This past year has been a real wake-up call in B.C. in terms of climate change.

The province experienced an historic and deadly heat dome in June, extensive drought and another devastating wildfire season, and unprecedented bomb cyclones in the Pacific Northwest.

The biggest international conference on climate change, COP26, is going right now in Glasgow with more than 30,000 people from around the world and is showing to be unlike any conference before.

Several interviews with delegates from the University of British Columbia revealed a widespread sense of urgency and a resurgence of hope after the world came together to battle COVID-19.

“We don’t have a lot of time and this may very well be the last conference that can still have an impact before things become too difficult and too challenging,” Walter Mérida, one of UBC’s eight conference delegates, said.

Added fellow delegate Temitope Onifade: “The COVID-19 pandemic has shown us that the world can really address urgent issues if they want to.”

The conference aims to tackle two main issues that the Paris Agreement, set at COP21 in 2015, failed to address: Securing substantial global-emission reduction targets and finalizing the Paris Rulebook, a list of specifications or guidelines on how to implement the agreement.

“That (was) a political breakthrough on its own right,” Mérida said about the Paris accord, the first legally binding international treaty on climate change. “But it was insufficient to really make things happen.”

Secure substantial global emission reduction targets and keep 1.5 degrees within reach

COP26 is the first major milestone after the Paris Agreement, when countries are required to come back to the table with increased ambitions to their cut greenhouses gas emissions.

The goal is to aim for net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 in a bid to keep global warming well below 2 C, and preferably to 1.5 C — a benchmark set by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

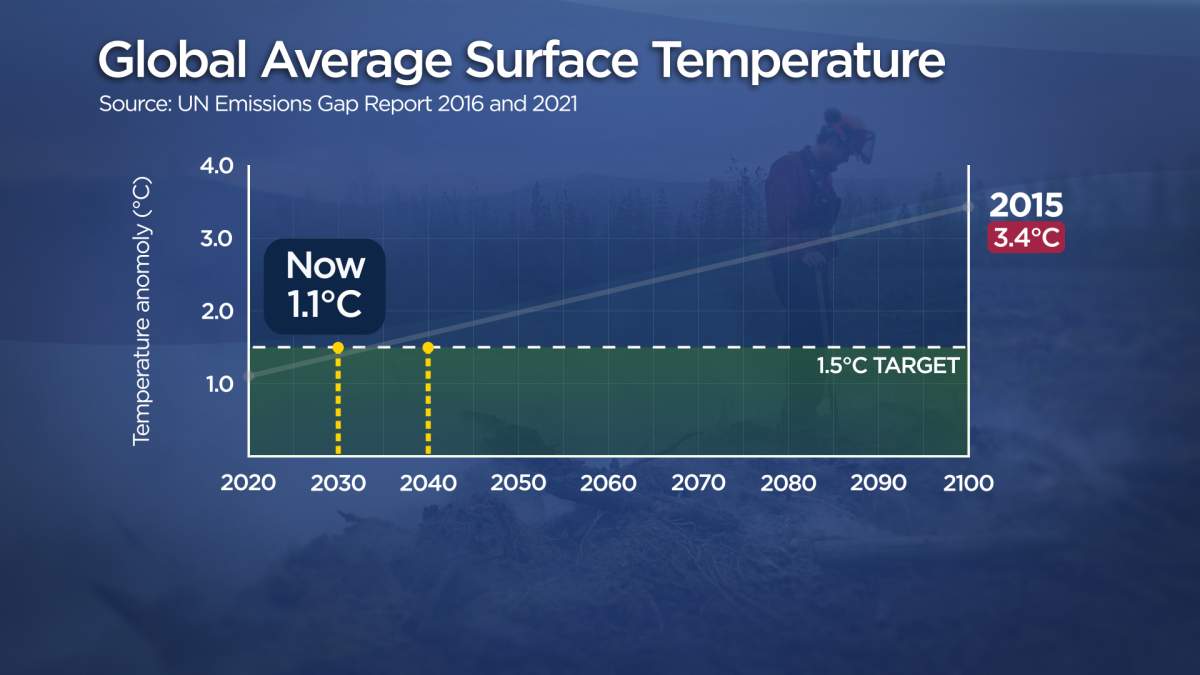

But the commitments submitted by each country in 2015 put the world’s trajectory of global warming to 3.4 C.

“Time is running out,” UBC delegate Kathryn Harrison said. “The carbon budget to limit global warming to 1.5 C — 80 per cent of it has already been used.

“We are on track to hit 1.5 C somewhere between 2030 and 2040, according to the international scientific community. That means increasing ambition this year at this COP, in setting targets ideally for 2030, is especially important because if we don’t do that, we’ll have lost that opportunity.”

Get breaking National news

Countries’ commitments going into COP26, according to the UN’s Emissions Gap Report 2021 aim to put the global warming trajectory to 2.2 C. The scientific community hopes these commitments will grow even further through discussions at the conference.

Finalizing the Paris Rulebook

One of the most complex and controversial pieces of the Paris Rulebook is Article 6, which is yet to be finalized. It’s meant to outline the rules on carbon markets to create a fair and transparent mechanism for emissions trading.

“They have been working on the rulebook for a number of years now,” Onifade said. “But we are hoping that they are going to make final decisions so that we can then just focus on implementation and not just drafting rules and drafting documents.”

Building a carbon market means to put a price on carbon and allowing a market-based strategy or ‘cap and trade’ system to lower global emissions.

Many organizations, like the Environmental Defense Fund, support the approach as it can motivate countries to lower emissions as well as give them flexibility to manage their targets.

This is done through emissions trading or carbon offsets — allowing countries that cannot meet their emissions targets to purchase credits from another country that has overshot its targets.

Other leaders, like Harrison, would prefer this article didn’t exist.

At best, emissions trading may make it less expensive for countries to reach their targets, she said. For example, a country with a high emissions target may find it less expensive to purchase emissions credits from another country who has overshot their low emissions target.

“Then the world would have the same amount of emissions reduction at a lower cost,” she said. “At its worse, it could undermine the whole Paris Agreement if the credits that countries or individual firms can purchase in other countries are bogus.

“If they are emissions reductions that would have happened anyway, then what we’re doing is giving that firm or that country credit as if they made a reduction when nothing new actually happened.”

How COP26 could affect B.C.

Onifade said the positive implications include reducing harmful events such as wildfires, floods and heat waves.

“Also, B.C. would be able to key into the idea of carbon markets. So that would mean that there would be newer jobs, cleaner jobs, newer technologies.”

Said Mérida: “I really believe that B.C. can become a global resource for a low-carbon economy.”

B.C. is already leading the way in two ways, he said.

“In terms of technology breakthroughs, we have one of a few globally relevant carbon capture companies, we have one of two leading fusion energy companies and we have hydrogen technology companies. So we are slowly building our very rich ecosystem for the type of innovation that will be required to accelerate these solutions.”

And, in addition to B.C. being the first jurisdiction in North America to introduce a carbon tax, he said the province also has a low-carbon fuels credits program that encourages investment on deployment of low carbon fuel solutions.

“So it’s not just the technology, but also the policies that can accelerate the transition to a low-carbon economy,” he said. “I think B.C. has a huge opportunity to become a globally relevant centre of innovation for the new the new energy system.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.