From ever-changing COVID-19 guidelines and new research to misinformation and conspiracy theories, it has not been easy keeping up with the coronavirus infodemic.

As most of us attempt to navigate through the scientific jargon and make sense of what a variant is, how mRNA vaccines work, or which mask to wear, getting the right word out is important.

In Canada, the main languages used for all official communications are English and French.

While provinces have made their announcements and public health guidelines available in various languages to cater to those populations that don’t speak English or French, some feel governments could have done more to get that messaging out sooner to racialized communities, which are bearing the brunt of the pandemic.

“Communication with the so-called ethnic groups has to be a proactive process — it can’t be reactive,” said Balpreet Singh, legal counsel and spokesperson for the World Sikh Organization of Canada.

A Statistics Canada report published in October 2020 found that in Quebec, Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia, there was additional burden from the COVID-19 disease in neighbourhoods with higher proportions of population groups designated as visible minorities.

The same report also showed that there were noticeable differences in the age-standardized mortality rates depending on the proportion of the neighbourhood population who were South Asian in Toronto.

South Asians make up Canada’s largest visible minority group. There are more than 600,000 Sikhs in the country, according to the WSO, with at least 250,000 in Ontario alone.

“I think the outreach to our community was not where it needed to be for quite some time,” Singh said.

With COVID-19 resources not available in Punjabi in the early days of the pandemic, Singh said the WSO helped translate, contextualize and disseminate public health guidance, reaching out to gurdwaras (places of worship) and international students.

In Nov. 2020, nine months into the pandemic, the South Asian COVID Task Force, a group of medical experts and advocates, was formed to assist South Asian communities across the country.

Such community initiatives have helped raise awareness about things like mask wearing and quarantine, Singh said.

“It’s been largely our own community sort of gathering together and providing that information to ourselves,” he said.

A University of British Columbia medical student took matters in his own hands when he kickstarted the COVID-19 Sikh Gurdwara Initiative at a Surrey temple last November.

With the help of a grant from the Clinton Foundation and the Canada Service Corps, Sukhmeet Singh Sachal and about 100 youth volunteers were involved in the outreach protect that aimed to deliver the government’s message in a culturally sensitive way.

“When we started educating them like, you have to stay six feet apart, that’s the same (length) as your turban, then they started understanding it,” Sachal told Global News in a previous interview.

Get weekly health news

DIVERSEcity, a B.C-based settlement agency for newcomers, launched a social media campaign last April, sharing video messages about COVID-19 in six different languages, including Mandarin, Arabic, Punjabi, Hindi, Korean and Swahili on their social media pages.

Maureen Chang, an immigrant herself from Taiwan and a settlement and support worker at DIVERSEcity, said last year was difficult not just for the newcomers but for all foreign language speakers.

“We were so concerned about a second wave, so before the holiday season, we wanted to highlight again and remind newcomers (of) those public health measures,” she told Global News.

What are the provinces doing?

Provincial health authorities in both Quebec and Manitoba have made health instructions and COVID-19 resources available in 14 different languages on their websites.

“Given the health context, it is very important for the government that ethnocultural communities that have difficulty understanding the French or English language be reached and made aware,” said Marie-Helene Emond, spokesperson for Quebec’s Ministry of Health and Social Services (MSSS).

The leaflet to assist with informed consent to immunization that people receive when they get vaccinated will be translated into 21 languages, she told Global News.

In December, Ontario launched High Priority Communities Strategy to contain the virus in high-risk communities. Under this $12.5-million initiative, the province is developing targeted and culturally appropriate communications to combat misinformation and myths.

“Evidence shows that racially diverse, newcomer and low-income communities have been impacted more significantly by COVID-19 than others, and they need specific supports as they are facing complex barriers to accessing services and enacting core prevention measures,” said Anna Miller, a spokesperson for Ontario’s Ministry of Health.

The Saskatchewan Health Authority has had public health measure posters translated in three other languages, Mandarin, Tagalog and Urdu, besides English and French, and shared with Regina and Saskatoon Open Door Societies.

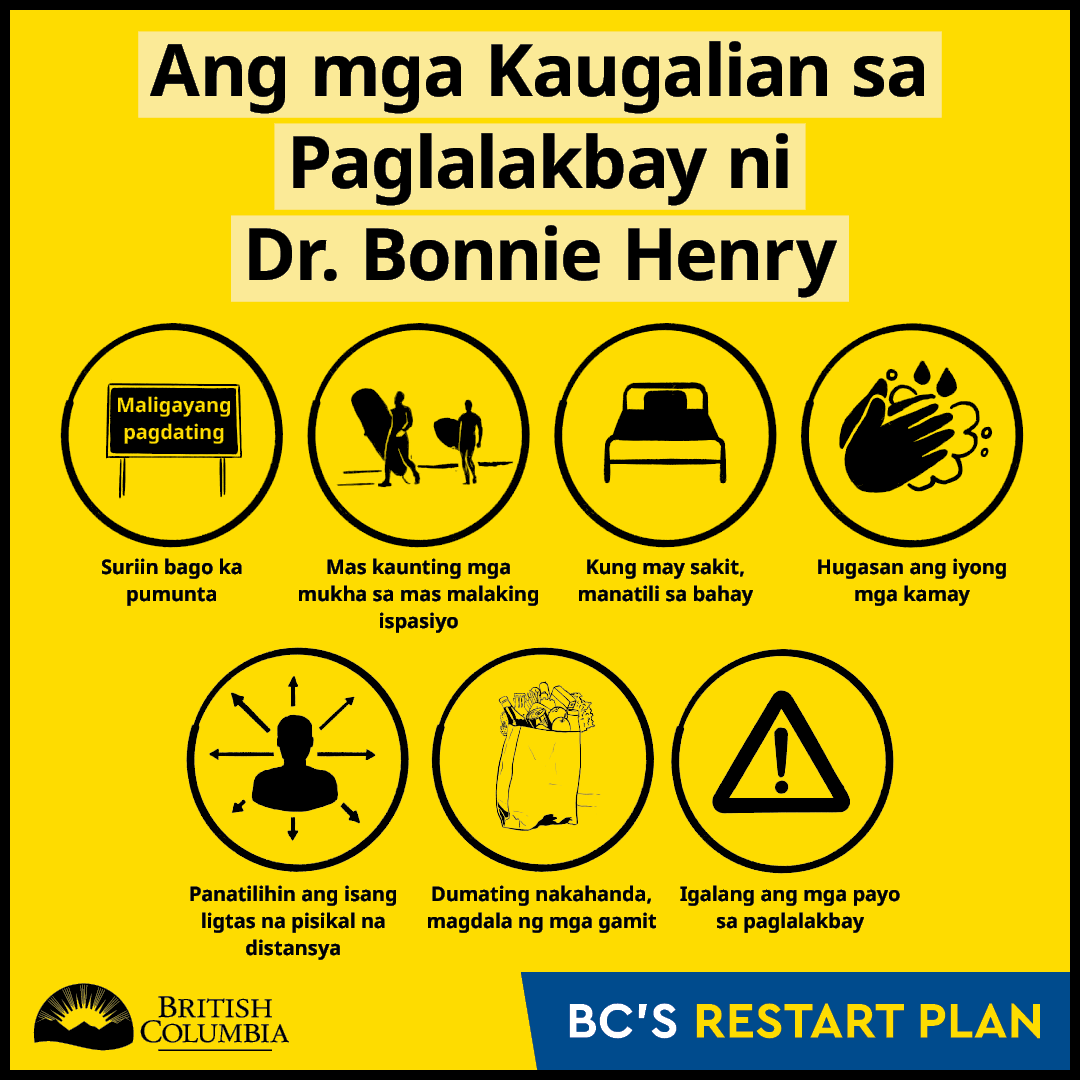

Meanwhile, on British Columbia’s government website, daily COVID-19 statements and other public health content is available in traditional and simplified Chinese, French, Punjabi, Farsi, Tagalog, Korean, Spanish and Arabic.

Glenn Mauring, a Filipino immigrant and an immigration consultant based in Golden, B.C., says this has proven useful for his foreign clientele.

“I think information dissemination is made more effective when announcements are available in various languages.”

Cultural stigmatization

Over the course of the pandemic, Canada has seen heightened cultural stigmatization and a spike in overt acts of racism, especially against people from China, where the novel coronavirus emerged in December 2019, and other Asian communities.

A June 2020 survey by the Angus Reid Institute found that half of the Canadians of Chinese ethnicity indicated being called names or insults as a direct consequence of the outbreak, while 43 per cent said they have faced threats or intimidation.

Another survey by Statistics Canada in July 2020, also showed that Canadians with Asian backgrounds were far more likely to perceive an “increase in harassment or attacks on the basis of race, ethnicity, or skin colour” since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Singh said higher COVID-19 rates in Brampton, Ont., which has a large South Asian population, was being painted as a result of non-adherence to public health guidelines.

“It was very alarming that people were blaming the community as just not caring, and that wasn’t the case.”

Most in the South Asian community are essential workers and front-line healthcare workers, which makes them more vulnerable to getting COVID-19, said Shaizinder Kaur, WSO director of the Saskatchewan chapter.

According to Statistics Canada, 34 per cent of immigrants and visible minorities have jobs with greater exposure to COVID-19 compared with other sectors.

Moving forward as more vaccines become available, Singh said it would be important to communicate the information about the inoculation plan to the elderly in a timely fashion, preferably in their first language.

“The more engagement there is between public health and the communities, the better outcomes you will have,” he said.

Comments