A vow by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau that “a Canadian is a Canadian is a Canadian” is being put to the test as consular officials grapple with how to respond to a request for repatriation by a British-Canadian man imprisoned by Kurdish authorities on suspicion of being a member of ISIS.

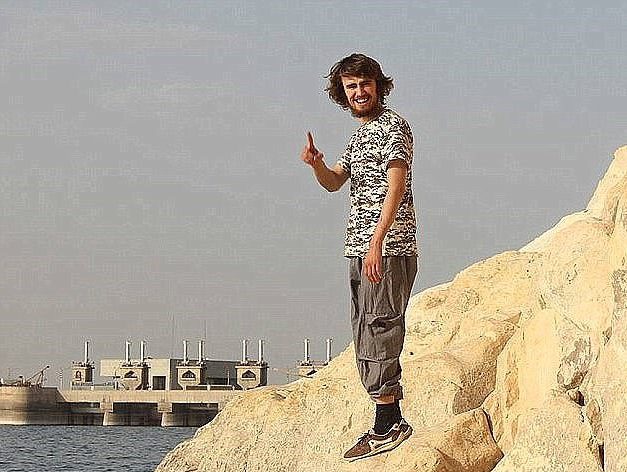

Kurdish forces imprisoned Jack Letts in May 2017 after he left the group’s de facto capital in the Syrian city of Raqqa prior to its fall. His parents have said he was not fighting for ISIS but rather was travelling through Jordan and Kuwait in 2014 before he went to Syria to ‘see for himself what was going on.'”

READ MORE: What happens when an ISIS member returns to Canada? The story of one Toronto-area man

When asked what they are doing on the Letts case so far, British officials have said they are not able to provide consular support to nationals in Syria as there is currently no British consular representation in the war-torn country.

As CBC News reported last week, officials from Global Affairs Canada made contact in January with the man British media have dubbed “Jihadi Jack” and while they have reportedly not given any direct assurance they will be able to free him, they were quoted as saying they are “working to resolve” his situation, raising the question of what exactly could happen if he is freed and comes to Canada.

What are the options? Let’s break it down.

Can he come to Canada and can the government stop him?

Effectively, there are easy answers to both: yes and no.

Canadian citizens have the constitutional right to return to Canada under Section 6 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and attempts in the past by the federal government to impede those who do seek to return have been ruled to be violations of constitutional rights.

Take, for example, the case of Abousfian Abdelrazik.

The Canadian-Sudanese man was detained and tortured in Sudan for six years while visiting family in the African country and was forced to sleep on a cot in the Canadian embassy in Khartoum while officials repeatedly made and broke promises to give him emergency travel documents to return home.

In 2009, the Federal Court ordered the government to repatriate him in a landmark and scathing ruling, and said that by attempting to block his return to Canada by not issuing travel documents, the government had violated his rights.

READ MORE: Government settles with Abdelrazik after ‘grossly unfair’ leak, RCMP still investigating

The government settled in a court case with Abdelrazik in March 2017.

So the question of whether Letts could come to Canada if freed from prison is clear; however, the question of whether Canadian officials have a duty to provide consular assistance is less so.

“The issue of providing consular assistance or not has traditionally been considered a discretionary matter,” said Craig Forcese, a law professor specializing in national security at the University of Ottawa and a frequent witness before parliamentary committees studying national security legislation.

Get daily National news

“The government of Canada can’t block his return in any real way so he can return, at which point the question is, ‘What can they do if he arrives?'”

What are the options?

There are several, not all of them involving charges but all with significant degrees of uncertainty.

First, it is important to be clear that while Kurdish authorities say they have charged Letts with being a member of ISIS, he is not facing any actual charges from Canada or Britain, and his family maintains that Letts did not go to Syria to fight for ISIS.

Second, the issue of prosecuting any individual who returns to Western countries from the conflict in Iraq and Syria has repeatedly proved challenging for authorities, with only two charges laid against Canadians who have returned from fighting abroad.

WATCH ABOVE: How the RCMP deals with terrorist fighters returning to Canada

The reason it is so difficult to investigate and lay charges against individuals returning from war zones contains several factors: among them, a lack of diplomatic presence on the ground in Syria or the lack of reliable information that can hold up — or even be disclosed — in a court of law.

Intelligence collected by Canadian or allied spies is also notoriously difficult to use in court given information presented as evidence in court becomes part of the public record and in some cases could jeopardize either ongoing intelligence activities in the region or reveal more information than officials are comfortable with about exactly how they got the information in the first place.

READ MORE: Fact check: Are Liberals welcoming ISIS returnees to Canada with open arms?

If there is evidence to suggest an individual participated in a terrorist activity abroad, they can be charged under Section 83 of the Criminal Code upon their return to Canada and sentenced to up to 10 years in prison.

Canadians who leave the country to do things like fight or join with ISIS can also be charged with the specific offence of leaving Canada to participate in a terrorist activity.

However, that particular charge would not apply to an individual who could come to Canada after departing from another country to take part in a terrorist activity in a third country or region.

WATCH ABOVE: Suggesting Liberals want to protect ISIS fighters a fabrication: NDP

“Letts could not be prosecuted in Canada for terror travel offences … as he did not leave from Canada to go to the Middle East,” said Wesley Wark, also a national security expert at the University of Ottawa. “But depending on the evidence of his alleged involvement with IS or other listed terrorist entities in the region, he could be charged under the Canadian Criminal Code with a variety of facilitation and advocacy charges.”

If the government were to have evidence that they believed showed an individual constituted a threat but which was not enough to secure a charge or potential conviction, they could also have the option of placing the person on the no-fly list once in Canada to restrict them from going anywhere else.

They could also seek a peace bond, formally known as a recognizance with conditions.

Those are essentially restraining orders in which an individual agrees to keep the peace and to which conditions can be attached such as requirements that the individual surrender their passport, participate in a treatment program, observe a curfew, or wear an electronic monitoring device, among other options.

“That too will turn on evidence because you have to prove the fear and the evidence has to be objectively reasonable, it can’t just be a hunch,” noted Forcese.

If that fails, officials would likely be forced to rely on seeking authorizations for surveillance.

What about extradition?

Extradition could also be a serious consideration.

Under U.K. law, similar to Canada, preparing for intended terrorist activities, including attempting to travel, is a criminal offence under Section 5 of the Terrorism Act (2006).

READ MORE: Number of returned foreign fighters ‘essentially the same’ as 2 years ago: Ralph Goodale

If law enforcement in the U.K. were to feel they had enough evidence to pursue charges against an individual they believe left or tried to leave to take part in terrorist activities, they could find it easier to do so than Canada when the departure in question is from the U.K.

“There may be an evidentiary track record in Britain itself as to why he was leaving and what he was planning, in which case you wouldn’t be as dependent on what he actually did overseas,” he said. “That might make things a little bit easier for the British to prosecute because our travelling offence says, [an individual must] ‘depart Canada.'”

Both Wark and Forcese said if that were to be the case, there would likely be little argument for the government to refuse a request for such an individual to be extradited to the U.K.

Forcese noted that the similarities in justice systems and possible charges between both countries mean a U.K. prosecution of an individual in a similar case would essentially fit the “gold standard” Canada sets when evaluating requests for extraditions of its nationals.

“The gold standard for extradition is you can only extradite for something that’s also a crime in your own jurisdiction,” he said. “So if the U.K. had some kind of peculiar terrorism law that wasn’t emulated on some level in Canada, then there wouldn’t be an extradition but based on my knowledge of the U.K., they line up reasonably well.”

Technically, the U.K. could also revoke the individual’s citizenship.

In that case, extradition would not be possible and any potential investigation or charges against them would be solely within the domain of Canadian law enforcement.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.