Editor’s note: This article has been updated to remove incorrect information provided by the University of Alberta.

Researchers at the University of Alberta say they have reached a milestone in the efforts to get people with diabetes off injected insulin for good.

A recent first-in-humans clinical trial is reporting early signs that pancreatic cells grown from stem cells can be safely implanted, and in some cases, begin to produce insulin.

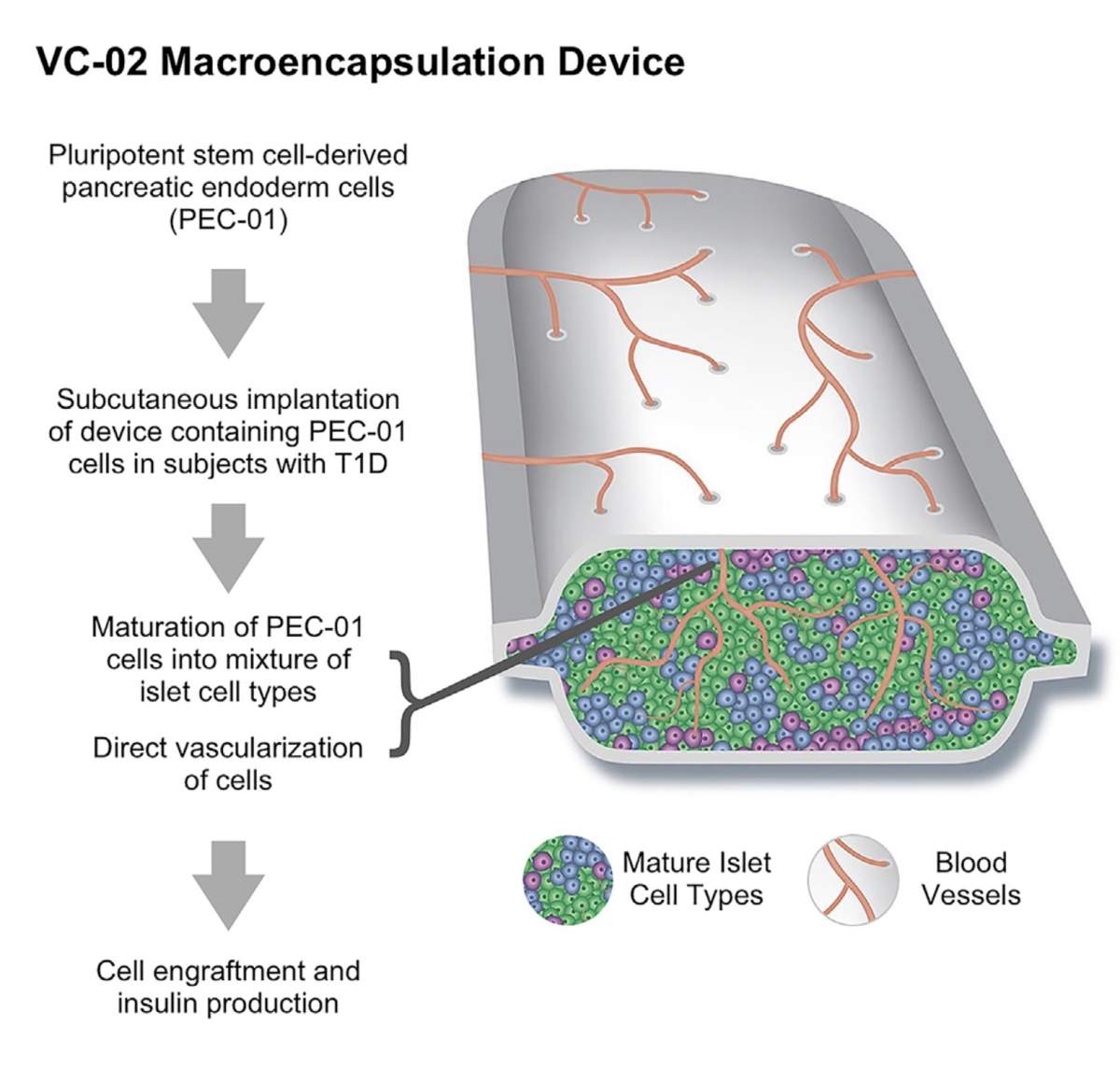

The trial saw 17 adults with Type 1 diabetes at six centres in Canada, the United States and Europe receive implants of pluripotent stem cell-derived pancreatic endoderm cells.

Each patient received implants of several small permeable devices filled with millions of cells each. The cells were derived from stem cells then chemically transformed into stem cells programmed to become islet cells.

Of the 17 patients who received implants, U of A researchers said 35 per cent showed signs in their blood of insulin production after meals within six months of the implant. On top of that, 63 per cent had evidence of insulin production inside the implant devices when they were removed after a year.

Get weekly health news

“This is a very positive finding,” said James Shapiro, professor of surgery, medicine and surgical oncology in the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry.

“It’s not the endgame, but it’s a big milestone along the road to success, demonstrating that stem cell-derived islet therapies are safe and can begin to show some signal of efficacy in patients in the clinic.”

Shapiro also led the team that developed the Edmonton Protocol in the 1990s, which developed a way to transplant donated islet cells, reducing their need for insulin. However, the U of A says patients continue to need anti-rejection drugs — which can have side effects such as an increased risk of cancer and kidney damage. The number of donated islet cells is also limited.

Shapiro said the main goal of this phase of the trial was to ensure safety, but added at least one patient who had 10 devices implanted was able to significantly reduce her insulin dose, which indicates the potential effectiveness of the treatment.

“We’re seeing some improvement in the patients’ blood sugar, but these cells are being transplanted right now in only very small quantities, so we’re not expecting big changes in insulin requirement,” Shapiro said.

“But we can see in about 65 per cent of devices that we take out from under the skin that there are human insulin-producing cells surviving, and in about a third of patients they have measurable insulin levels in the bloodstream. So it’s a really good first start with this treatment, I’m very excited about it.”

The ultimate goal of the new research is to develop an unlimited supply of islet cells that can be safely transplanted without the need for anti-rejection drugs.

“We’ve seen a lot of advances in the last 100 years since the Canadian discovery of insulin,” Shapiro said. “The race isn’t over yet, but we’re on our last laps and I really do believe that we can cross that ribbon.

“Cell-based therapies have the promise to deliver something far better than insulin therapy.

“Again, we’re not expecting to be curing diabetes in the first wave of this, we’re trying to do safety testing for first patients. And we see that really is helping mankind in the future of diabetes rather than any particular one patient at this point, but it will change as we move forward.”

The next step will try to determine how many stem cell-derived pancreatic cells are needed for transplant to optimize insulin production in patients with both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.