On our drive from Calgary towards Fort McMurray, Global News photographer Dani Lantela and I didn’t know what to expect. We had seen the horrifying pictures, and spoken to our colleagues covering the wildfire from the beginning, but we also knew the winds of the story had changed, and our access would be quite limited.

READ MORE: Global’s ongoing coverage of the Fort McMurray wildfires

We saw some abandoned vehicles along Highway 63 heading toward Fort McMurray, but for the most part we couldn’t see too much smoke. We finally reached the roadblock at around 9 p.m. The television crews had left for the evening, and the police officer who greeted us at the roadblock was very helpful, but also very tired. He was on hour five of a 12-hour shift, and it looked like he hadn’t slept very well in a week. I asked him if he wanted a Red Bull, and he was guzzling it by the time the question left my lips.

A truck filled with supplies pulled over on the other side of the road, so we went over to chat. A man named Daryl was in the back of the truck and he told us he drove all the way from Saskatchewan to help out, picking up supplies and a few other people along the way. No one had asked him to come, he just felt compelled to help out when he saw the images that were circulating across Canada and around the world.

READ MORE: Alberta government releases new app showing Fort McMurray wildfire damage

He said he just camped out at different locations in the area, seeing if anyone needed anything. He brought water to officers, gas to some stranded drivers, even a pair of shoes to a young man at an evacuation camp. He offered water and warm gloves to our crew, but we had just got there and knew there was a long line of workers and evacuees who needed it much more than we did.

After our live report updating the fire, we said goodbye to the officer and made our way to the Mariana Lake Lodge, about an hour south of the roadblock. It was an open camp that housed oil workers, which we found out became a safe haven for families in the hours and days after the evacuations.

It was about 12:30 a.m. when we finally got to camp. We were met by an over-caffeinated and very helpful security guard named Klaus who showed us to our rooms. Later that week, when more RCMP officers showed up, Klaus gave up his own room for them and told the receptionist he would sleep in his van.

“Just give me five minutes,” Klaus said, and quickly scurried off. I asked him for an interview the next morning, but he refused. He said he wasn’t interesting enough and had a face for radio. I disagreed, but Klaus wouldn’t budge.

The next morning on our way out to the roadblock we saw a man on the phone, in front of an army of RVs in a small pullout area. We pulled over to chat to him, and he told us he had been sleeping there for the last five nights. He was from Fort McMurray, and owned a construction company in town. He was told that his equipment was untouched, and now he wanted to go back inside to help rebuild.

Get breaking National news

Many of the guys on his crew had lost homes in the fire, and he thought it would help with the healing process. Throughout the day we heard similar stories to that effect: people who wanted to go back into town to help, but missed the deadline to sign up. It turns out the government does have an emergency number specifically for those people, and a lot of them called or texted us to say they did eventually get inside. Once they were in there, they understood the reason for the delay.

Displaced residents can call the 24-hour emergency line at 310-4455

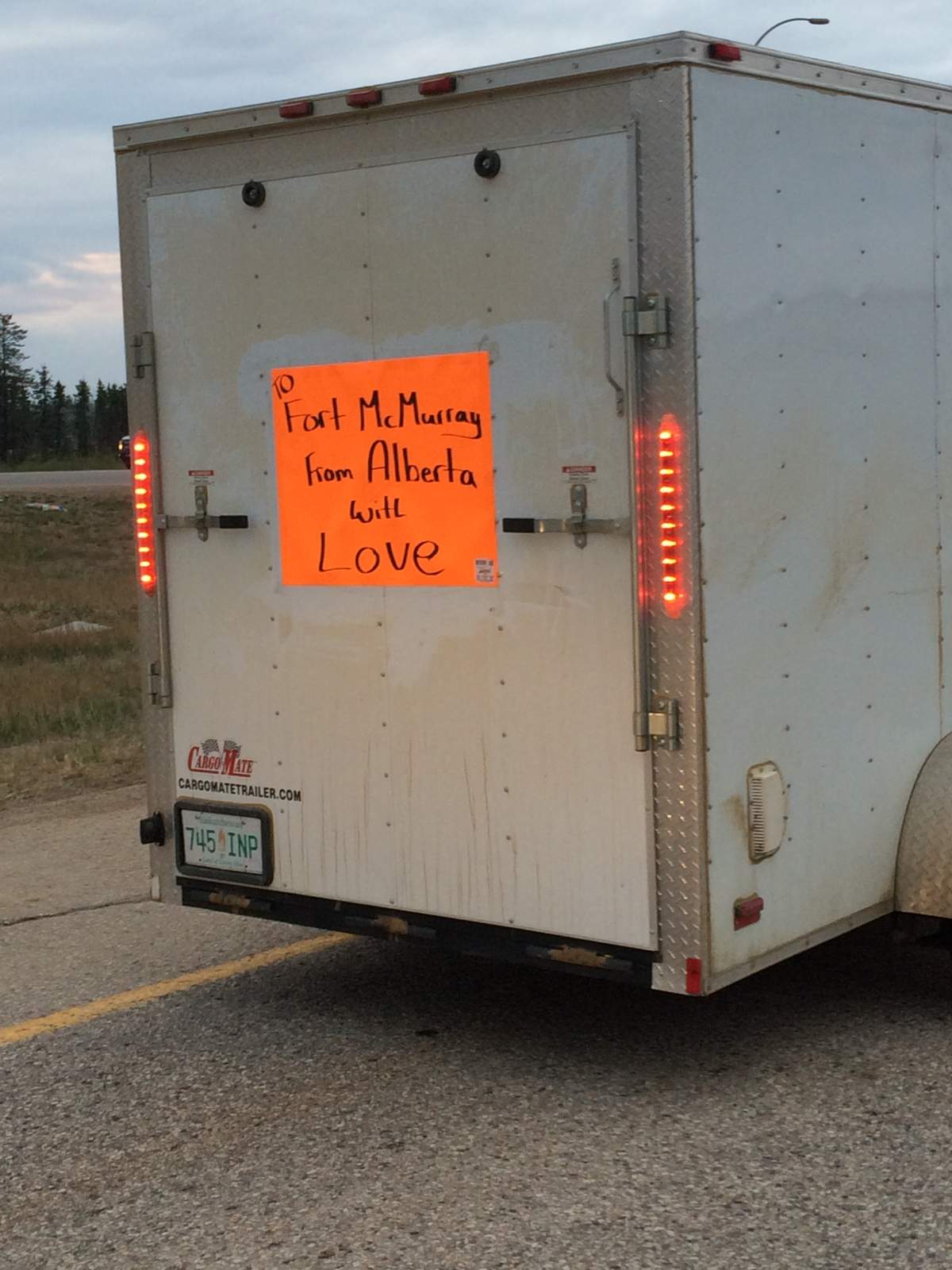

We met a lot of people over the five days, and each story seemed to tug on the heartstrings a little harder. Truckloads of people and equipment came in to help, and T-shirts were passed around, with “Fort Mac We’ve got Your Back’” written across them.

One story that really stuck with me was Jeremy Hall. Jeremy was a big, strong motorcycle rider with tattoos covering every area of his arm. He was a volunteer firefighter from Grande Prairie who had a lot of friends in Fort McMurray.

When some of the stories started to trickle in, he knew he had to help. Jeremy put together a team to collect supplies and came to help his brothers and sisters on the front lines. We were interviewing Jeremy about the process of getting a permit to go inside, when the conversation moved to the carnage behind the blockade. He painted an apocalyptic picture for us, and started to get emotional when speaking about trying to save homes. It hit him the hardest when he saw a little girl’s picture on a burning wall. He said it reminded him of his family back home:

“This can just as easy be any of us.”

WATCH: Emotional interview with Jeremy Hall

On Thursday, the smoke started to hover over our heads, and hot spots started to flare up in the forests around us. The steady stream of water bombers would come overhead, but we were assured the threat in the city itself was over. That same day, Fort McMurray Fire Chief Darby Allen came to the checkpoint to announce he was handing over operations, as the threat was no longer imminent.

We’ve all witnessed his deserving rise into hero status, and marveled at his calming nature, but what really stuck with me about Darby was when the cameras stopped rolling. He didn’t just shake hands with his team; he gave each of them a big bear hug. No matter what their relationship at the beginning of this ordeal, they are now bonded forever, as family.

WATCH: Fort McMurray Fire Chief Darby Allen’s emotional press conference

My favourite story from Fort McMurray, however, came from a team of oil workers we tracked down over social media. They call themselves the Rough Riders, and they work various jobs at the Syncrude site north of town. Twelve guys from around the country—a maintenance guy here, a safety inspector there—all evacuated during the fires.

While many of their coworkers headed home, they asked how they could help. There was a need for water truck drivers since the hydrant systems in town were destroyed. These guys took this job seriously, and became an important piece of saving the hamlet of Anzac when they refused to leave the side of the fire crews.

Ryan Polak, an Edmonton firefighter, told me that without their help, much of Anzac would have been destroyed. He called the team heroes, but was cautious when I reached out to him for an interview. After I assured Ryan the story was going to be about the guys, and not about him, he obliged.

“This is what I get paid to do, it’s my job,” Polak said. “These guys did this with no training to save a town they’re not even from.”

WATCH: Oil workers pitch in to help save Anzac

We went up to Fort McMurray to cover a fire, or at least the lingering firefight. To be perfectly honest, we didn’t get all that close to the flames. When it was time to leave, I was somewhat disappointed we couldn’t get access inside to tell the stories of rebuilding the city. However, on the long drive home, I realized that wasn’t the story that needed to be told.

I learned during the 2013 floods that when times get tough in Alberta, the people of this province truly step up. It’s not an, “I’m glad that’s not me” mentality, but rather, “What can I do to help?” As Jeremy Hall said, this could have been any of us; any town, any of our homes.

The days, weeks and months ahead are going to be long and hard for so many people up there, but right now the people of Alberta are giving them a huge Darby Allen bear hug, and telling them—no, promising them that it’s going to be OK.

That’s the story right now—that’s the feeling of the entire community. We do have your back Fort Mac, because we’re going to need you to have ours somewhere down the line.

Comments