Black Lives Matter in London, Ont., is calling on the city to defund its police force.

As a result of worldwide protests, along with a renewed, heightened awareness and public discourse over anti-Black racism and police brutality, there is a growing movement to defund police departments across North America and redirect those funds to social services, including in London.

Alexandra Kane, a spokesperson for Black Lives Matter London, says the group is pushing for “real, actionable changes within the system.”

“We want to see the police be defunded and reallocating those funds and pouring them back into the community. We need to see funds supporting social services. There are people who are, you know, disenfranchised — the homeless, we want to see people who aren’t ticketed for being homeless,” she explained.

“The system really does focus a lot on Black people and Indigenous people and criminalizing them. And we want to make sure that this stops.”

Kane also referred to the recent deaths of Caleb Tubila Njoko, a Black man in London, and Chantel Moore, an Indigenous woman in New Brunswick, both of whom died after police were called for a wellness check.

Ontario’s police watchdog, the Special Investigations Unit, is investigating Njoko’s death, while New Brunswick’s public safety minister has said an investigation into Moore’s death is underway through Quebec’s independent police investigation agency, along with a New Brunswick coroner’s investigation.

“There’s a lot of conversations around recent deaths surrounding Caleb here in London or Chantel (who recently moved from) B.C., and there’s a lot of ‘Well, if a social worker had shown up to answer this call, they could still be alive.’ We take that to heart, we take that to mean something that, ‘Hey, listen, we need to pay attention. We need to wake up,'” Kane said.

“You know, Black people, Indigenous people have a fear of the police, you know, and when they show up, if you’re in a different mental state and they show up, you’re scared. There’s a fight-or-flight response. And there are people in this world trained to handle that, and it’s not the police.”

Chair of the London Police Services Board, Dr. Javeed Sukhera, says the idea of defunding police is “a concept that I want and the board has been wanting to lean into.”

“We are trying to understand what it means in our context in London. The words ‘defund the police,’ they mean different things to different people,” Sukhera said.

“I think there’s one extreme end of that continuum that speaks to abolishing policing entirely — that’s definitely not where our heads are at. But at the same time, I appreciate that incremental baby-step approaches to reform really haven’t addressed a disproportionate impact of anti-Black racism on communities within London, and that means we need to reimagine how we do what we do.”

Sukhera says a blanket call for cuts “isn’t always helpful unless the money that’s being cut is going to be invested into something that is helpful and unless the impact of that cut is really appraised in terms of what that’s going to mean for our community.”

Get daily National news

He says the board wants solutions that “aren’t about optics or lip service” and that the board is in conversation in partnership with the senior police administration.

“I believe each and every one of us has racial bias that is contributed to based on systemic and structural bias in our society. I myself have racial bias that impacts how I think and how I approach people, and that’s an endemic problem in all sectors of our society, including health care, where I work, as well as policing,” he added.

“At the same time, I have encountered incredible examples of the highest level of professionalism amongst the officers and the police service members that I’ve encountered.

“That doesn’t mean there aren’t problems, that doesn’t mean there aren’t things we need to address, that doesn’t mean systemic racism isn’t a huge issue because it is. But that’s a problem for all of us to work on.”

London’s top cop, police Chief Stephen Williams, believes these issues revolve around “trust and confidence in policing” and argued that “it’s not as simple as just defunding police because we provide a valuable service to the community which people expect.”

“I think what people have to realize is that although policing is similar throughout North America, in some ways, it’s also very different. Policing in Ontario and in London is different than outside of the province. We have a funding model that is based upon what we’re legislated to do, what we’re required to do pursuant to the policing regulations in the Police Services Act,” he explained.

“When we formulate our business plan and we do the budget process with our board, we do a lot of public consultations with different groups, business groups, private citizens, community groups, things like that. And all that informs our process.”

Williams added that much of what police do is not what would be considered “traditional police work.”

“There’s a number of social issues, particularly in this city but not just in London, revolving around homelessness, addiction, mental health and all that,” Williams said. “We are still the only 24-7 service that responds to these complaints. We are the 911 for these problems.

“We never asked for this portfolio but we are doing the job of social workers. Our officers do it because they’re professionals and they’re committed, and when they get the call, they answer the call.”

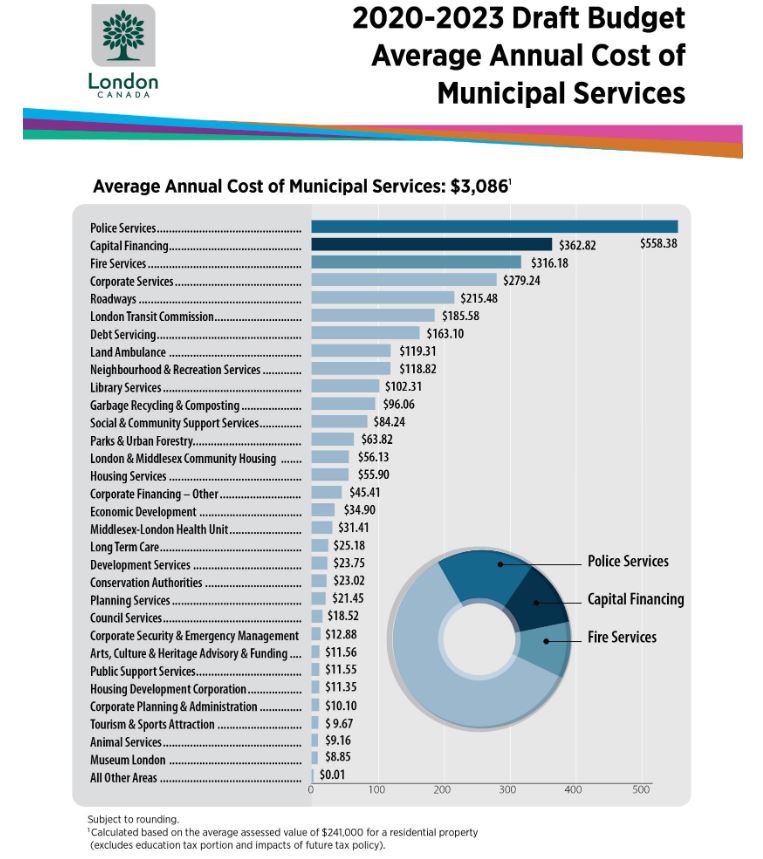

Policing is, by far, the largest item in the City of London’s budget.

The amount of funding allocated to police has gone from $79,932,000 in the 2010 council-approved budget to $107,935,000 in the 2019 council-approved budget update — a roughly 35 per cent increase.

In that same time frame, the entirety of the city’s operating budget grew from a budget of $829,400,000 in the council-approved budget for 2010 to $949,352,000 in the 2019 council-approved budget update, which marks a roughly 14 per cent increase.

When it comes to limiting the growth of the police budget, councillors are in a difficult position.

In 2016, councillors tried to “control budget growth,” and the police force appealed to the Ontario Civilian Police Commission. A settlement was reached in late 2016.

Additionally, under the Ontario Police Services Act, councillors do not have the authority to defund specific areas of the police budget.

On Monday, two councillors in Toronto announced a desire to defund that city’s police force by 10 per cent and use the money for community resources. Coun. Josh Matlow said the motion, if passed, would include several measures.

First, Toronto council would ask the province to amend the Police Services Act so that the city has the authority to approve or reject specific items in a budget. Second, he wants the police to draft a 2021 budget that is 10 per cent lower than 2020’s. He also wants a line-by-line breakdown of the proposed budget.

Meanwhile, investments in the social and health services section of London’s city budget have been difficult to gauge, in part due to funding changes between the province and municipalities over the last decade.

A city spokesperson stressed that provincial funding changes explain the decrease in city funding for the social services portion — which covers items like homelessness prevention, immigration services and Ontario Works — of the social and health services section of the budget.

That portion dropped dramatically from $33,205,000 in 2010 to $15,868,000 in 2019, but in an email to Global News, a spokesperson noted that “in 2012 the provincial share of the program supports to recipients was 83 per cent, whereas in 2018 that funding ratio shifted to 100 per cent provincial.”

“Thus, while the city tax levy-supported contributions have decreased, the contributions from other levels of government have increased. Case in point, the Ontario Works expenditures have increased an average of three per cent per year from approximately $123 million in 2010 to $155 million in 2019,” the spokesperson told Global News.

Still, while the city is no longer responsible for service costs associated with these programs, the programs themselves have seen little investment from the province, and the first budget from the Doug Ford government included $1-billion in cuts to the Ministry of Children, Community and Social services as well as controversial municipal funding cuts for public health and child care.

According to the Income Security Advocacy Centre, Ontario Works benefits went from $585 per month for a single person before November 2010 to $733 as of June 2020 — an increase of approximately 25 per cent. Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP) rates went from $1,042 for a single person per month to $1,169 per month over the same time frame — an increase of just 12 per cent.

Housing, another segment of the social and health services section of the budget, has seen recent growth amid what’s been dubbed an “affordable housing crisis.”

From 2010 to 2019, the housing portion of the social and health services section of the city’s budget grew from $18,826,000 in the council-approved budget of 2010 to $24,258,000 in the council-approved budget of 2019, an increase of roughly 28 per cent.

That section of the budget also saw the introduction of the Housing Development Corporation in 2016 as well as some controversy over London and Middlesex Community Housing (LMCH) in 2019 following an independent review of both bodies, which found that the LMCH was hindered by a lack of governance oversight mixed with a higher-than-normal vacancy rate.

— With files from Global News’ Andrew Graham and the Canadian Press’ Allison Jones and Liam Casey

Comments