While the effects of El Niño are already being felt around the globe, we haven’t seen the end of it, NASA scientists say.

READ MORE: El Nino: What it is and why it matters

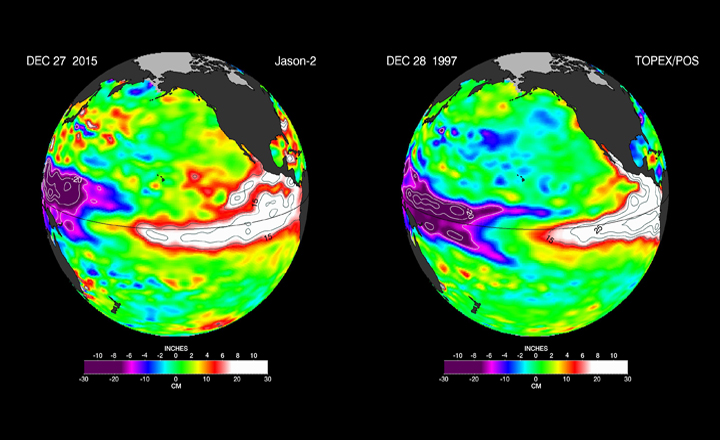

El Niño is characterized by unusually warm temperatures in the equatorial Pacific Ocean and occurs once in about every two to seven years, in varying strengths (conversely, there is also La Niña, which is characterized by unusually cool waters in the same region). The effects of this warming are felt around the world, from heavy rains in California, to warm weather in western and central Canada, to a suppressed monsoon season in India.

In Canada, the effects of El Niño are already apparent: unseasonably warm temperatures have occurred across the country (with not as marked of a departure in eastern Canada, which is typical in an El Niño year): Toronto reached a record 15.4 C on Christmas Eve.

Globally, the phenomenon has reduced rains in Southeast Asia, contributing to massive unprecedented fires in Indonesia; it is also believed to have contributed to heat waves in India and its delayed monsoon rains as well as coral bleaching in the Pacific, droughts in South Africa as well as flooding in South American and a record-breaking hurricane season in the Pacific.

But as much as these effects have been seen, the United States is still waiting.

The much-needed rains for California still haven’t happened.

READ MORE: Ski resorts in southern Ontario feeling pain of El Nino year, some opening summer attractions

“The water story for much of the American West over most of the past decade has been dominated by punishing drought,” said JPL climatologist Bill Patzert. “Reservoir levels have fallen to record or near-record lows, while groundwater tables have dropped dangerously in many areas. Now we’re preparing to see the flip side of nature’s water cycle — the arrival of steady, heavy rains and snowfall.”

Though the rains will bring relief, it will by no means spell an end to the drought.

“Over the long haul, big El Niños are infrequent and supply only seven per cent of California’s water,” Patzert said.

And, though the region is in much need of rain, it’s not always a good thing: as a result of heavy rainfall, landslides and floods are triggered.

El Niño is still expected to remain strong into the winter of 2016, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, with a transition to a neutral phase in late spring or early summer. And that also means that, should we head into a La Niña, we could see opposite effects.

In the meantime, the world watches and waits to see when El Niño– the “little boy” — begins to settle down.

Comments