TORONTO – As countries around the world choose to bury nuclear waste as a containment method, they’ll need to make it immune to decay, future ice ages and tectonic shifts. But the trickiest part may be keeping people out: How do you communicate the dangers of what’s buried beneath the Earth’s surface to people 10,000 years in the future?

Known as “Deep Geological Repositories” (DGR) these mines located 500m to 1000m underground are used in Finland, Sweden, the United States and being considered by more than seven other countries as a solution to storing toxic, radioactive waste.

In Canada, Ontario Power Generation is in the process of applying for a license from the federal government that would permit it to bury 200,000 m³ of low- and intermediate-level nuclear waste 680 metres underneath the Bruce Power nuclear plant located fewer than 2 km from Lake Huron nestled in the heart of cottage country.

Low-level and intermediate nuclear waste consists of anything that comes into contact with radioactive material (i.e gloves, mops, filters, chemical sludge), while high-level nuclear waste consists of spent nuclear fuel.

One problem when burying nuclear waste, known as “human intrusion,” is creating the proper site markings or signs to prevent future generations from accidentally uncovering the radioactive material.

Peter C. Van Wyck, a communications professor at Concordia University, says that one challenge of creating warning systems for future generations is that current universal signs rely on shared understandings, like a symbol of a male figure used to distinguish a male washroom.

“At a basic level, signs that are understandable independent of language rely on shared contextual and cultural conventions. A bathroom sign in Dubai is generally equivalent to one in New Mexico,” he said in an email to Global News.

“Highway signs tend to look similar in different national contexts. Prohibiting signs (something with a cross through it), are typically understood without a grasp of the linguistic community from which it arises,” he said.

Van Wyck says a number of hurdles could arise like global environmental disasters or a loss of archival knowledge due to war that would make it difficult to create warning systems for future civilizations.

In 2007, the International Atomic Energy Agency created a new radiation warning sign using radiating waves, a skull and crossbones and a running person to supplement the traditional trefoil warning symbol.

The new symbol was developed by human-factor experts, graphic artists, and radiation protection experts and was tested by the Gallup Institute on 1650 individuals in Brazil, Mexico, Morocco, Kenya, Saudi Arabia, China, India, Thailand, Poland, Ukraine and the United States, according to the IAEA.

But will this symbol still be understood in the year 12,013 A.D?

At the waste isolation pilot plant in Carlsbad, N.M., the United States Department of Energy has mandated the nuclear facility be secure for a period of 10,000 years.

In the early 1990’s, the EPA convened what was called a “futures panel” comprised of intellectuals from fields like archaeology, anthropology, physics and semiotics to help deal with the problem of “inadvertent human intrusion.”

“From pictogram sequences showing how the site would contaminate humans, to elaborate astronomic maps showing how the precession of the stars could be used to tell when the site would be safe. Everything was considered,” said Van Wyck. “But there was little agreement as to what the key strategy might be that would overcome the problem of language.”

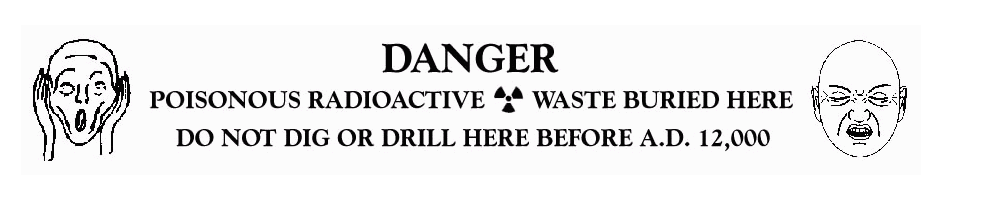

One proposal that did overcome the problem of language, says Van Wyck, suggested using a human face expressing motions like horror, nausea, fear, and pain might provide a basis for a pan-cultural meaning.

The design was based on Edvard Munch’s “The Scream,” and included some early mock-ups.

In Ontario, OPG says decisions regarding site markers for the proposed DGR are still under consideration.

“As part of the environmental assessment site markers have been considered but decisions related to the markers have not been made yet. Those decisions will be made at a later date,” said Neal Kelly, a spokesperson for the OPG. “As we go through those different stages we’ll have to get different licenses and markers will be part of our decommission license for the DGR.”

OPG also says long-term preservation of knowledge through the permanent storage of documents and institutional controls (including signs) consistent with best international practices will be put in place.

Signs aren’t the only thing being done to help prevent future societies from uncovering radioactive mines, said Jeremy Whitlock, a reactor physicist and spokesperson for the Canadian Nuclear Society.

“You’re not supposed to have to depend on institutional controls including signs,” said Whitlock.

Whitlock said that choosing a location with low mineral or natural resource value helps to reduce the inadvertent human intrusion factor, and placing it in stable bedrock that is from a pre-historic era reduces the chances of radioactive gas escaping or contaminating surface water.

“The idea is that once everything is in place you could have an apocalypse or ice age and if basically everything gets erased it would be one spot you wouldn’t have to worry about,” Whitlock said. “You’ve created a uranium mine and you’re just putting the stuff back into the ground. The rock was radioactive to begin with and you’re just adding more.”

Comments