More than a century ago, access to an Indigenous midwife was common practice in First Nations communities.

However, accessing an Indigenous midwife in Canada today is now nearly impossible, according to Carol Couchie, an Indigenous midwife and co-chair of the National Aboriginal Council of Midwives (NACM).

The traditional practice ensured women could stay and give birth at home, without having to travel to larger centres, while also connecting with culture.

“Midwives could have been woven into the landscape of medicalized birth, and our culture could have been woven into it as well, to keep women safe. It didn’t have to be all or nothing,” Couchie said.

“It really depends on where they would live in the country. Unless you live in Toronto, then yes, it’s almost impossible.”

READ MORE: How hired postpartum help is becoming more commonplace for moms

Health Canada’s Non-Insured Health Benefits (NIHB) program provides First Nations and Inuit women with coverage for health services not available in their own communities.

In 2014-2015, 945 women received medical transportation coverage for air travel to access prenatal appointments. The average hotel stay for women was 10 days and cost approximately $879,000 in total.

Couchie said the push for more Indigenous midwives began about 35 years ago and has accelerated in the last decade, but is nowhere near sufficient.

Get weekly health news

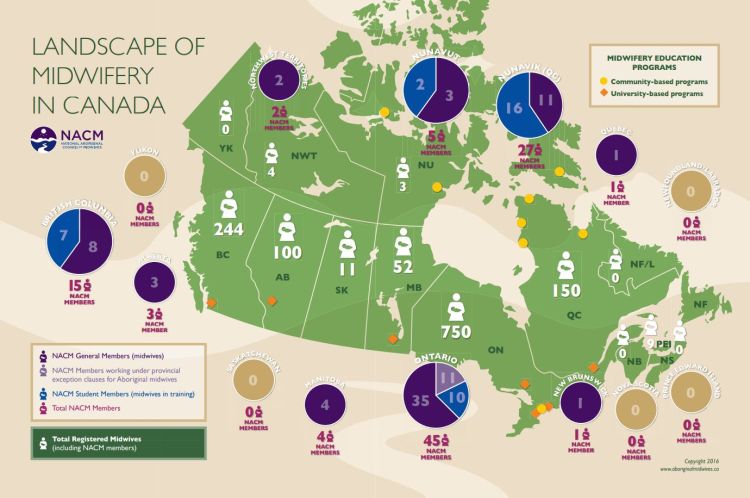

In Alberta, there were three Indigenous midwives in 2016, but in Saskatchewan, Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and the Yukon, there were none. In British Columbia, there were 15. In Quebec, there were 28 (mostly in the northern area of Nunavik) and in Ontario, there were 45.

“We’ve doubled since we started, but really we need the momentum to keep going,” she said.

What is an Indigenous midwife?

Indigenous midwives enable access to reproductive health care and help reduce the number of medical evacuations for births in remote areas, according to NACM. They are medically trained professionals who pass on cultural values about health to the next generation.

“We lost a lot and I really feel that our (health) stats as Indigenous women reflect that loss,” Couchie said.

“We have far better stats in places that are remote where we’ve had (Indigenous) midwifery than in the places that fly people out routinely.”

READ MORE: Why are parents reluctant to ask for help when they need it?

The goal is to eventually have Indigenous midwives available in all communities.

Couchie said education and funding for services are key for expanding the number of Indigenous midwives in Canada.

“We have to educate our own,” Couchie said.

“So, we’re going to need non-native midwives to help us get there, but we also need our own young people to start learning and be there at those births.”

Why connecting with culture is important

Freedom Bruce, 23, of Edmonton, grew up in government care and said she had limited exposure to her Indigenous culture. Bruce’s first child, her now-four-year-old daughter, was born in a traditional hospital setting with no connection to her culture.

When she became pregnant a second time, Bruce was introduced to an Indigenous doula.

“The first feeling that I felt was just this genuine compassion and love. I was so shocked. I was like, ‘This is no nice,'” Bruce said while attending a breastfeeding circle hosted by Indigenous Birth of Alberta.

“I didn’t even feel deserving of it.”

With the help of a midwife and surrounded by family, she delivered her son at home, while incorporating Indigenous practices, such as music.

“In labour, your child is to be sung into the world and that it’s something to be celebrated,” Bruce said. “I wasn’t really aware of that. I was just so ashamed that I was a young parent and then going to be a young parent of two.”

Other traditional teachings might include knowledge about traditional medicines, food, smudging and the care of the placenta.

Indigenous culture also focuses on the importance of women having support from their family during delivery.

“Not a lot of family was there to support me with my daughter. I was just alone,” Bruce said.

“With my son, it was more exciting. I was like, ‘OK, this is something to be happy about.'”

Comments