With a population of just 15,000, Brooks, Alta. is vastly different than the city Deepak Badola once called home.

“I’m from India,” the cheerful father of two says from his living room in the southern Alberta city. “I lived in Delhi a long time, everything in Delhi is very rushed.”

Badola moved to Brooks from Calgary a few years ago to open the community’s first Indian restaurant. So far, he says, business and life is good.

“Brooks is friendly, very friendly.”

One of the reasons the community is so welcoming to newcomers may be because their economy depends on it. A major meat processing plant operated by JBS Foods lies just outside the community.

As one of the community’s main employers, the plant pumps a lot of money into the community.

“You think about 2,600 workers, $3.2 billion of gross domestic product,” said Barry Morishita, mayor of Brooks. “They buy a million cattle a year from our cattle growers in the province, so it’s huge.”

The economic engine of the region, however, sputters to a halt without people and for years the meat processing plant has struggled to find enough workers within the local labour market.

But because work in meat processing doesn’t seem to appeal to enough Canadian-born workers, the meat industry has had to turn its attention elsewhere.

WATCH: (Aug. 26, 2019) Canadians respond to controversial anti-immigration billboard

“The labour pool in Canada isn’t sufficient,” said Marie-France MacKinnon, vice-president of public affairs and communications for the Canadian Meat Council.

“Our employment shortage up until a few months ago was almost 12 per cent, which is a record high. It’s higher than any other sector in Canada.”

Get breaking National news

The problem is that changes made to the federal government’s temporary foreign workers program in 2014 have made it difficult for meat processing plants to bring foreign workers to Canada.

It’s something the Canadian Meat Council has fought hard to change. Next January, a federal pilot program is set to launch that will help increase the number of newcomers who arrive in communities like Brooks.

Brooks, where one out of every three people in the community is a visible minority, is certainly used to newcomers.

Stand on the the city’s main street for a few moments, you’ll see faces from Africa, Mexico, the Phillippines, Colombia and beyond.

The city’s mayor says the diversity has enriched the community but there have been challenges, too, and he says there is a desperate need for more social support.

“Aside from the economic benefit, the goal should be to build communities and whether you go to our schools or other social services, we need to make sure supports are in place around creating these complete communities,” Morishita said.

Not everyone in Brooks is happy to see demographics change, though. Morishita says he still hears racist comments around town, while polls suggest a growing number of Canadians are becoming concerned that Canada is welcoming too many immigrants.

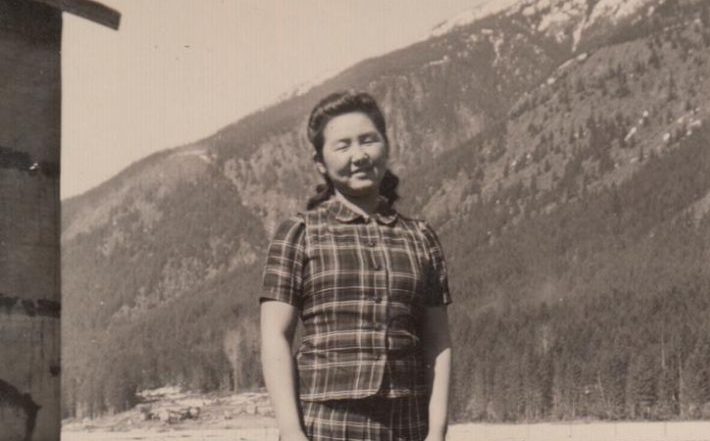

It’s something Maroshita says touches him in a deeply personal way, because it makes his think of his grandmother, who was identified as Japanese by the Canadian government during the Second World War.

After Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, more than 20,000 Japanese Canadians were rounded up and placed in internment camps in central B.C. and across the Prairies, or forced into labour.

“My grandmother was actually born here but she was interned in B.C.,” Morishita said.

Japanese Canadians lost almost all their property, as the government seized and sold it off during the war and used the proceeds to finance the internment, according to the Canadian Museum for Human Rights.

“My dad and my aunt were actually born in internment camps. She lost everything by being part of an identifiable group. The crisis is created by people who say, ‘you know, immigration is bad and that group of people is bad’ — yeah, it tugs at me.

“We need to educate people that immigrants are just people like us.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.