TORONTO – The Ontario Court of Appeal ruling that gives police officers the right to look through a cellphone that does not have a password on arrest is a “huge intrusion” on people’s civil liberties, according to a Toronto area defense lawyer.

The court of appeal ruled Wednesday that it is legal for police to have a cursory look through a phone upon arrest if it’s not password protected, but if it is, investigators need a search warrant.

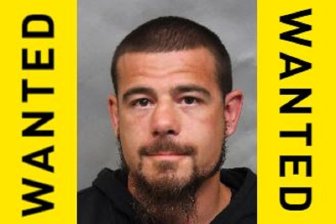

The ruling came after a man appealed a robbery conviction, arguing that police breached his rights by looking through his phone after his arrest.

The court denied his appeal, saying that police were allowed to look through the man’s phone “in a cursory fashion” to see if there was evidence relevant to the crime.

Traditionally, this “cursory” search would occur when police pat down a suspect when they are arrested and find something in their pockets, bags, or on their body.

According to criminal defense lawyer Sean Robichaud, the court seemed to draw the distinction between information that would not be easily accessible to police, including things like personal email accounts. But, what the court seemed to say was that police, in this case, simply entered the phone without a password, looking at texts and phone records and didn’t dig deep into the phone.

“The problem with that analysis in my opinion is that mobile phones are set up specifically so that private information is easily and quickly accessible; that includes emails, phone records and even more in-depth information if you set up applications like drop box or other email accounts that may not be directly on the phone,” Robichaud told Global News.

- What is a halal mortgage? How interest-free home financing works in Canada

- Ontario doctors offer solutions to help address shortage of family physicians

- Capital gains changes are ‘really fair,’ Freeland says, as doctors cry foul

- Budget 2024 failed to spark ‘political reboot’ for Liberals, polling suggests

“I think that analysis that they’ve drawn particularly as it relates to cellphones is largely artificial these days because they aren’t just phones – they are more computers than they are phones.”

But police need a warrant in order to search someone’s computer.

Robichaud notes that issues from this ruling can arise from a generational gap which sees younger generations using their cellphones less like phones and more like personal data devices, or computers.

He argues that although the court’s thinking was that the police weren’t accessing very personal information in text messages, photos, or phone records, that information is highly personal to the user.

“The information that is kept on cellphones these days that’s quickly and readily accessible is often much more private than what people keep locked up in their rooms,” said Robichaud.

Robichaud believes that the ruling is a “huge intrusion” on a person’s civil liberties because as long as the police have a reasonable belief that a cellphone will provide evidence, they can search the phone in this cursory fashion.

“Taking that to any reasonable analysis – there are few crimes that I can imagine where a personal phone, particularly one with advanced technology, wouldn’t afford some degree of evidence,” said Robichaud.

“Practically speaking what this means for police, in terms of their action, is that whenever a person is arrested this will become a matter of course that cellphones will be searched to the extent of they can without using passwords for any further information.”

But legal expert Lorne Honickman argues that we shouldn’t immediately paint a scary picture surrounding this ruling.

“If they wanted to go further, and dig deeper into the data contained on the phone, police would have required the warrant. That was made very clear by the court. In this particular case the trial judge found ‘the expectation of privacy in the information contained in the cell phone is more akin to what might be disclosed by searching a purse, a wallet, a notebook or briefcase found in the same circumstances.’ It seems like good common sense to me.”

What if the police come across some other piece of evidence that can link you to another crime, outside of the one you were arrested and consequently your phone searched for?

According to Robichaud, they would be able to pursue the investigation of that separate crime.

“The police, from my point of view, will justify it on the basis that we felt there was a reasonable connection with this offence and what may have been on the phone. If they discover in the course of the investigation that there were other crimes that were being committed, undoubtedly they would pursue that investigation,” said Robichaud, who noted that according to the recent decision it would be difficult for a defense lawyer to argue that evidence shouldn’t be included.

But Honickman warns against taking implications of the ruling too far: “It is wrong to look at this decision and immediately hop on board the ‘slippery slope’ train and paint a scary scenario about the erosion of civil rights. I understand that many lawyers will be concerned about this ruling and even try to analogize this to a circumstance where if you leave your front door open, police can come in and search. In my opinion, that is taking this ruling way too far,” said Honickman.

He said he would not be surprised if there was an appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada to have a say on the issue.

Comments