WATCH ABOVE: Why does California’s drought matter for Canadians?

When the water hole dries up, the saying goes, the animals look at each other differently.

California’s water crisis, which is much more far-reaching than something that could just be described as a drought, is as good an illustration as any.

There is a drought, certainly. California has had little rainfall, or snowfall to renew the mountain glaciers that fill the state’s rivers in better times, since 2012.

California’s vanishing snowpack

Between January, 2013 and January, 2014, snowpack in the Sierra Nevada mountains virtually disappeared. The Central Valley, California’s farming breadbasket – and source of much of Canada’s fresh produce, especially in winter – looks much drier in the 2014 image.

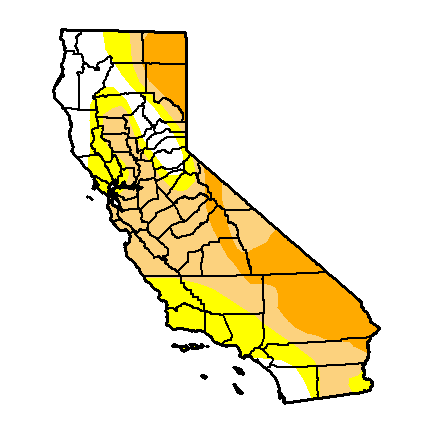

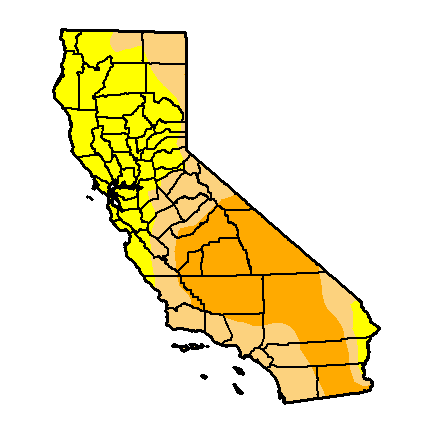

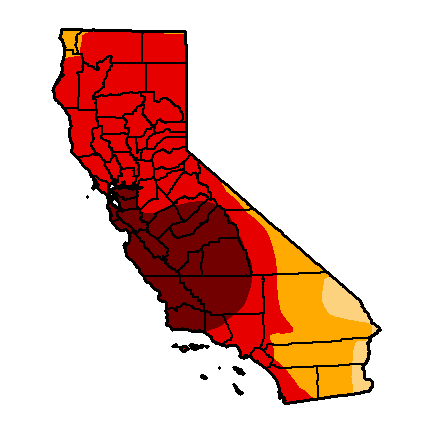

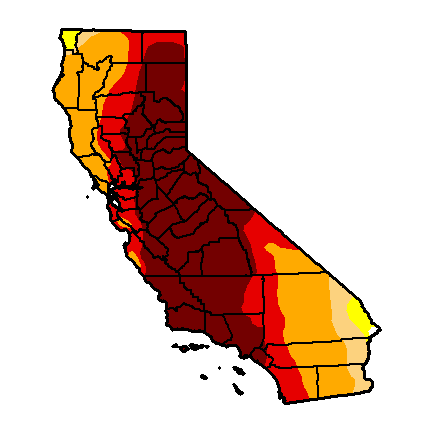

Four maps show how California’s drought has worsened year by year. The dark red indicates ‘exceptional drought,’ the worst possible status.

April 24, 2012 | April 30, 2013 |

May 6, 2014 | April 28, 2015 |

Without rain or river water to draw on, it’s tempting to turn to well water to keep farms green and profitable.

But many writers turn to the image of a bank account – without deposits of rain and river water, wells will sooner or later run dry, as the aquifers empty. Drought accelerates the problem – while well water supplies 29 per cent of California’s water needs in a normal year, that rises to 39 per cent in a dry year and 60 per cent in a drought year, a Stanford University study shows.

The withdrawals are of deposits made a very long time ago: some water being pumped from deep wells in California is 10-30,000 years old, a legacy of the last ice age.

And as water is taken from the ground, it sinks. In the fertile San Joaquin Valley, researchers found an area that had sunk 54 centimetres in a two-year period, as water levels in local wells fell.

Drained aquifers become damaged and lose the capacity to store water – even if a rainy period were to return in future years, the aquifers might not be able to refill to hold the amount of water they did originally.

Changes in California groundwater levels, 2004-14

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES

READ MORE: Your Food

A recent University of California, Davis study showed the impact the drought has already had on the state’s agriculture: over half a million acres taken out of production, 18,600 jobs lost, US$2.7 billion lost to California’s economy, and more and more dependence on pumping groundwater to keep the remaining fields in operation.

“This study does not address long-term costs of groundwater overdraft, such as higher pumping costs and greater water scarcity,” the authors warn. “The socioeconomic impacts of an extended drought, in 2016 and beyond, could be much more severe.”

Running dry: California’s water crisis in photos

As if that wasn’t bad enough, scientists warn that dry conditions may be both the new normal, and the return of an old normal. Archaeology shows that California has endured century-long dry periods at times in the last 2,000 years. What if, in the long run, it’s rain that’s California’s exception, and drought that’s the norm?

“The mean state of drought in the late 21st century over the Central Plains and Southwest will likely exceed even the most severe megadrought periods of the Medieval era,” the study’s authors warn.

“Combined with the likelihood of a much drier future and increased demand, the loss of groundwater and higher temperatures will likely exacerbate the impacts of future droughts, presenting a major adaptation challenge for managing … water needs in the region.”

(A lack of accurate information about water use and a seniority-based water rights system, now being aggressively criticised, don’t help conservation efforts.)

California’s crisis and Canada’s food security

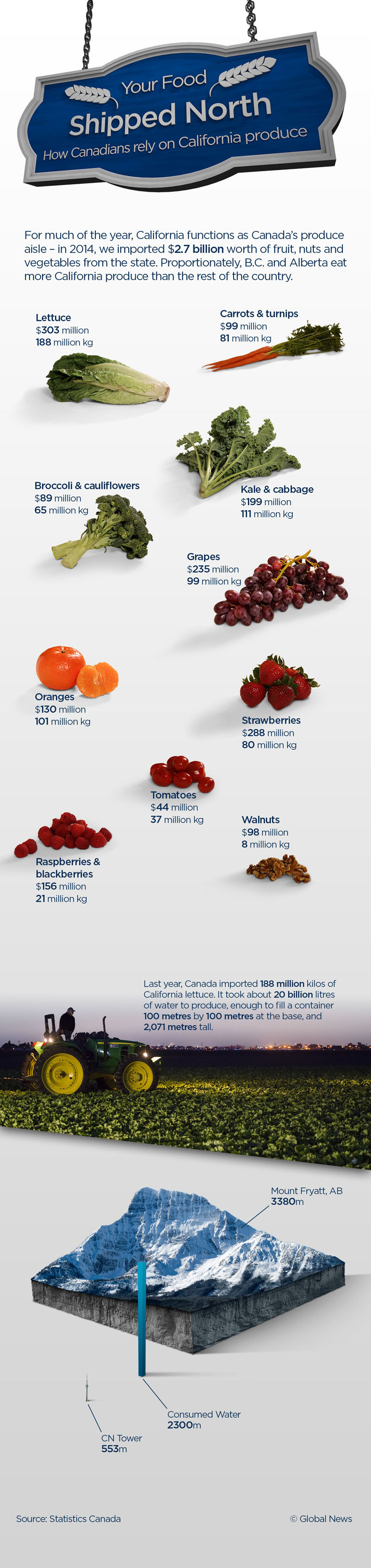

For years, Canadians have been eating their share of California’s apparently endless abundance. California farm products, mostly vegetables but also nuts and fruit, feed millions of Canadians. Last year, Canada imported C$2.7 billion worth of California produce, or 1.2 billion kilograms of everything from figs to persimmons.

The West is more dependent on California produce than the rest of Canada – California is Alberta and B.C.’s top state for fresh American tomatoes, for example, while in much of the rest of the country it’s Florida.

So what does it mean for Canada if, or perhaps when, California’s agriculture fails, at least to the extent that the state can’t export food on the same scale?

For much of the year, California functions in large part as Canada’s produce aisle. 84% of our imported celery comes from California, for example.

We will certainly see higher prices for winter vegetables, explains Sylvain Charlebois, a business professor at the University of Guelph.

“In the last few months there has been a significant jump in lettuce prices – tomatoes as well. Nuts,” he says.

“All of these products we import a lot from California. So in the time it took to be hard-hit by the drought, coupled with a weaker Canadian currency, and the time it took for food importers to find new, secure suppliers, you saw prices really jump between January and March.”

If the drought became structural, that would become a long-term reality, he says.

“You’ve already seen significant jumps over the past few months, and I suspect that it will just compel distributors to seek the same kinds of products elsewhere. They will have to pay more.”

The worsening drought coincided with a fall in the Canadian dollar, which also hiked prices.

(Grocery chains must buy produce from abroad in U.S. dollars, not only from the United States but also from other countries, like Chile and Mexico.)

“I don’t think it would look different, in terms of the variety of products we have access to.”

“Prices would go up.”

“Prices are going up, but that would become a significant factor, particularly for produce – fruits, for example. You’ve already seen significant jumps over the past few months, and I suspect that it will just compel distributors to seek the same kinds of products elsewhere.”

On the other hand, many factors go into the rise and fall of food prices, says David Wilkes of the Retail Council of Canada.

“Transportation, the cost of gas, the cost of diesel, currency fluctuation. It’s had to make a universal statement that x would be more expensive with the drought that we’re seeing in California. There are too many variables, and it also depends on the trading partner relationships and business relationships that individual members have with their suppliers.”

For years, California has supplied cheap food produced in a First World environment, with an advanced country’s food safety standards. Sourcing more food from the developing world, Charlebois warns, may raise safety issues that we don’t see now to the same extent.

“As soon as you get out of North America, or into Mexico, for that matter, things get a little more complicated.”

“You’ve got language issues, you’ve got resource issues. Obviously, developing countries don’t have the same amount of resources to monitor properly, to mitigate risks properly.”

“Obviously you don’t want to import products from abroad that don’t comply with our own certification standards. When it comes to produce and vegetables and fruits, the last thing you want is a major product recall from Mexico, or other places, that may affect consumer confidence.”

Wilkes rejects that argument.

“It’s a foundational commitment that we make to our customers that the products that we source, and put on the shelves of the store, are safe. Where the product is sourced does not change the rigour with which the food safety standards are applied by grocery retailers across Canada.“

“Members will conduct audits, members will conduct visits – it’s a responsibility that’s taken very seriously.”

READ MORE: Food safety

Moving food production further south creates new and unsettling issues, however.

Canadians’ and Americans’ insatiable demand for avocados meant prosperity, at first, for farmers in the southern Mexican state of Michoacán.

But soon, the Templarios, a ruthless and very violent gang involved in the drug trade, started extorting payments from avocado (and lemon and lime) growers. The Templarios kidnapped and murdered farmers’ children, and forced the sale of farms at prices of their choosing.

One lemon grower was given an offer he couldn’t refuse, Nexos, a Mexican magazine, reports: the Templarios said they would buy his farm for the price that they named, and his only choice was whether the money would go to him or his widow. (Open link in Chrome for translation.)

When the farmers had had more than they could endure, they formed a militia to fight back, which the Mexican federal government (after clashes that left several people dead) is now helping to arm and organize.

The force is funded in part by avocado growers.

In March, after a recent series of arrests, which seem to have drawn the gang’s teeth, at lest for now, an Al Jazeera reporter in Michoacán found residents much more willing to speak openly about what the conflict had been like. They described a years-long-reign of terror that included midnight abductions by death squads and terrifying roadblocks manned by heavily armed men high on marijuana.

In photos: Inside Michoacán’s bloody rural conflict

In 2014, over 80 per cent of Canada’s avocado supply came from Mexico; Michoacán produces 85 per cent of Mexico’s avocados.

A long-term drought in California may mean new markets for Canadian farmers.

“There would be some good opportunities for Ontario,” predicts Mark Wales, an Aylmer, Ont. farmer who is a board member of the Ontario Federation of Agriculture.

“What you’ll see is a gradual relocation of some crops, potentially to Ontario.”

“But I would say that the greatest opportunity is for something like paste tomatoes, which we already grow here. We have a history of doing it, and good quality and yield, and we do have the available water.”

(Ontario’s processed tomato industry, based in the province’s southwest, has seen better days. Last year, a large tomato processing plant in Leamington, Ont. was saved from closure when Heinz sold it to food processor Highbury Canco. The plant is still in production, though with a smaller workforce at lower wages, and fewer farmers with supply contracts.)

“Garlic is something we could grow a lot more of here – we’re growing a pittance of what we could grow.”

But climate limits Canadian agriculture in ways that aren’t going away, he cautions.

“Clearly, we’re not going to start growing almond trees here.”

“We’re also not going to start growing fresh fruits and vegetables outdoors in the winter. So those opportunities aren’t there. Can the greenhouse sector replace some of that product? Certainly.”

Farming in B.C. could expand, though the province has unique land constraints, says Rhonda Driediger, a Langley-area berry grower and packer.

“There’s so much pressure on the land here, making it so high-priced, that it’s difficult,” she explains.

“More land would go into production, but it would probably be with existing farmers. They would be the ones that would afford it. That’s another problem: you can’t expect two 25-year-olds to be married and having their first kids and go out and buy a 40-acre, or even a 10-acre parcel. It’s just prohibitive.”

“There are movements out there to get land that’s fallow right now back into production. There’s a huge cost to that, too.”

Driediger is on the board of the B.C. Agriculture Council.

A long-term drought in California could spur an increase in B.C. berry production, she predicts.

“Berries are probably the easiest. Strawberries, raspberries, blueberries. They have a defined market. If you’re growing them you can sell them easily.”

“It’s not going to mean anything for farmers on the prairies,” Wales says. “It’s not going to mean anything for large-scale grain production. Canola, wheat, barley, the prairie crops, it’s not going to change anything for them.”

Driediger is eying an East Asian market for B.C. blueberries:

“China has a massive need for clean, healthy food. The Chinese public, especially the middle class, is demanding food that is not contaminated. Even if it isn’t contaminated, they want to be sure that it is not contaminated.”

(Four out of five of California’s blueberry export destinations are East Asian countries: the other one is Canada.)

Wales and Driediger agree that a shift away from food production in California would happen slowly:

“If there was a total collapse it wouldn’t happen overnight – it would be gradual,” Wales says. “You will see it coming.”

Comments