Citing the horrors of the tainted-blood scandal of the 1980s, a group of activists and NDP MPs made a public plea on Monday to Health Minister Jane Philpott, asking for an immediate moratorium on paid blood donations in Canada.

The group, led by NDP MP Don Davies, said the recent approval of a licence for a private, paid-donation clinic in Saskatchewan opens the door to many more such facilities, which could compromise the safety and efficiency of Canada’s blood services.

“Profits must never be permitted to compete with safety in our blood system,” Davies said.

“Today, we are calling on Heath Minister Philpott to cancel the license her ministry granted to the paid-donor, for-profit plasma clinic in Saskatoon.”

A moratorium on paid donations would then allow proper consultations to take place, the group argued.

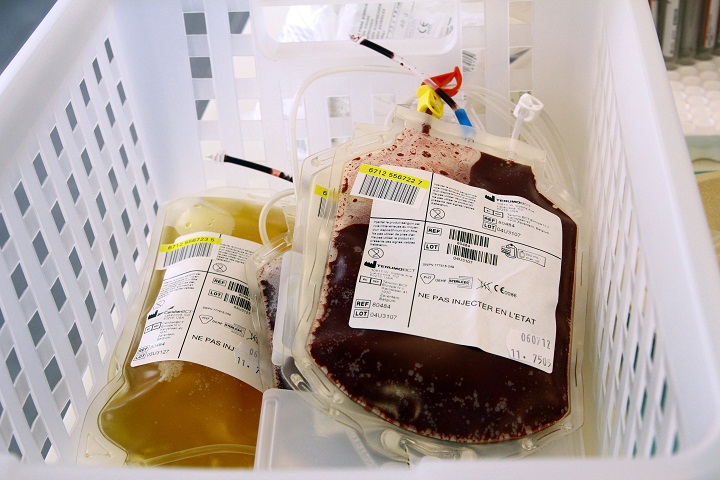

Plasma is the liquid component of blood that holds red blood cells in suspension. After being separated out, it can be used for transfusions or turned into plasma protein products that can — among other things — boost a person’s immune system.

Like whole blood, donations of plasma in this country are just that: donations. With very rare exceptions (one facility in Winnipeg grants honorariums for donations) Canadians are not given any financial compensation for the bodily fluid. But just two provinces — Quebec and Ontario — actually have regulations in place that prevent clinics or private companies from collecting plasma or blood products in exchange for money.

Ontario’s legislation was enacted after Canadian Plasma Resources (CPR), the company that recently set up shop in Saskatchewan, tried to gain a foothold in Toronto and Hamilton.

READ MORE: Controversial plasma collection clinic now open in Saskatoon

CPR has now been open since Feb. 18 in Saskatoon, and says it will give people $25 gift cards for donations. The centre will need to comply with all existing federal safety regulations, screening and testing all its donors. But that’s not enough to re-assure Mike McCarthy, a survivor of the tainted blood scandal who is now living with Hepatitis C.

“They say science is fool-proof, so don’t worry,” McCarthy said.

“There has been no plan presented by Health Canada, nor the Canadian Blood Services, to ensure the public system is not harmed by the introduction of a private, paid-donor model … This is a recipe for another disaster.”

Opponents also argue that paid donations tend to attract and exploit some of society’s most vulnerable populations, including the homeless, drug users and those living beneath the poverty line.

Philpott responded following Question Period on Monday afternoon.

“It’s under the provincial jurisdiction to allow them to open that facility, the role of the federal government is to make sure that the facility is run in a safe manner,” the minister said, adding that plasma products are “entirely safe and of course important for people who need them.”

The notion that paid donors will reduce the number of voluntary donations is “not evidence based,” Philpott said.

Importing paid-for plasma already common

Canada currently collects around 190,000 litres of plasma per year within its borders, which is enough to cover transfusions, but not enough for plasma protein products. As a result, it must import a huge proportion (around 70 per cent) of its plasma protein products from the United States, where paid donation clinics are widespread.

“Unfortunately, the supply does not meet the demand for these plasma products,” said Philpott.

Davies said that practice, in itself, is problematic. Canada should be working to become more self-reliant by improving the public donation system, he said.

“Blood must always be considered a public resource, not a private one for exploitation and profit.”

The Krever Commission

The Krever Commission — struck in the wake of the tainted blood crisis of the 1980s which infected more than 30,000 Canadians with Hepatitis C and more than 2,000 with HIV — recommended against allowing clinics to pay donors for their blood moving forward.

Justice Horace Krever blamed the crisis partly on the blood-collection policies of the Canadian Red Cross, including the importation of plasma from the U.S. that came from unsafe sources.

How plasma is gathered

Plasma can either be separated from the rest of a person’s blood after it is removed from a donor’s veins, or obtained by a process called plasmapheresis, in which blood components are separated as the donation is being made. Only the plasma is collected with plasmapheresis, while other cells recirculate back to the donor.

The second process is less taxing on the body (a person can give plasma by plasmapheresis up to twice a week, as opposed to every 56 days for whole-blood donations), but more expensive, so the public system in Canada gets most of its plasma from whole-blood donations. According to Canadian Blood Services, Canada would need to quadruple the amount of plasma it currently collects in order to avoid importing it from elsewhere.

Comments