TORONTO – Days after a great white shark became the first documented of its kind to make a trans-Atlantic journey, researchers tracking her progress were saddened to find that another shark’s signal was being received from Portugal — on land.

Scientists involved in tagging and tracking the female mako shark, named Rizzilient, believe it’s likely that the five-foot shark was caught by a longliner — a boat used in commercial fishing. The sharks are hunted for their fins, a delicacy in some parts of the world.

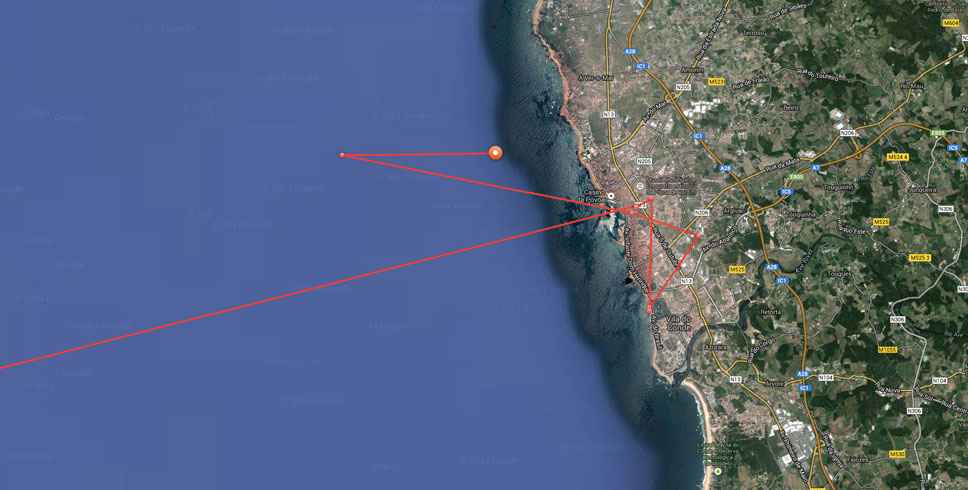

The last few pings — signals sent out by the tracker on Rizzilient’s fin — have come from a town on the coast of Portugal, near Vila do Conde.

“There was a boat that came through there about a week or so ago, that apparently dropped off a lot of sharks,” said Chris Fischer, founder of Ocearch.org, the organization that partners with researchers to tag the sharks. “We’re just trying to understand with a little more depth what happened.”

Often, the sharks are caught, their fins are cut off, and they are thrown back into the ocean to die. It is unknown whether or not this happened to Rizzilient. But it doesn’t look good.

“We know the tag is no longer on her,” Greg Skomal, the project leader for the Massachusetts Shark Research Program told Global News. Skomal tagged Rizzilient in July 2013.

“At this point it’s all assumptions…so one of two things happened: they caught the shark and took the tag off and released the shark. Or they killed the shark.”

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, about 67 species of sharks are listed as critically endangered or endangered. A recent study estimated that about 100 million sharks are caught each year. Mako sharks are not on the list of endangered sharks.

Skomal is disappointed by the loss of Rizzilient, not only as a shark, but as a point of gaining more knowledge about these creatures of the seas.

How do you track sharks? It’s no easy feat.

“In all likelihood, what they were doing was perfectly legal, so they can’t be accused of harvesting a shark that they’re not allowed to harvest,” Skomal said.

“The experiment’s over at this point. It would be great to get the tag back, either to redeploy or to see if it’s got any archived data on it…to learn more,” Skomal said.

Skomal said he’s not sure why Rizzilient wasn’t released.

READ MORE: Australia’s shark cull ‘ill-advised’ way of preventing attacks: expert

The site of the first ping was an old school building under reconstruction. “That’s really odd,” Skomal said. Whoever has the tag is moving around with it. As of March 13, it had moved across the town.

This isn’t the first time the research team has lost a shark due to fishing.

Fischer said that within the last year, they’ve lost one in a fishing village in Mozambique and another off Durman, South Africa in a culling program.

Though there is a fear of sharks, Skomal feels that shark research is shifting the tone.

“People need to want to look after them. People need to want to save them. In order to do that, they must realize that they are the lion of the ocean, the balance-keeper, and appreciate that. And fear typically clouds that.

“But already we’re seeing great awareness,” said Fischer.

Comments