At this point, most of us know the drill when it comes to COVID-19: proper hand hygiene, mask wearing and social distancing.

But does setting fire to cell towers make your list? Probably not. A conspiracy theory linking 5G mobile technology to the COVID-19 outbreak has ignited fears worldwide, prompting just this response from a few individuals in Québec, who set ablaze seven mobile towers.

READ MORE: Trump duped by fake news story of Twitter going down to protect Biden

Although such destructive responses are rare, thousands of digital consumers have absorbed aspects of this falsehood, pushing fringe beliefs into the mainstream despite refutations from the World Health Organization and multiple agencies in Canada and the United States. What started as a conspiracy turned into a real crisis for the people who immediately believed what they’d heard.

My research focuses on critical media studies and ideological representations in news and popular culture. I regularly offer workshops to schools and community groups that engage the public in contemporary media literacy issues. My book, Won’t Get Fooled Again: A Graphic Guide To Fake News, helps readers identify the underlying purpose of the messages they receive and learn how to do basic research before accepting the validity of what’s being presented to them.

Dealing with fake news

Fake news is an increasingly pressing problem. In fact, a 2019 poll found 90 per cent of Canadians reported falling for false information online.

As consumers, we need to learn how to filter content and become our own educators, editors and fact-checkers to ensure the information we act upon is trustworthy. In a constantly changing informational and political environment, it’s no wonder we often struggle to separate fact from fiction.

Research indicates people create misinformation for two primary reasons: money and ideology.

Articles, videos and other forms of content can generate large amounts of money for the websites that host these pieces. Most of their income comes from clicks on advertisements, so the more people who visit their sites, the better chances they have of boosting ad revenue. This feedback loop has led many publishers to lean on false information to drive traffic.

Get daily National news

The threshold for making believable fake news has fallen as well. A conspiracy theorist, for example, can create a web page using a professional template with high-quality photos in just a few clicks. Once the content has been added, sharing it on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and other platforms requires even less effort.

These misinformation and fake-news campaigns amplify and circulate through false digital accounts using automated programs known as bots that use certain keywords to influence and impact conversations among like-minded clusters of people. The results can foment discord on hot-button Canadian policy issues — like immigration and refugees — possibly disrupting election outcomes.

(Alan Spinney), Author provided

Generating anxiety and undermining truth

Canadians are expressing anxiety about the social impact of fake news, with 70 per cent fearing it could affect the outcome of a federal election. The Pew Research Center warns that fake news may even influence the core functions of the democratic system and contribute to “truth decay.”

Dubious and inflammatory content can undermine the quality of public debate, promote misconceptions, foster greater hostility toward political opponents and corrode trust in government and journalism.

The effects of misinformation have been evident throughout the COVID-19 epidemic, with many citizens confused as to whether a mask will decrease the chances of spreading the infection. Similar tactics are being levelled against Black Lives Matter protesters, such as labelling them all as rioters when videos and photos show most behaving peacefully.

Conspiracy theories about the “Chinese virus,” amplified by politicians in Canada and the U.S., have fanned the flames of anti-Asian sentiments following the spread of COVID-19. Data from law enforcement and Chinese-Canadian groups has shown an increase in anti-Asian hate incidents in Canada since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

READ MORE: How to teach kids to hunt out fake news? With dinosaurs, of course

Who and how to trust

Aside from a few social media platforms that identify misleading content and provide a brief explanation, most information online or in print can appear factual. So how can we figure out which sources to trust?

As a sociologist who focuses on critical media studies, I formed focus groups and collected input from my students to create a resources to guide readers through identifying fake news. While regulation and legislation are part of the solution, experts agree we must take swift action to teach students how to seek verification before acting on fake news.

In my findings, students identified several reasons why media outlets post or re-publish fake news, including making mistakes, being short-staffed, not fact-checking and actively seeking greater viewership by posting fake news.

The students pointed to holistic media literacy and critical thinking training as the best responses. This finding runs counter to the tactics currently used by publishers and tech companies to label or “fact-check” disputed news.

One student summarized this mindset best: “As citizens and consumers, we have a responsibility to be critical. Don’t accept stories blindly. Hold those in power responsible for their actions!”

Getting multiple perspectives is a great way to expand our digest of viewpoints. Once we can see a story from more than one angle, separating truth from falsehood becomes much simpler.

At this point, I transitioned from recording perceptions of fake news to determining how to identify it. Providing students with information about the nature and agendas of fake news, in an immersive format, seemed to be a key step in engaging and cultivating their critical literacy capabilities. Information delivery was a key consideration.

(Alan Spinney), Author provided

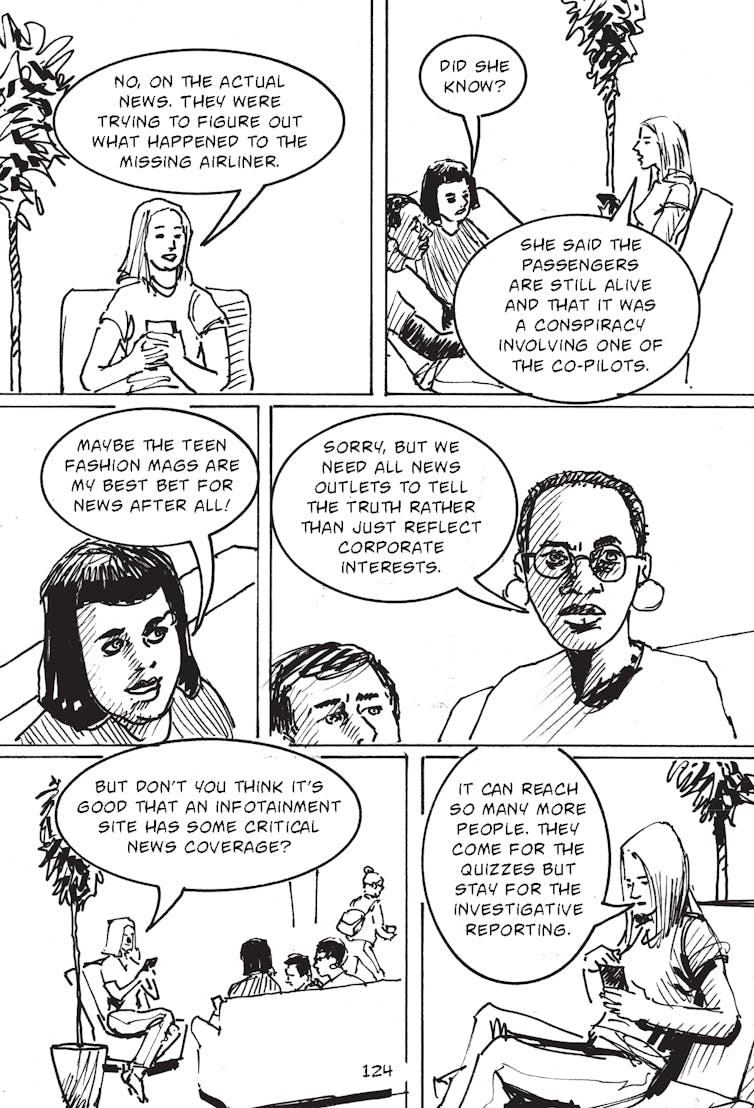

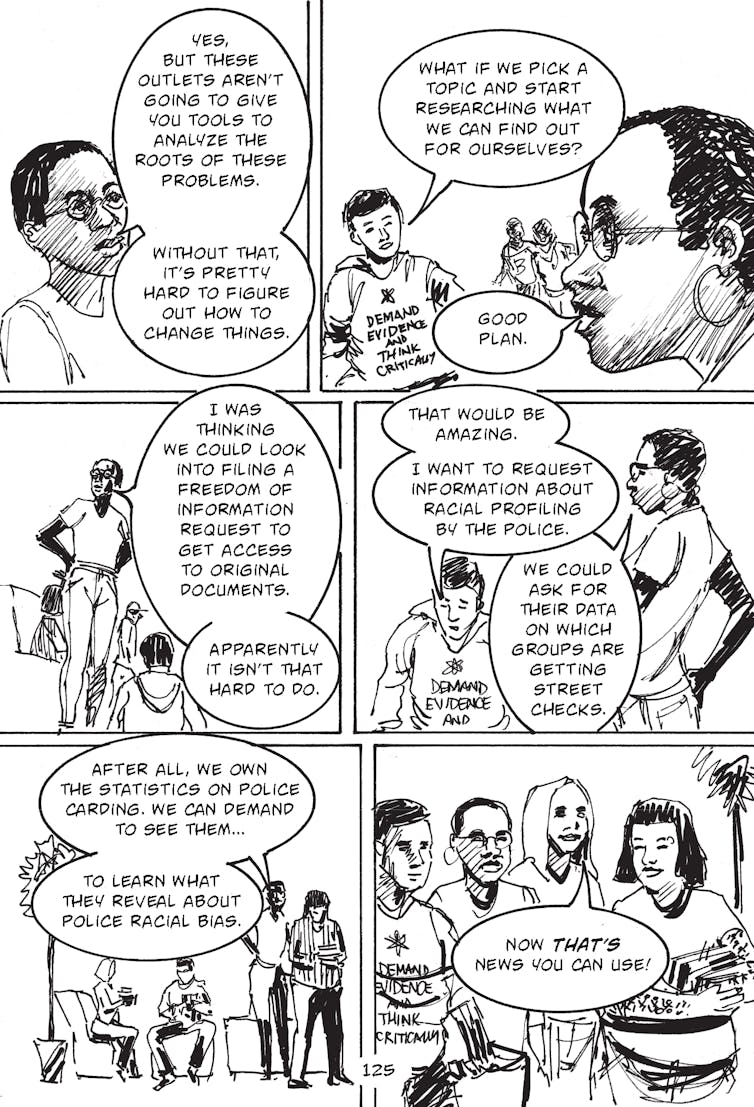

Illustrating the narratives

Researchers have shown graphic narratives can accelerate cognition by focusing the reader’s attention on crucial information. Images clarify complex content, especially for visual learners. Comic books require readers to create meaning using multiple factors that helps develop a complex, multi-modal literacy.

A major goal of my book involves unpacking the motivations behind the news we consume. Consider why a particular person was interviewed: Who do they represent? What do they want us to believe? Is another point of view missing?

Won’t Get Fooled Again: A Graphic Guide to Fake News is the culmination of my research and the insights drawn from media literacy scholarship. This guide helps readers understand what fake news is, where it comes from, and how to check its accuracy.

If there’s one habit my students and I hope everyone will develop, it’s this: pause before sharing news on social media. Double-check anything that immediately sparks anger or frustration and, remember, fake news creators want a reaction, not thoughtful reflection.Erin Steuter, professor of sociology, Mount Allison University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

Comments