When many people think of Fort McMurray, Alta., they picture an urban centre in close proximity to the oilsands and a place to house the workers that extract its valuable fossil fuels.

While that is an accurate description of the place many call “Fort Mac,” the relatively remote community is perhaps less known for how picturesque it is in many ways; situated in the boreal forest, with many streets built on hills and surrounded by waterways.

“I still say that there’s no better place to live in Canada than Fort McMurray,” says Don Scott, the mayor of Wood Buffalo — the municipality in which Fort McMurray is located.

“We’re in the middle of a forest… There’s a lot of natural beauty that surrounds us. I can’t imagine living anywhere else.

“I know a lot of Albertans, once they visit this region, they’re very surprised at how gorgeous it is… There is no better place to be.”

Five years after a catastrophic wildfire tore through the community, the fact that it is in a boreal forest is much more front of mind for politicians, emergency officials and the people who live there.

READ MORE: Alberta study suggests schools, ring roads and parking lots can help prevent spread of wildfires

“Wildfire still remains the No. 1 risk in our region,” says Erin Fleming, who supervises a fire prevention and mitigation program called FireSmart for the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo.

Wood Buffalo implemented the national FireSmart program in the wake of the 2016 disaster to reduce the risk of wildfire damage.

The fire half a decade ago destroyed 10 per cent of Fort McMurray’s buildings and resulted in $3.8 billion worth of insured damages.

A report commissioned by the municipality in the wake of the fire came up with 14 recommendations aimed at preventing a repeat scenario. Regional fire chief Jody Butz says the municipality has already implemented 13 of them.

“We have addressed a lot of those risks and we have reduced the risk,” Butz says. “I feel a lot more confident than we did before.

“It’s really about the resiliency of our region, and I’m proud to be a part of it.

“The idea is to be able to absorb, adapt and recover… in a timely fashion.”

READ MORE: Final Fort McMurray wildfire report indicates misunderstanding over seriousness of threat

Fleming says she’s proud to be involved with Wood Buffalo’s FireSmart program and that she actually believes the job has helped her to heal from the trauma of the 2016 wildfire.

She says learning more about how to mitigate the risk of fire helped inform her when she rebuilt her own home.

“It’s been very therapeutic and I feel like being part of rehabilitating Fort McMurray after the wildfire — when I was in the recovery task force and then moving from that into FireSmart — and having the opportunity to educate residents, it’s been so therapeutic for me personally to help me get over the 2016 wildfire,” she says.

“The house that I rebuilt, I made decisions that I probably never would have known to make before, such as my siding choice, such as my decking material, the importance of skirting in your deck… the importance of not having mulch within 10 metres of your house or having your shed within 10 metres of your house.”

READ MORE: Fort McMurray residents preach resilience 5 years after wildfire swept through community

Fleming says more knowledge about fire has made her understand that’s it’s not always just bad luck when one home is more damaged than another.

“I never really thought about the science behind it,” she says.

Fleming says the components of the FireSmart program are education, vegetation management, cross training, emergency planning, planning inter-agency co-operation, legislation and planning and development.

“In 2017, the wildfire mitigation strategy was released for our region. And in that mitigation strategy, a lot of forested areas were identified as high-risk areas for future wildfires,” she says.

Much of her job revolves around removing hazards she calls “extra fuel” sitting on the forest floor, removing dead or diseased trees and looking at better spacing coniferous trees, which she calls “a highly flammable tree species.”

Fleming says her team visits with homeowners to look at ways they can help to mitigate the risk of wildfire on their own properties but says some people fear all measures will cost them money they can’t afford.

Get breaking National news

“But there are so many steps that people can do, such as moving woodpiles away from their property, moving flammable materials outside of the non-combustible zone which is 0 to 1.5 metres, making sure that their sheds are outside of that non-combustible zone, cleaning their gutters on their roof,” she says.

“If they’re going to be replacing their decking material, putting down composite decking material which is less flammable than wood.

“There’s a lot of things people can do that don’t cost a lot of money and it would really have an impact on wildfire damages to their property.”

READ MORE: Fort McMurray embraces plan to bolster wildfire prevention in region

Wood Buffalo officials say since the 2016 wildfire, about 341 hectares of municipal land have been treated with FireSmart prescriptions.

All of Wood Buffalo’s work on wildfire mitigation has not gone unnoticed. Three years ago, the municipality was presented with the FireSmart Canada Community Protection Achievement Award, which is presented to communities who have made significant steps towards implementing FireSmart solutions.

Tara McGee is a professor at the University of Alberta, whose work focuses on responses to environmental hazards. She went north to Fort McMurray after the mass evacuation in 2016 to get a better sense of how that process unfolded.

“It was interesting to go up there shortly after such a big event for that community but also for Edmonton as well — many evacuees ended up here,” she says.

“One of the things that really struck me was the importance of emergency planning — really having a plan in place that really thought about the worst-case scenario…and so making plans accordingly.

“I don’t think they were in place before the fire but certainly, subsequently, I’m hoping that their planning does a better job of incorporating that.”

McGee said such a disaster should also underscore the important of land-use planning.

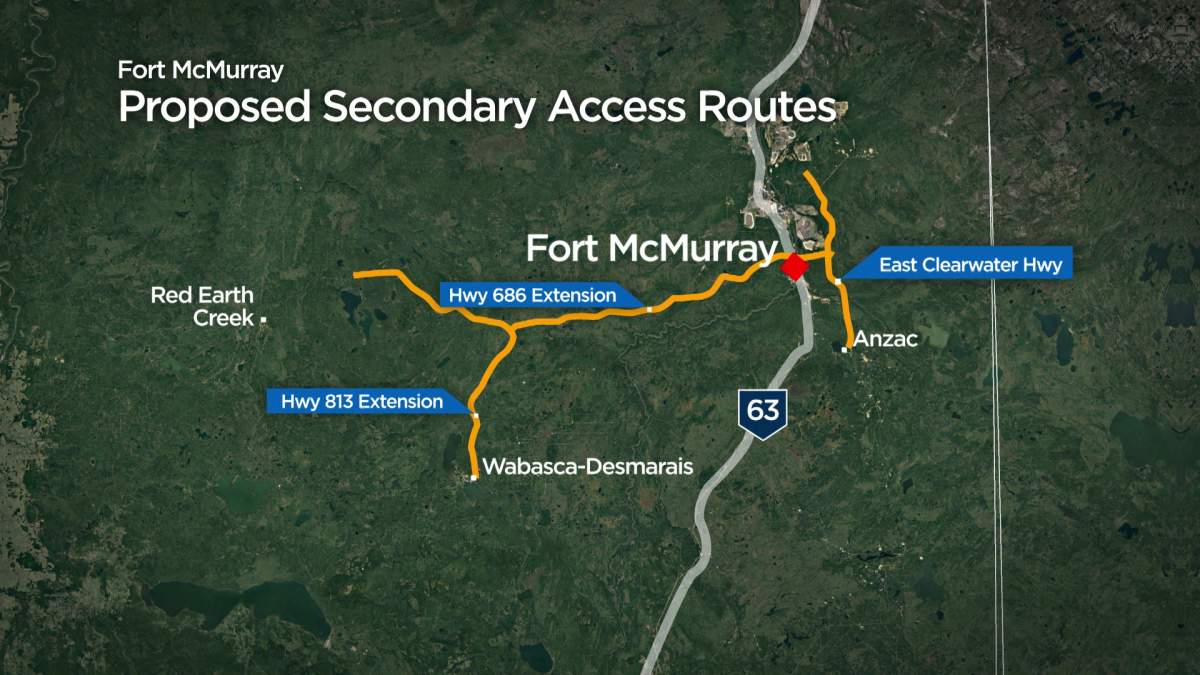

“In that city, transportation, people getting out of their neighbourhoods,” she says. “The one way in, one way out onto the highway and then of course just having the one highway out.”

Before losing the 2019 election, one of the Alberta NDP’s campaign promises was to build a second road going in and out of Fort McMurray.

Wood Buffalo has endorsed what’s been called the East Clearwater Highway route, which would run east of the city and connect to Highway 63.

A spokesperson for Alberta Transportation said the province is working with Wood Buffalo on a study to determine the benefits and disadvantages of that route and expects to have the assessment completed before the summer.

- Tumbler Ridge B.C. mass shooting: What we know about the victims

- There are changes coming to Tim Hortons menus and stores soon

- ‘We now have to figure out how to live life without her’: Mother of Tumbler Ridge shooting victim speaks

- Family of Portapique victims offers advice and support to community in Tumbler Ridge

An alternate route is also being considered. Alberta Transportation says that route would extend Highway 686 west of Fort McMurray to Peerless Lake and Wabasca-Desmarais, which is roughly in the middle of the province.

However, the province says that route is not part of the East Clearwater Highway study and design work has not been completed.

Butz says more than anything, the legacy of actions taken by Wood Buffalo on wildfire mitigation since 2016 will be that all decisions made in the region will be made through a lense of asking what the potential impact could be on wildfire risk.

“It’s an inter-departmental approach to disaster risk reduction,” he says. “The boreal forest will continue to regenerate… We live in the boreal forest and the threat of wildfire is always real.

“(I’m) very happy to say we’ve reduced a lot of that (potential) impact.”

Fleming says she has already seen the fruits of her labour.

“In 2019, there was a forest fire — a really quick spot fire — on the other side of the Birchwood Trails in Timberlea,” she says. “It was noticed very quickly and the fire response team was able to get in there very quickly .

“It’s presumed that due to the FireSmart treatment that we had done in the area, the fire did not spread quickly. It was noticed quickly and the area was nice and open so firefighters could get in there to extinguish the flames very quickly.”

Fleming adds that when she speaks to homeowners who are skeptical about how beneficial implementing FireSmart precautions on their properties really is, she has a response.

“Some say, ‘You don’t understand… You haven’t been through this.’ Well, yeah, I have… I have a vested interest in this community… I love it here,” she says, explaining she too lost her home in the wildfire.

“I was born and raised in Fort McMurray. I was always surrounded by the boreal forest. I was one of those people that grew up with wildfire but I never really expected that it would impact the city in the way that it did in 2016.”

BELOW: Erin Fleming’s home before and after it was destroyed in the 2016 Fort McMurray wildfire

Flood mitigation

While the terrifying scenes of flames consuming parts of Fort McMurray are memories burned into the minds of many Canadians, significant flooding is in many ways just as formidable a threat to the community as wildfires — and the floods occur more regularly.

“Floods have happened in this region for 185 years, so we have spent a considerable amount of money on permanent flood mitigation,” Scott says.

“We never know what we’re going to face.”

According to Scott, the devastating flood in downtown Fort McMurray last year has prompted the municipality to be better prepared now than it ever was.

In April 2020, 13,000 people were forced to flee Fort McMurray when ice jams led to major flooding by causing the Athabasca and Clearwater rivers to overflow their banks.

The flood caused damage to at least 1,200 structures and resulted in hundreds of millions of dollars in insurable damage to businesses, homes and vehicles.

READ MORE: Fort McMurray cleans up from flood on anniversary of 2016 wildfire evacuation

Scott says Fort McMurray was facing a similar level of risk this spring as before the flood last spring but the community is much better prepared to mitigate the impact of any potential flooding.

He says $10 million has been dedicated to flood mitigation work for this year alone and over $250 million is being spent on permanent flood mitigation, work which should be done by next year.

In the fall, the municipality said crews had installed temporary clay berms downtown and in other communities that were hit.

Scott says after a report in December raised concerns about flaws in the berms, the municipality’s administration made great efforts to address the issues.

“These issues should have been addressed decades ago,” he says. “This is the council that’s actually taking action.

“We have done our best to prepare for it. I am confident with what I’ve seen.”

Karl Behrisch is a longtime resident of Fort McMurray who owns three properties in the community. All three were seriously damaged in last year’s flood.

“I’m aware of the risk,” he says. “We’ve become more aware.

“When you drive around, you see what they’ve done. Downtown has always historically been a flood zone.

“I have every confidence that Fort McMurray city government is doing everything that they can because they have to protect the investment which the lower townsite represents.”

READ MORE: Fort McMurray residents still cleaning, considering options after spring flooding

Despite all of the municipality’s work on flood mitigation this year, Behrisch says he has filled sandbags to be ready, just in case.

“I’m not being naïve,” he says. “We’re doing what we need to do, but are also aware that the town has measures in place.”

Behrisch says people have known about the flood risk in Fort McMurray “forever” and that the idea of one-in-a-hundred-year floods isn’t a very useful concept in some ways.

“(It) might not be 100 years,” he says.

“Dice have no memory. It could happen next year, right?”

McGee says it’s important for people to truly grasp what the once-in-a-century flood concept actually means.

“If you’re living on a 100-year flood plain… it essentially means every year there’s a one per cent chance of a flood,” she says. “Whether people know about that is an interesting question.

“After a big event, we want to get on with our lives, but it is important for people to realize that if you’re in a flood plain, there is a chance every year that there will be a flood event.”

McGee says the lower townsite in Fort McMurray is truly a flood plain.

“Building in flood plains — there are risks associated with that,” she says.

Butz says the community acknowledges the natural risks it faces each year and continues its work to mitigate those risks as best as it can while noting Mother Nature’s power is always formidable.

“Once we get through the river breakup, then we can turn our attention to wildfire,” he says. “Hopefully the two don’t overlap, but only Mother Nature will dictate that.”

–With files from Global News’ Breanna Karstens-Smith and The Canadian Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.