In the last few months, discussion of new coronaviruses has cast a shadow over the hope that the new COVID-19 vaccines will help put an end to the pandemic.

They go by names like B.1.1.7, B.1.351 and P1.

And they seemed to have come out of nowhere. In reality, virus mutation is normal.

READ MORE: COVID-19 variant has overwhelmed Brazil’s healthcare system, expert says

“We’re not surprised by this at all. But I do think that the coverage of them has almost made them seem like it’s a new pandemic where this is actually a natural aspect of viral evolution and viral propagation,” said Dr. Sumon Chakrabarti, who is an infectious disease specialist in Mississauga, Ont.

“It’s normal. It’s not something that’s out of an X-Men movie.”

But near the end of 2020, Kent, in southeast England, became a hotspot for a new variant that had 23 mutations.

It turned out to be the variant now known as the B.1.1.7.

The emergence of a lineage with so many mutations surprised even the most experienced scientists.

“We’d been learning for a year that this virus didn’t change. It was always the same. There were a few mutations here and there,” said Ravindra Gupta, a professor of clinical microbiology at the University of Cambridge.

“We didn’t know that you could find viruses with so many mutations in one virus.“

Gupta is a world-renown virologist who has dual roles. One is in the lab, the other is as a clinician in infectious diseases.

Before the B.1.1.7 variant was discovered, he and his team were studying a COVID-19 patient who had become chronically infected with the virus for more than 100 days.

“In this person, we saw just the most dramatic shift you can imagine,” Gupta told Global News.

READ MORE: Health officials warn Regina is a hot spot for contagious coronavirus variants

A virus’s strategy for survival is to multiply by making copies of itself, but the copies aren’t always identical.

As SARS-CoV-2 replicates, small copying mistakes — known as mutations can happen.

These mutations, when combined with natural selection, allow viruses to quickly adapt and increase the likelihood of being passed on to the next generation, while mutations that make the virus less fit are likely to die out.

Get weekly health news

People with weakened immune systems can have trouble fighting and killing the virus, allowing it to continuously replicate for weeks or months, generating more and more mutations.

In the case of Gupta’s patient, he had cancer. Because his immune system was weakened by chemotherapy, he had a difficult time getting rid of the virus.

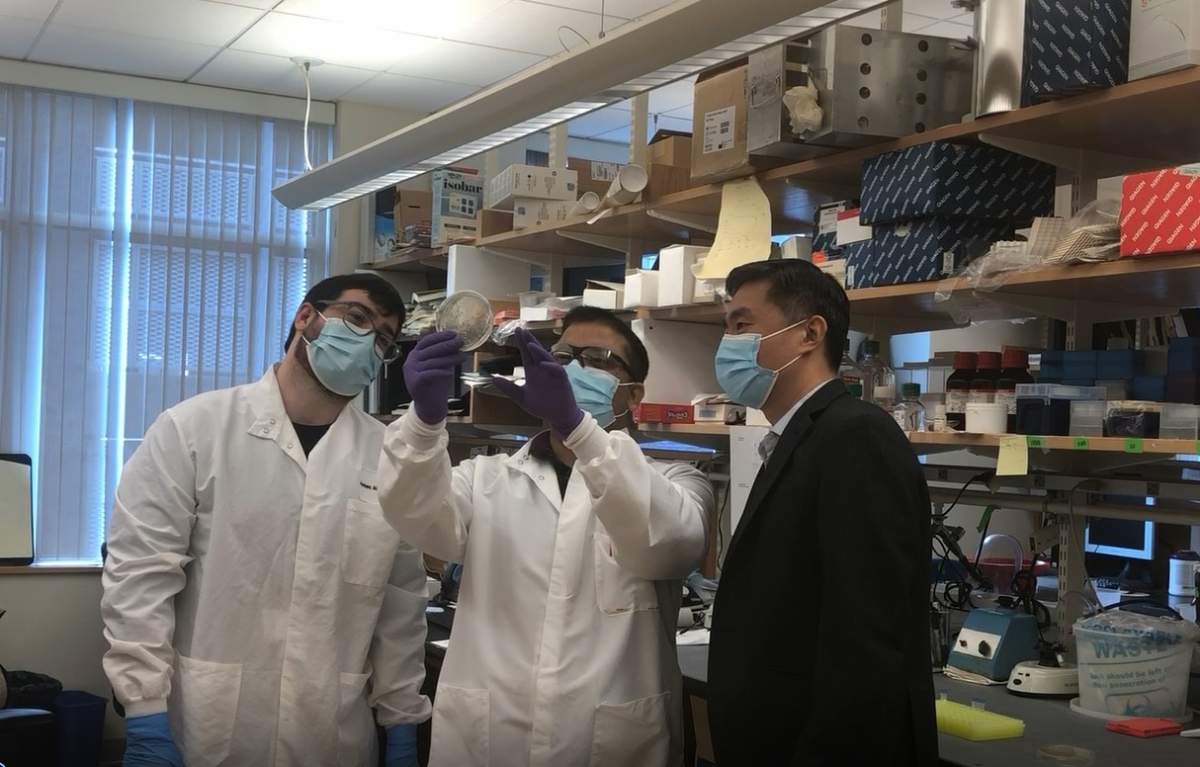

“What we do is we isolate virus from those different samples. And then we sequence them to basically figure out specifically what virus the patient has,” said Steven Kemp, who worked with Gupta, tracking the virus evolution process in that cancer patient.

“And what we noticed was the patient was developing a number of different mutations.”

For example, around day 66, after treating the patient with two doses of convalescent plasma, they saw that the genetic structure of the virus had started shifting.

Convalescent plasma is a type of therapy that uses blood from a person who recovered from an illness. In this case, it was from someone who fought off COVID-19.

“When they’re given to this patient, it seems that a number of mutations arose,” Kemp said, who is a research associate at University College London.

“One of the mutations we found led us to discover the B.1.1.7 variant because this mutation in our patient that had emerged in response to treatment actually was one of the key mutations found in the B.1.1.7,” Gupta said.

“We were the first to actually show that in vitro, these mutations actually had a functional impact. And therefore, this was a sign that the virus was not only evolving, but actually doing things to overcome treatments that we were throwing at the virus.”

Experts believe that the B.1.1.7 variant found in the U.K. may have evolved within a single immunocompromised patient.

“We haven’t been able to identify who the Patient Zero was for the B.1.1.7 strain,” Gupta told Global News. “I know that a number of people have been looking.”

Although chronic infections are rare, a growing number of cases suggest that immunocompromised COVID patients accelerated viral evolution.

In Boston, a 45-year-old COVID-19 patient, who had an underlying autoimmune disease, was ill for 154 days.

During that time, clinicians were trying to figure out whether the patient was being re-infected with new strains of the virus or whether he was potentially so immunosuppressed that he was unable to clear the virus that was in his body.

Dr. Jonathan Li, who is a physician in the division of infectious diseases at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, set out to find the answers.

Over the course of about five months, he took samples from the patient and performed viral sequencing.

Dr. Li said that after he lined up all the sequences, the explanation became clear.

“This patient was not being re-infected with multiple new strains of SARS-CoV-2, but instead his immune system, which was immunosuppressed, was unable to clear this one strain of a virus that was present,” Dr. Li said.

“And in addition, we saw evidence of viral evolution over time where the virus itself was developing new mutations and really in front of our eyes.”

According to Dr. Li, there are a lot of similarities between the mutations found in his patient and the new variants circling the globe.

Unfortunately, both patients in the U.K. and Boston passed away.

But they did provide key insight into the need to control community spread, to protect those most vulnerable and to ramp up vaccinations.

So far, there’s not a lot of information about the risk of the COVID-19 vaccine to immunocompromised people. They were not included in the trials.

It’s currently not even known whether they will be able to have an immune response if they did get the shot.

“I think if you have an immune compromising condition, you are exactly the population we want to get vaccinated and I encourage you to do so,” said Dr. Chakrabarti, who is a physician at Trillium Health Partners.

“The really important thing, if you look at a place like Israel, is that we’re seeing real-world evidence. The vaccine is very effective. And this is a population, including young people, older people — as well as people with impaired immune systems.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.