The Ecofiscal Commission never comes right out and says so in its most recent report, just released Wednesday, but it is pretty easy to read between the lines to get the message that it is encouraging all major political parties, federal or provincial, to be more honest with voters about their climate change policies.

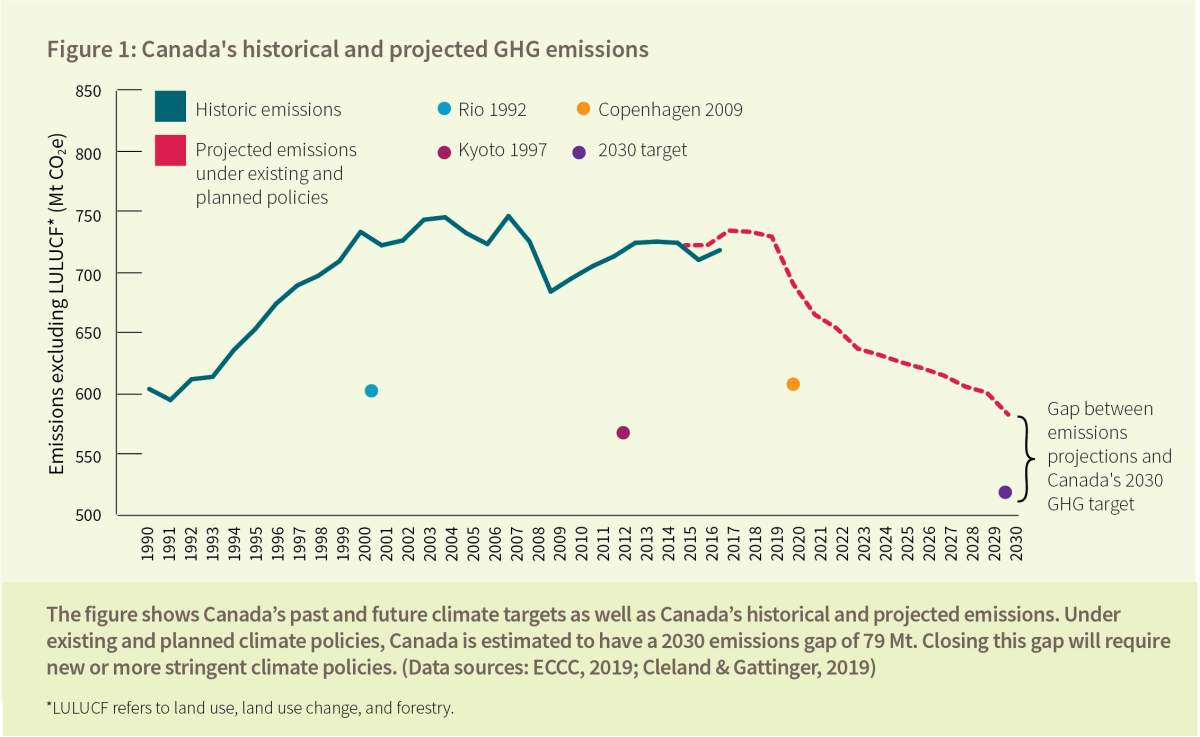

That honesty would have to start with an admission by those parties in power in Ottawa and in provincial capitals: Canada will not meet its international commitments to lower greenhouse gas emissions.

Secondly, it would require some honesty from politicians in power and seeking power to tell voters about the economic costs and benefits of whatever it is they are proposing to get Canada to hit its climate targets, which it committed to at the Paris climate change conference just after the 2015 election.

The country’s two leading federal parties — Justin Trudeau’s Liberals and Andrew Scheer’s Conservatives — are in complete agreement, it should be noted, when it comes to the targets agreed to in Paris.

And while a Liberal prime minister — Trudeau — actually signed the Paris Accord, the details of that agreement were worked out, by and large, by Canadian officials working for the previous Conservative government of Stephen Harper.

Indeed, to quote from the Conservative climate change plan tabled just this last June: “Canada’s pledge for the Paris Agreement is to cut emissions by 30% below 2005 levels by 2030. These targets were developed by the previous Conservative government. The Paris targets are Conservative targets.” That’s on the record from the Scheer Conservatives!

So all agree that action is required and all agree on the objective of that action. Not all agree, of course, on what form that action is to take.

“Governments – plural — federal and provincial governments– that want to achieve deeper emissions reductions have options about what they can choose,” said Chris Ragan, the McGill University economist who is the chairman of the commission.

Broadly speaking, conservative-minded parties, like the federal Conservatives or Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservative Party in Ontario, do not believe climate action should involved pricing carbon either via a carbon tax or a cap-and-trade system.

Instead, those parties favour a mix of regulations and government subsidies of new technologies to achieve emissions reductions.

Get breaking National news

Non-conservative parties believe carbon pricing is the best way to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

And since the current federal plan involves carbon pricing, that’s where the latest Ecofiscal Commission report starts, by evaluating the current federal plan and then taking that plan and comparing it to other plans that do not involve carbon-pricing.

To do this, the commission developed three different ‘packages’ of policies to compare, and in doing so, it stuck to these two crucial variables: Each package must get Canada to the 2030 target of cutting emissions by 30 per cent compared to 2005 and each package must be revenue-neutral — that is, the government that implements any of the packages must find the means to disburse any revenues it collects, or find a way to pay for any subsidies it offers.

Ecofiscal’s conclusion at the end of this exercise was hardly revelatory, in that many other researchers have come to the same conclusion: A carbon tax-and-rebate program is the least costly way to cut greenhouse gas emissions. It would simultaneously allow Canada to increase its GDP-per-capita — we’d get wealthier — while cutting emissions as we promised the world we would — we’d be greener.

“It is the most visible, but it is also the best for the economy,” Ragan said. “It is the least cost policy and it’s the least cost by a considerable chunk.”

It might be worth noting at this point that Ecofiscal has no partisan axe to grind.

The Ecofiscal Commission created itself six years ago, made up of economists who hail from all parts of the country. If there is a partisan bent among its members, it is not a common partisan bent. These economists are supported by an advisory board that includes a former NDP premier of British Columbia, a former Progressive Conservative finance minister from Alberta, a former Liberal premier of Quebec as well as former Liberal prime minister, Paul Martin, and former Reform Party leader, Preston Manning.

Its modest $1.3-million annual budget is largely covered by corporate contributions from the likes of oilsands giant Suncor and Bay Street titan TD Bank. The group’s work has never been funded by any government or any political party.

But despite its lack of a partisan bent, it was perfectly aware of the current state of climate change politics. With a recognition that there are political actors who are dead set against any kind of carbon pricing, the Ecofiscal Commission took a serious attempt to design two other ‘policy packages’ that achieved the Paris Accord targets everyone agrees to, but did so without a carbon-pricing mechanism.

For example, the commission modeled a suite of broad-based, economy-wide regulations combined with heavy government subsidies and concluded that package could get Canada to its targets. But for this package to be revenue-neutral, it would mean that taxes would have to be raised, somewhere in the ballpark of 1.5 per cent to 2.5 per cent, both personal and corporate.

Per-capita GDP would also grow in this scenario, but not by as much as a package that focuses solely on a carbon tax-and-rebate system.

The commission also looked at a third option, in which regulations and government subsidies are much more tightly focused on specific industrial sectors, such as energy or agriculture, which are the biggest emitters of greenhouse gas emissions. This was the least cost-effective package and was the package that came with most risk because of the difficulty in getting regulations that work just right.

To maintain revenue neutrality in this scenario, taxes would have to jump in the range of four to six per cent by 2030.

Now, a political party could pick up any one of those package or mix and match with some pricing mechanisms and some regulations. The key for voters who wish to assess one party’s package over another will be honesty and transparency when it comes to costs and benefits.

For example, the current Liberal carbon-tax-and-rebate program maxes out in 2022 at $50 a tonne. But in Ecofiscal’s models, carbon will require a price of $220 per tonne by 2030. For those still using gasoline-powered engines — which would likely be everything from tractors to heavy trucks to planes — that kind of carbon pricing implies an increase of about 40 cents a litre to the price of fuel.

When challenged on the campaign trail by reporters to say how much higher his government would be prepared to price carbon, Trudeau deferred the answer, saying that the next election, whenever that is, will be the time to put forward his party’s carbon pricing plans.

The Conservatives, not surprisingly, have loudly howled that Trudeau and the Liberals have a hidden agenda and should come clean.

But the Conservatives should come clean, too, if they are to be taken seriously on this file. First, they must present a robust and detailed regulatory approach — something they dismally failed to do in the last election — and then they must be honest about its costs compared to the alternative, carbon pricing.

How big would their deficits be if they subsidized consumers or industries to adopt new technologies? If no deficits, how big a tax hike would they impose on Canadians? And how would their plan improve GDP per capita versus others?

These are not academic questions any longer. They are the solutions our political class is putting forward to solve what the most pressing public policy challenge not just our time but arguably of all time.

“Climate change is real,” the Conservative leader, Andrew Scheer, declared on June 19. “It represents a serious threat not only to Canada but to our entire planet.”

Indeed. Perhaps it’s time politicians got serious with voters about the details of their plans.

— David Akin is the Chief Political Correspondent for Global News.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.