemic for so long, especially in a rural area.

“Quite often we were so short that we didn’t have a second nurse, so I had no (licensed practical nurse),” she said,

“So I was the only (nurse) for 30 people.”

She said the lack of staffing is especially bad because she works in a rural area — Cut Knife, Sask., a town of about 600 people roughly 50 km east of North Battleford.

The entire medical staff at the facility consists of about seven people.

That means one or two people from that team needing to isolate with COVID-19 puts everyone back in the overtime situation.

Get breaking National news

Speaking to Global News a few days after the stretch of shifts, Sawatzky said she is feeling better.

But she said she noticed an effect it had on her.

“I do know that my stamina and my energy levels are not much up to par. It did physically drain me to spend that much time there. And I love my job,” she said.

She’s only worked at the care facility full-time for a few months, having worked in the Saskatchewan Hospital in North Battleford for 20 years.

Perhaps that contributes to her view when she said the pandemic seemed inescapable, from many people believing it is comparable to the cold and flu — which she said felt like gaslighting to hear — to having her immunocompromised husband catch it.

He has recovered fully, but each event adds to the strain.

And the strain has been considerable. Recent waves drew attention towards ICUs and testing, but earlier strains of COVID-19 swept through long-term care facilities with deadly, tragic results.

And as of Monday, a Saskatchewan government website listed COVID-19 outbreaks at more than 60 separate long-term or personal care facilities.

Saskatchewan Union of Nurses president Tracy Zambory said the pandemic made rural staffing, which was already precarious, worse.

“They’ve been dried up for quite some time when it comes to any sort of recruitment and retention that could happen to be able to manage through the crisis,” she said.

The Saskatchewan government dedicated around $6 million towards hiring more than 100 long-term care aides over several years. In the 2022-23 the government set about $1.5 million aside to bring healthcare workers from the Philippines to Saskatchewan.

Zambory said she hasn’t heard of any new aides yet and said bringing foreign workers into the healthcare system and fully integrating them takes time.

Global News contacted the office of Health Minister Paul Merriman for comment but didn’t hear back by deadline.

Zambory said the province is facing a human resource crisis when it comes to the health-care system.

“We have got to do something and we’ve got to do something pretty quick,” she said.

Sawatzky said she worries about staffing levels, the overburdened hospital system, and what both mean for patients.

She said she’s thought about leaving the profession, even though she loves her job.

She said she’d consider working another 10 years, but she knows she can retire in six.

“I would stay longer if I didn’t feel like. I had. Potentially to show up there eight days a week,” she said.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.