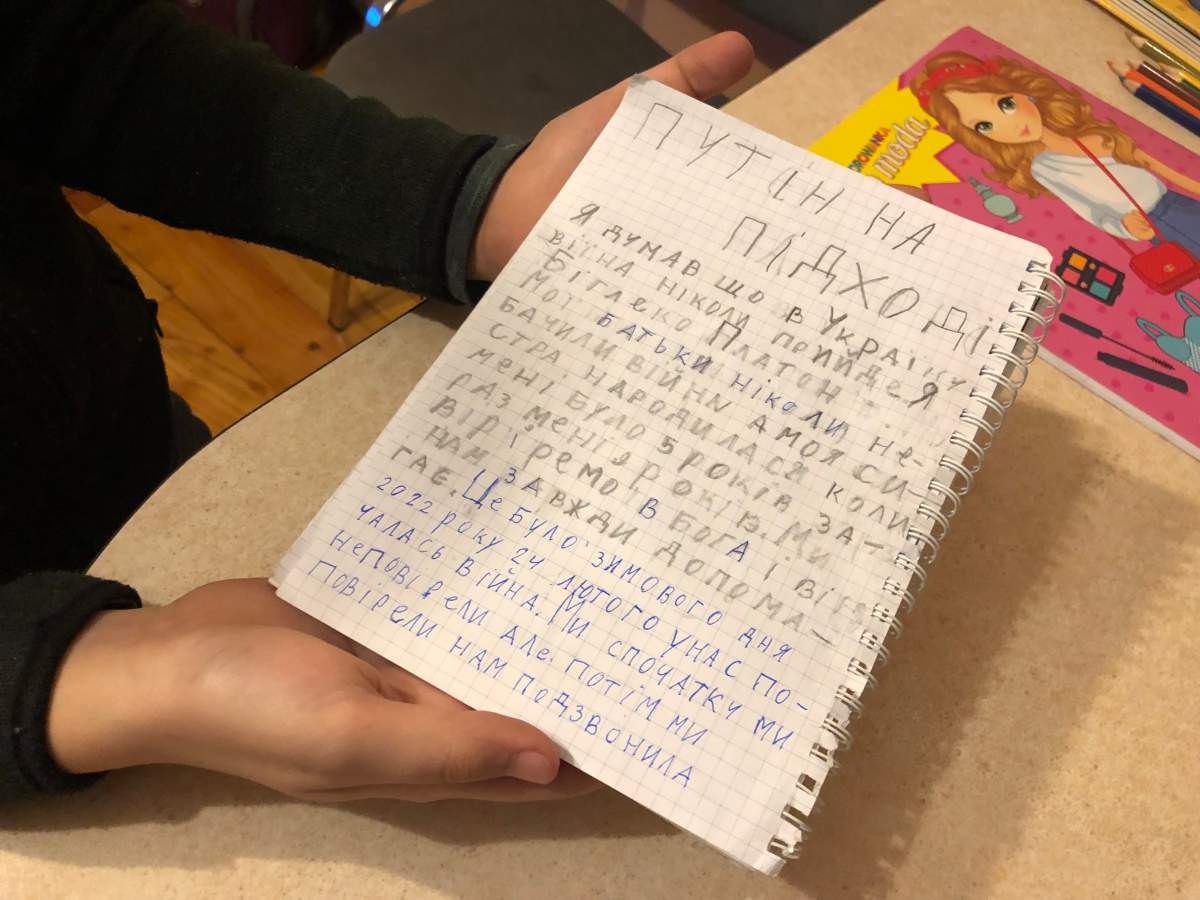

His feet barely touching the ground, nine-year-old Platon Bihlenko sat at the kitchen table inside an apartment in Poland, reading aloud the story he had composed.

Written in neat, boxy letters, it was about a family that never imagined how war would touch their lives — until the Russians began shelling their city in southern Ukraine.

“Putin is coming,” he read.

A Grade 3 student at School No. 57 in Kherson, Platon fled Ukraine on foot on Tuesday, along with his mother Natalia and his little sister Maria, who does gymnastics.

After they crossed the border into southeast Poland, a volunteer picked them up and brought them to an apartment in the nearby city of Rzeszow.

The woman who took them in was a Ukrainian-Canadian named Heidi Baumbach, a violinist who ran a music school in Alberta.

She was so moved by the news from Ukraine that she renewed her passport and flew to Poland to help, even if she wasn’t sure how.

In Warsaw, she met a volunteer who asked if she would help house refugee families arriving from Ukraine, so she rented an apartment on Airbnb.

“It’s just what everyone is doing over here,” she said.

The number of refugees who have fled President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has reached one million, the United Nations refugee agency said Thursday, calling it Europe’s worst refugee crisis since the Balkan wars.

In Poland alone, almost 475,000 “fleeing war” have arrived since Feb. 24, the country’s interior ministry said.

“This is an illegal, unjustifiable, unconscionable war, and Putin will have to pay for this,” Foreign Minister Melanie Joly said during a visit to Rzeszow on Wednesday.

She said international sanctions were beginning to bite in Moscow, noting the Russian ruble had tumbled in value. “Clearly, the Russian economy is affected by this.”

But Putin’s expansionist war, which aims to topple the government in Kyiv and absorb Ukraine into Russia’s orbit, has already broken up families like the Bihlenkos.

Get daily National news

Natalia Bihlenko, 34, and her husband Oleksiy, 37, are driving instructors at a company called Traffic Light. They have been married 13 years and lived on the fourth floor of an apartment in Kherson, a city of about 280,000 on the Black Sea.

They went to church on Sundays and helped organize summer camps for orphans. Their five-year-old daughter was in kindergarten, and Platon liked swimming.

When the Russian forces began amassing on Ukraine’s borders, they watched the news like everyone else, but couldn’t bring themselves to believe they should worry.

On the first day of the Russian attack, Bihlenko’s mother phoned at 6 a.m. and told them to leave the city, but they dismissed the doom-saying as “TV stuff.”

But then her mother said Russian tanks were already around her city, Nowa Kachowka, just an hour’s drive away up the Dnieper River, and Bihlenko began to pack.

When the shelling of Kherson started, the Bihlenkos took cover in the basement of their building, reassuring the children it was just a game.

Three days into the barrage, Bihlenko’s husband said he couldn’t protect them anymore and they were going to have to make an escape. Last Saturday, they packed two changes of clothes and left in their Nissan X-Trail.

It took a day’s driving to reach the long line of vehicles waiting to cross into Poland. The queue stretched for tens of kilometres, Natalia said.

The sun went down. It got cold. They came to a school and the locals let them sleep inside. In the morning, the locals bussed them to the border so they could cross on foot.

Bihlenko’s husband stayed behind. The government has ordered Ukrainian men not to leave the country in case they are needed to fight. Kherson appeared to have fallen to the Russian forces on Thursday, the first city to be captured during the invasion.

Sitting with two other refugee families in the small apartment that has become their temporary shelter, Bihlenko, said her husband had been helping other families flee, driving women and children to the Polish border.

“He’s brave,” she said.

It was hard to leave him, she added. She said he asked her to be strong and not to show her fear to the kids, but she couldn’t help tearing up. She was worried she might never see him again. She didn’t want Maria and Platon to grow up without their father.

As she wept, Platon stroked her hair to comfort her.

She believed Putin had united Ukrainians, and said the world needed to help the refugees and send military aid, or he might keep going, into Poland and beyond.

“I thought that war would not happen in Ukraine,” her son said, reading from his spiral-bound notebook.

“I am Platon. My parents never saw war and my sister was born when I was five.”

He said the story was not finished yet.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.