Lindsey Schweigert found herself in her pyjamas, in the back of a police car in March 2011 and wasn’t sure how she got there.

According to a report in Marie Claire magazine, she had arrived home exhausted that evening, taken a generic Ambien and fallen asleep around 6 p.m. But she didn’t stay in bed – she got up around 8 p.m., drew a bath, and left the house with the water still running. She then got into her car to pick up some fast food.

She drove into another car, and police arrested her for impaired driving. She said the only thing she had taken that evening was Ambien. She later pleaded guilty to careless driving – a lesser offence.

In 2000, 15-year-old Vanessa Young suddenly suffered a cardiac arrest in her home and died later in a Hamilton hospital. She had been prescribed cisapride for stomach complaints. According to a coroner’s inquest into her death, she died “from the effects of bulimia nervosa in conjunction with cisapride toxicity and possibly an unknown co-factor such as congenital heart defect.” She had been prescribed the medication while also having bulimia, something which the manufacturer said it had informed doctors not to do.

While these two cases might appear to have little in common, both women had taken drugs that later research indicated had different effects on women than men. And although we don’t know whether sex differences had anything to do with why these two women in particular suffered, doctors say that there’s a lot we don’t know about the different effects that drugs can have on men versus women.

The reason is simple: researchers just haven’t historically studied women as much as men.

After high-profile scares like thalidomide in the 1960s, where pregnant women taking the drug had children with serious birth defects, drug researchers were hesitant to include women in drug trials because of the possibility that they might get pregnant, said Dr. Cara Tannenbaum, scientific director of the Institute of Gender and Health at the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

“I think it was well-intentioned at the time that women be excluded from drug trials because of the unintended effects on a fetus of a drug that hadn’t been tested for safety yet.”

Also, women’s menstrual cycles were seen as a complicating factor in drug trials. Generally, researchers want to keep as many variables as they can the same, to get a clearer picture of what effect a drug is having. Fluctuating hormone levels can affect how drugs are absorbed by the liver, said Tannenbaum, so it was simpler to just test on men, who didn’t have this issue.

It even goes back to lab rats.

“The majority of drug development research is still done in male-only animals,” she said. Aside from questions about hormones and the estrus cycle in research animals, there were more practical considerations — like ending up with more rats than you started with.

Get weekly health news

The male and female rats’ hormones would spike, she said, and they’d be having “fun” and get pregnant, “so historically it was just easier or perceived as being simpler to do the experiments in only males.”

So for decades, women weren’t adequately represented in drug research, she said.

“Fast forward 10, 20, 30 years from the 1960s and what happened is all of the big drug trials, in this case for the cardiac drugs and other drugs, were having trials where very few women were included.”

This started to change with the American Federal Drug Administration issuing research guidelines in the 1990s, encouraging researchers to include women. It’s gotten better since then, said Tannenbaum, but still has some way to go before drugs are tested on populations that better reflect who might use the drug in the end.

For Dr. Paula Rochon, vice president of research at Women’s College Hospital in Toronto, the bigger issue right now is how results are reported — whether sex and gender differences are even analyzed.

“It’s not just the representation, it’s the reporting,” she said. “People may be included in clinical trials who are women and men but that information is not specifically reported in a way that it’s able to be used.”

All of these gaps have had serious consequences.

Asleep at the wheel

Take Ambien — as so many people do. Five per cent of American women reported taking a sleep aid like Ambien in the past 30 days, according to a 2013 study by the National Center for Health Statistics.

In 2014, the FDA recommended cutting in half the dosage prescribed to women. The reason? There were 700 reports of car crashes and driving impairment related to the drug.

Following those reports, the drug monitor obtained new research on how much drug was still present in patients’ blood the next day. It turned out that women didn’t process it as quickly as men, and they were still impaired in the morning as they drove to work or their kids to school. The manufacturer had already warned consumers and doctors about the risks of impaired driving with the drug, but the FDA wanted to make the next-day risks even more clear.

“The reason it causes car accidents is because it decreases your concentration and attention. So you could also fall and break your hip. Or hit your head and get hospitalized and never make it back home again,” said Tannenbaum. For these reasons, the FDA changed the prescription guidelines for the active ingredient, zolpidem — a change that was also made in Canada.

There are some other drugs that have sex-specific dosing guidelines or that are only prescribed for one sex, according to the FDA, but neither they nor Health Canada could say how many there are.

A study done by the United States General Accounting Office in 2001 found that of the 10 drugs withdrawn from the market since 1997, eight posed greater health risks for women than men. Some were because women were more likely to take the drug in the first place (like appetite suppressants, for example) and some were because of biological differences between the sexes. Some of these drugs, like cisapride, prescribed for stomach problems, have deadly side effects in some women. In cisapride’s case, in some circumstances it affected the heart and led to arrhythmia, according to the GAO.

Biological differences

Everyone knows that men’s and women’s bodies are different. But some differences are less obvious than others.

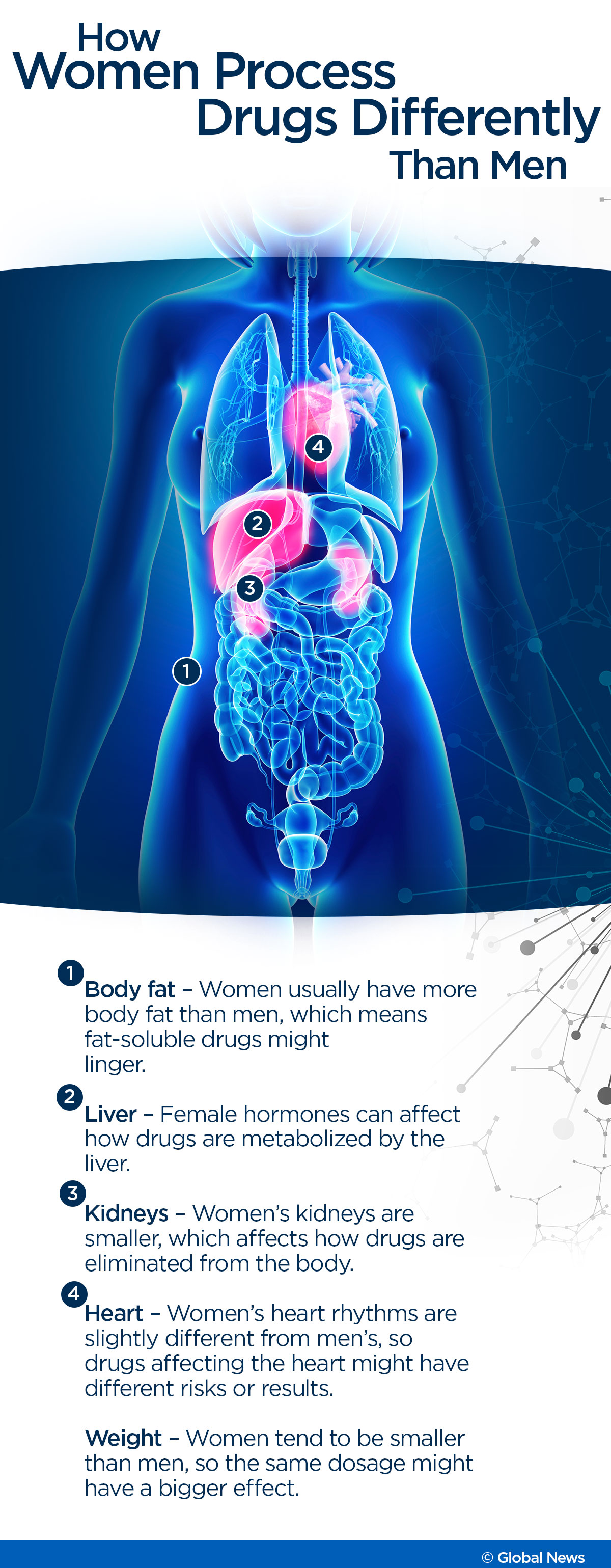

Sleeping pills like Ambien are often fat-soluble, said Tannenbaum, and because women tend to have more body fat than men, such drugs might remain in the body longer. Women’s heart rhythms are also different, she said, so drugs like cisapride that predisposed people to arrhythmias could harm women more.

Female sex hormones can affect how drugs are processed by the liver, she said, and women’s smaller kidneys can mean that they eliminate drugs more slowly from their bodies.

“To me it’s always been so fascinating that you walk into a clothes store and of course men have the men’s section and women have the women’s section. Yet when it comes to health and drugs, why isn’t there a men’s section and a women’s section?”

If their bodies are different enough that they wear different clothes, why not drugs too, she asks.

There are non-biological differences as well, said Rochon. Women live longer than men, so it’s especially important to test drugs’ effects on senior women. Women tend to have more chronic conditions too, and are more likely to take medications — and more medications — than men, which could put them at risk of drug interactions.

Historically, drug trials tended to be on younger, healthier, more male populations, she said. “But the reality is that a lot of the drug therapy use is by people who are older and in the older age groups more likely to be women, and have multiple issues, medical problems going on.”

“So we often don’t know as much from a clinical trial as we might want to know about how best to use that therapy in a larger population setting.”

The Women’s College Hospital has a program to help medical researchers design their trials with gender differences in mind, she said. And researchers are also beginning to look at data on existing drugs, to determine whether they have different effects on men and women.

With decades of research to go through, it’s a big task.

In the meantime, Tannenbaum recommends that women who are prescribed a new medication ask their physicians about whether it was tested on women or people of their ethnic background. The FDA’s Drug Trials Snapshots website provides easy-to-understand information on all drugs approved since January 2015.

Patients should trust their doctors’ expertise, she said, but she believes it’s important to ask questions.

Comments