A new international study led by Ontario researchers is showing promise in potentially curing HIV. If it makes it through human clinical trials, it has the potential to cure millions of people worldwide, researchers say.

Approximately 95 per cent of people with HIV have it chronically, which Ryan Ho, a master’s student at Western University in London, Ont., and co-first author of the research, said can be defined as having the virus untreated for around one year. Ultimately, this causes a slow destruction of the patient’s immune system and can lead to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Worldwide, 39 million people are infected with HIV, 30 million of whom are on a cocktail of drug treatments. There are side effects and problems with these treatments, mainly that individuals need to be on them for life.

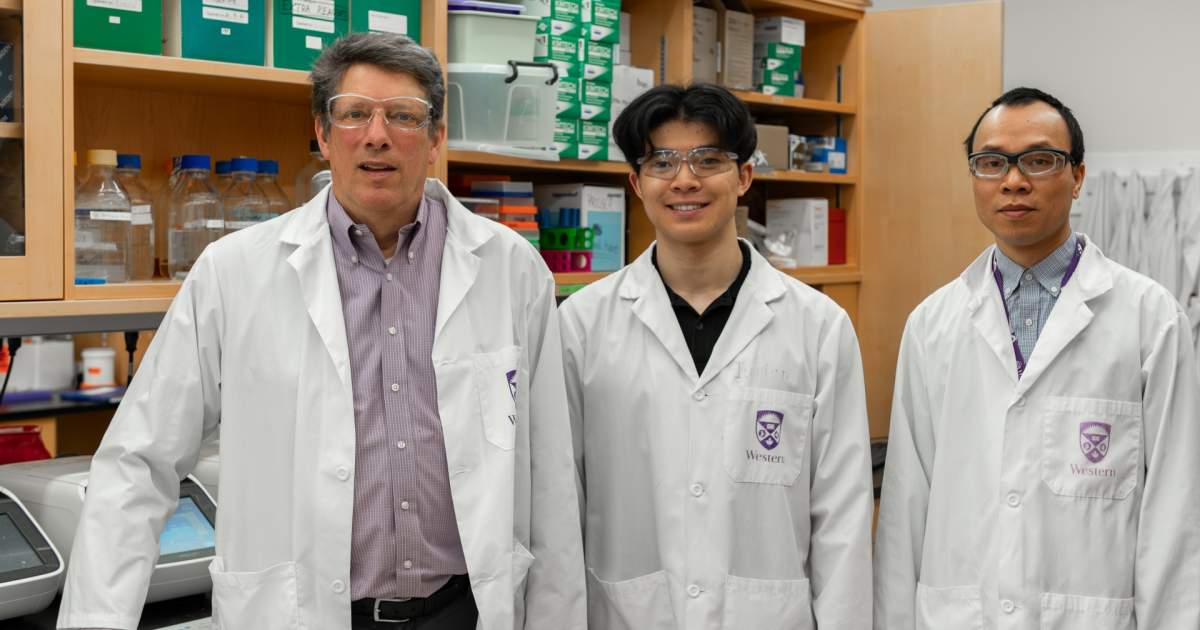

“There’s this small amount of HIV that hides itself in their body, and when you take off the drugs that virus can rebound,” says Eric Arts, professor at the Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry at Western University and Canada Research Chair. “There’s been this goal in the HIV research field for years now to try and find something that will tickle those last few cells that have HIV to release the virus so it can be killed.”

In this new study, led out of the Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, their therapy has shown the ability to drive out the last remnants of HIV in blood samples of those with the virus.

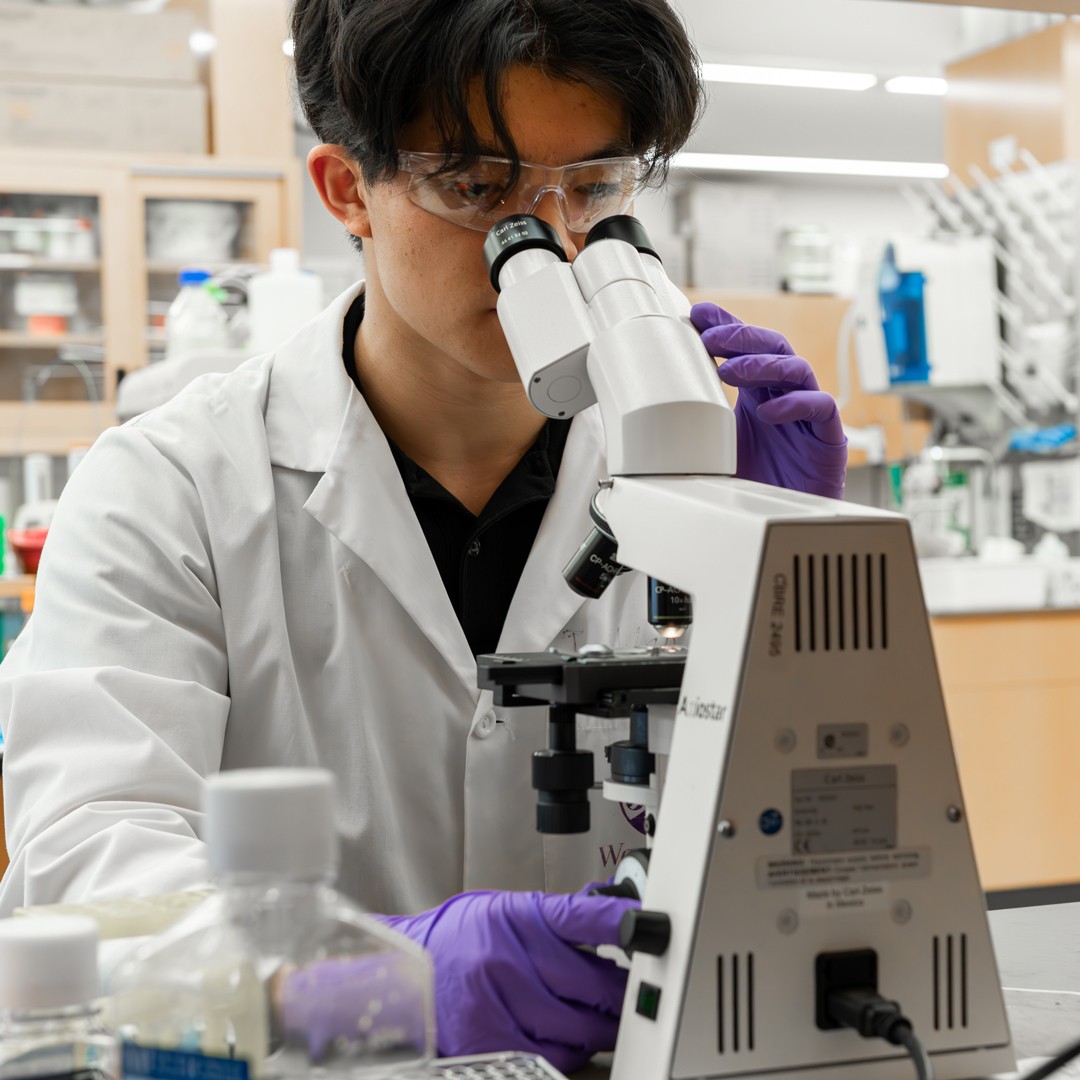

“We acquired blood samples and applied our HIV virus-like particle, or HLP for short,” Ho says. “One other thing we’re looking for is if our HLP, after we apply it to the immune cells, can we detect the HIV virus releasing from these immune cells by measuring the DNA output? That’s something we were able to show.”

Get weekly health news

The first indication that this was an effective treatment was its previous success on blood samples of people who received treatment very early in their infection, but less than one per cent of the 30 million people currently in treatment began it within three months of infection.

The researchers then recruited about 50 people living with chronic HIV who had been on the current standard treatment for a significant amount of time and obtained blood samples. The researchers’ HLP treatment was used on the blood samples very similarly to how it would be given as an injection to patients, and they discovered it was a highly effective way to drive out and kill the remaining amount of virus in their blood.

“It’s very targeted, and we found out that it’s about 100-fold more effective than anything that has been tested before,” Arts says. “We could not see virus anymore that would be present that might cause them problems in the future.”

The next step is to ensure that the treatment is safe enough to move on to human clinical trials.

Ho says one of the most direct takeaways from the research is the ability to reawaken the latent HIV that hides in the immune cells of people who have been adhering to other treatment for many years.

“Us being able to acquire blood samples from people who had been taking treatment consistently for over a decade for a couple of them, and still reawakened this virus, it’s a hopeful takeaway,” Ho says.

The study was not without limitations, however. Researchers were unable to test its effectiveness in those with the C subtype of HIV, which is predominantly found in Asian continents, some of Europe and the Middle East. But subtype C is the largest proportion of the virus that is circulating.

“Targeting C and ensuring that the HLP is effective would be really representative to the existing world’s infection state,” Ho says. “Our project is an international collaboration, but those are predominantly in Uganda, in the United Kingdom, in Cleveland, and somewhere around Maryland, Baltimore, and Toronto, Ont. That’s just due to the collaborations that we have with other professors and other doctors.”

Ho says this logistical limitation is something the researchers plan to address moving forward, as it is simply an access limitation and can be corrected after various approval steps are completed.

“You can’t just acquire people’s blood,” Ho says. “There’s ethics, red tape to cross, consent forms to sign. But this (study) opens the door for that a lot easier.”

For Ho, the preventive approach on the other side of this project is equally important. Bringing attention to, promoting awareness of and preventing HIV acquisition by promoting safe sex and harm reduction are another key focus in ending the epidemic.

“One thing that I’ve gotten involved with in London is the Regional HIV/AIDS Connection where we focus on harm reduction kits,” Ho says. “People will use their substances, but we only we hope that they don’t also acquire seven different viruses by using their substances.”

David Cummings, manager of community relations at the Regional HIV/AIDS Connection, says this development is nothing short of groundbreaking. If successful in clinical trials, Cummings celebrates the significance of the research and that the therapy could offer millions of people living with HIV a cure.

“Today’s treatment options already allow people living with HIV to lead long, healthy lives,” says Regional HIV/AIDS Connection Executive Director, Martin McIntosh. “This progress represents yet another monumental leap forward in our collective response to HIV/AIDS.”

Comments