By Krysia Collyer

Global News

Published February 12, 2022

6 min read

“Antimicrobial resistance is a pandemic already,” said Strathdee, who is the associate dean of global health sciences at the University of California, San Diego. “It’s an epidemic that exists on every continent. It’s out of control.”

A recent study published in the Lancet found that more than 1.2 million people were killed in 2019 by antibiotic-resistant superbugs.

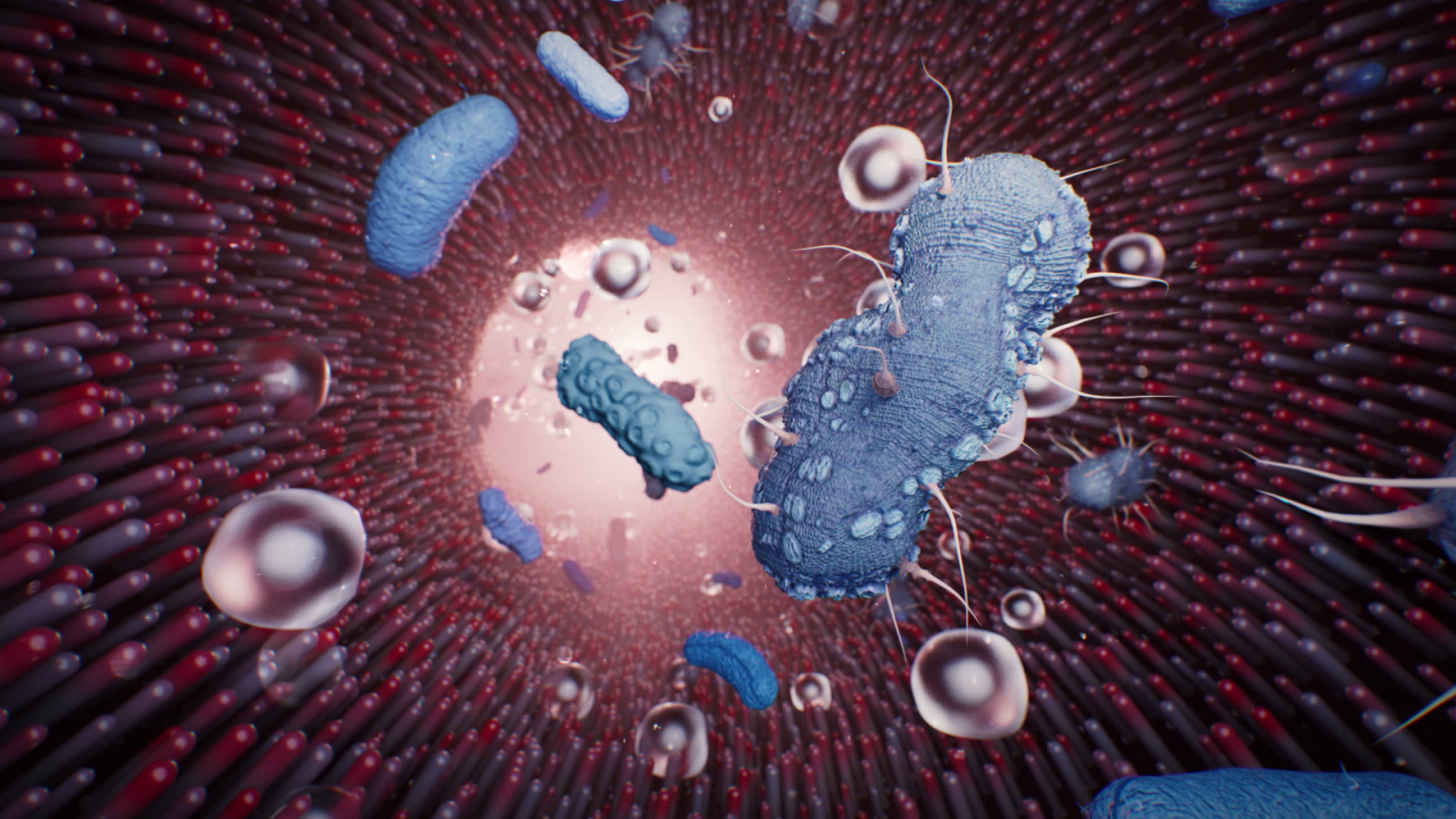

Antimicrobial resistance or AMR occurs when micro-organisms become increasingly resistant against many treatments used to cure infections, including antibiotics.

By 2050, it’s projected that 10 million people every year will die of drug-resistance infections.

Strathdee and other experts believe that figure is outdated and in reality, is far higher because of COVID-19.

“It’s worsening under COVID because resources have been directed away from antibiotic stewardship in hospitals,” she told Global’s The New Reality.

Another potential reason for the increase of AMR is the misuse or overuse of antibiotics to fight COVID.

According to a report by the Pan America Health Organization (PAHO), more than 90 per cent of patients admitted to the hospital for COVID in the Americas were prescribed an antimicrobial, but only seven per cent need them.

She said there are a number of things that have happened through the COVID-19 pandemic that could cause antimicrobial resistance to increase, including the reallocation of resources away from surveillance and prevention to deal with the immediate emergency.

“There have been a couple of studies that have come out more recently that have shown that health-care acquired infections, but also antibiotic-resistant organisms in hospital settings, have been on the rise through this pandemic,” Dr. Hota told Global News.

Facilities in the U.S. and Europe have reported increased cases of superbugs among patients hospitalized with COVID, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“There’s also COVID patients who are been on ventilators who are exposed to different bacteria in the hospital,” Strathdee said.

“I mean, can you imagine being on a ventilator, living through COVID and then dying from a superbug?”

Strathdee witnessed first-hand the severity of a superbug infection when her husband, Tom Patterson, was infected by Acinetobacter baumannii, a nightmare pathogen that has evolved to outsmart medical treatments.

“This organism is something of a bacterial kleptomaniac. It’s really good at stealing antibiotic resistance genes from other bacteria,” she said.

“And when we were throwing antibiotics in somebody to try to cure them, it kills everything but this little guy. And then it just multiplies and moves in for the kill.”

It started when they were on vacation in Egypt in 2015. Patterson became violently ill with what they thought was food poisoning.

“I was vomiting for hours. It was just uncontrollable,” Patterson, who is a professor in the department of psychiatry at UCSD. “I was just getting sicker and sicker.”

“I thought we have antibiotics for this, right? Whatever it is, modern medicine can handle it. But no…it turned out that it was the worst bacteria on the planet,” Strathdee told Global News.

By the time Patterson was medevacked to a hospital in San Diego, near their home, his superbug had become resistant to all antibiotics.

“The doctors and nurses, people would come in and they would say it’s futile. He’s going to die,” he said.

Patterson was in a coma, on life-support and he had lost about 100 pounds. Doctors turned to Strathdee to ask if she wanted to keep her husband alive.

Strathdee recalls it as “the most terrifying moment of my life.”

She didn’t know what to do. Strathdee said she remembered reading a scientific paper that mentioned the last sense to go in a dying person is their hearing. So, she went to Patterson for help with the decision.

“So, I asked him, ‘Honey, you know, the doctors are doing everything that they can, but they don’t have anything left to fight this thing. So, if you want to live, please squeeze my hand and I will leave no stone unturned,'” she said.

Strathdee waited and Patterson squeezed her hand. She was ecstatic and immediately set to work searching for a solution.

With no treatments options left, Strathdee turned to bacteriophage as a last resort — a nearly century-old therapy.

“Bacteriophage, or phage for short, are parasites of bacteria. They are viruses. There are 100 times smaller than bacteria, and they have evolved to be the perfect predator of bacteria,” she told Global News.

Phages are everywhere. They can be found in a variety of places including in soil, water and animal waste.

They need a host survive. But phages are picky. Each one has its own preference and will only hunt a particular type of bacteria, or those in the same family, to kill.

“They were actually discovered by a French Canadian, Félix d’Hérelle, a microbiologist. … He was the first person to use phage therapy on people,” Strathdee told Global News.

“But when penicillin came on the scene around the time of World War Two, it was a miracle drug. And so the West forgot all about phage therapy.”

Since there are more phages on earth than bacteria, finding the right match for Patterson’s superbug wasn’t going to be easy.

She reached out to phage researchers for help. In three weeks, Strathdee said they had two purified phage cocktails to give Patterson.

“Even though one of the doctors described this as like a Hail Mary pass at the end of the football game, …Tom woke up a couple of days later,” Strathdee said.

Patterson remembers just waking up slowly and “there was my daughter.”

It’s been more than five years since phage therapy saved his life. And it’s taken almost as long for Patterson to recover.

During that time, the couple has turned their anguish into action, helping those facing a similar health state by collecting samples of sludgy water, sewage and animal waste — anywhere they think they can find an abundance of phages.

Strathdee also went on to launch and now co-direct the Center for Innovative Phage Applications and Therapeutics at UC San Diego. It’s the first dedicated phage therapy centre in North America.

“This is being upheld as the potential answer to the superbug crisis,” she said. “And in fact, we’ve gone on to use this treatment to save other lives and limbs.”

Comments

Comments closed.

Due to the sensitive and/or legal subject matter of some of the content on globalnews.ca, we reserve the ability to disable comments from time to time.

Please see our Commenting Policy for more.