Nunavut’s a dangerous place to be a baby: Its youngest residents are more than four times more likely to die before their first birthday than babies elsewhere in Canada.

You’re more likely to die as a baby in Nunavut than as a 70-year-old in the rest of the country.

But infant mortality in Canada’s youngest territory is only the “tip of the iceberg,” says a doctor who’s spent decades researching the health of northern and indigenous populations.

High rates of babies dying indicates there are even more babies getting sick; even more children and adults experiencing negative health outcomes thanks to the same factors putting the youngest and most vulnerable members of the population at risk.

“Infant mortality is just the tip of the iceberg. It’s reflective of the overall health of the population,” says Laura Arbour, a pediatrician, clinical geneticist and professor at the University of British Columbia.

“I can’t emphasize the urgency enough: It has been so long that this has been known as a problem and it has to be understood.

“Why is it so high? And why is it not going down?”

Nunavut has called an inquest into the death of Makibi Timilak, who was three months old when he died in April 2012 in Cape Dorset. But an in-depth study of why babies like him are so much more likely to die is just getting off the ground after years of work.

A review into Makibi’s death found the on-duty nurse mishandled his mom’s call for help, and that proper steps were not followed in terms of designating and investigating the death as a critical incident. The review also found the health centre itself was dysfunctional and rife with bullying among staff.

Makibi was one of 18 babies under one year old to die in Nunavut that year, according to Statistics Canada.

READ MORE: Nunavut calls inquest into murky circumstances of baby’s death

In a vast, remote territory with a small, young population, those deaths loom large.

21.4 Nunavut babies die for every 1,000 live births in the territory. The Canadian average is 4.8.

Nunavut’s infant mortality rate is higher than the national rate of death for Canadians aged 70 to 74, which was 18.5 per 1,000.

- Train goes up in flames while rolling through London, Ont. Here’s what we know

- Budget 2024 failed to spark ‘political reboot’ for Liberals, polling suggests

- Wrong remains sent to ‘exhausted’ Canadian family after death on Cuba vacation

- Peel police chief met Sri Lankan officer a court says ‘participated’ in torture

The mortality rate for male babies is even more stark: 32.3 in Nunavut in 2012 — about six times higher than the Canadian average of 5.1

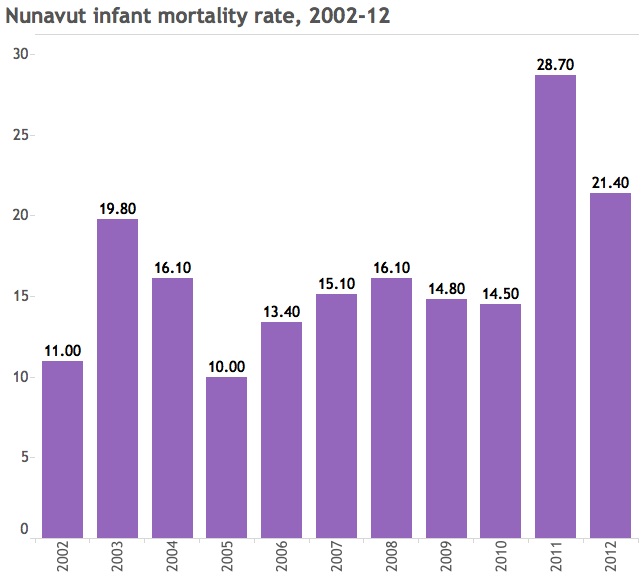

And Nunavut has seen a more significant increase in infant death than any other Canadian jurisdiction: Its infant mortality rate, while it decreased somewhat between 2011 and 2012, had more than doubled since 2002.

Stats for individual years can be misleading on their own, Arbour cautions: The numerators themselves are so small they make for big statistical swings.

But the trendline is scary, she says. The rest of Canada hasn’t had infant mortality rates this high since the 1970s.

“It’s alarming that we’re seeing an increase rather than a decrease, especially over the last five years.”

(The only other provinces whose infant mortality figures went up are New Brunswick and Newfoundland. But neither increased on anywhere near the same scale: About 48 per cent over a decade in New Brunswick, and 11 per cent over that same time frame in Newfoundland.)

And while infant death rates across Canada drop precipitously after a baby’s first day of life, a Nunavut baby’s risk of dying rises again when it’s a few months old.

Those deaths “are considered the most preventable,” Arbour said. So how can we prevent them?

Research into what’s killing Nunavut’s kids — and why they’re dying at greater rates now than a decade ago — is limited.

But there’s a cauldron of complex risk factors: Babies in the north are more likely to be born premature; to live far from medical care and have limited access to health resources; to live in overcrowded, poorly ventilated homes; to be exposed to cigarette smoke either before or after birth.

Genetic variations, even the way babies sleep can play a role.

Makibi’s death was ultimately attributed to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), then revised to a pulmonary infection, then back to SIDS.

In this respect, too, he is not atypical: The plurality of deaths in a 2012 BMC Pediatrics study of infant mortality in Nunavut, which Arbour co-authored, were attributed to either SIDS or Sudden Unexpected Death in Infancy (SUDI), a broader category.

In many of the cases attributed to SIDS or SUDI, sleeping patterns — was the baby on his front? Were babies co-sleeping with their parents? — played a role.

According to the review, baby Makibi was sleeping on his front, with his parents, the night he died — “this was the only position in which he would sleep well.”

In about seven in 10 of the infant deaths studied (where researchers knew how they were sleeping), the baby was sleeping on its front, the study says, “emphasizing the need for improved safe sleep messaging in Nunavut.”

Infection, often respiratory, was the second-leading cause of infant deaths in the study.

That’s a problem that goes beyond infant mortality: Nunavut has a higher hospitalization rate for babies with lower respiratory tract infections than just about anywhere else in the world, the study says.

Genes could also play a role: There’s an association between some infant deaths and a genetic variant, common among Inuit populations, in the gene for CPT1 — a protein used to convert fat into energy that may also play a role in immune function.

We still don’t fully understand that, Arbour says. It’s too early to say whether that genetic variant is itself a risk factor for infant death or an indicator of other factors — remoteness, for example, and distance from good health care — that put babies at risk.

We need better data on risk factors both before and after birth, the 2012 study concluded; and better care for, and education of, moms– especially young ones, of which Nunavut has a disproportionate amount.

“Information regarding sleep position needs to be better communicated in a culturally-appropriate manner. Messaging about infant care and sleep practices should come from within communities as well as from health care providers.”

Arbour saw Nunavut’s neonatal care system up close for the first time as a medical resident doing her placement in Iqaluit in 1992. Since then, she’s been trying to better understand what’s putting the North’s babies at risk, and what that says about the rest of the population.

“We have to understand the whole picture to determine what is happening and why there’s not a reduction,” she said.

Arbour is part of a long-awaited study that will track Nunavut babies to see how they’re doing and what factors make them more or less at risk.

The project will analyze reams of anonymized data — everything from genetics and prematurity to exposures to infections or irritants to post-birth hospital admissions for various ailments will help inform an assessment of the risk factors at play in keeping northern babies healthy, Arbour said.

“If all goes well we will do this project throughout the territory and help to truly understand what is going on,” she said.

“Why do children become so sick, so fast? It’s a very important question to be looking at.”

And it’s a question most Canadians haven’t even thought to ask.

“Infant mortality is not something that people talk about a lot in Canada,” she said.

“They are not only not aware of it but not aware of the implications of what that really means.”

Perhaps the saddest thing about Makibi’s death is that it was hardly anomalous, Arbour says.

“What we’re seeing in the media right now is one example of the heartache and the tragedy facing so many families.”

Comments