Two Ontario researchers say they are challenging an “accepted truth” about the novel coronavirus believing that the “door” used to enter and infect a cell may not be the entry point widely accepted by many in the medical community.

“Our finding is somewhat controversial, as it suggests that there must be other ways, other receptors for the virus, that regulate its infection of the lungs,” said Jeremy Hirota, co-lead scientist from the Research Institute at St. Joseph’s hospital and assistant professor of medicine at McMaster University.

Hirota told Global News the research is essentially a study on the entry points of viruses in the human body. In simpler terms, Hirota says every virus needs to find “the door to the house” to get into a cell.

“If we figure out what those doors are, maybe we can barricade them, maybe we can lock them,” Hirota said.

At present, world scientists believe the entry of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) into cells occurs through a receptor on the cell surface, known as Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which is present in the cells of most organs including tissue of the lung type II alveolar cells.

Get daily National news

But co-lead Andrew Doxey, professor of biology at the University of Waterloo, says their research points to very low levels of ACE2 in human lung tissue.

“Finding such low levels of ACE2 in lung tissue has important implications for how we think about this virus,” Doxey said. “ACE2 is not the full story and maybe more relevant in other tissues such as the vascular system.”

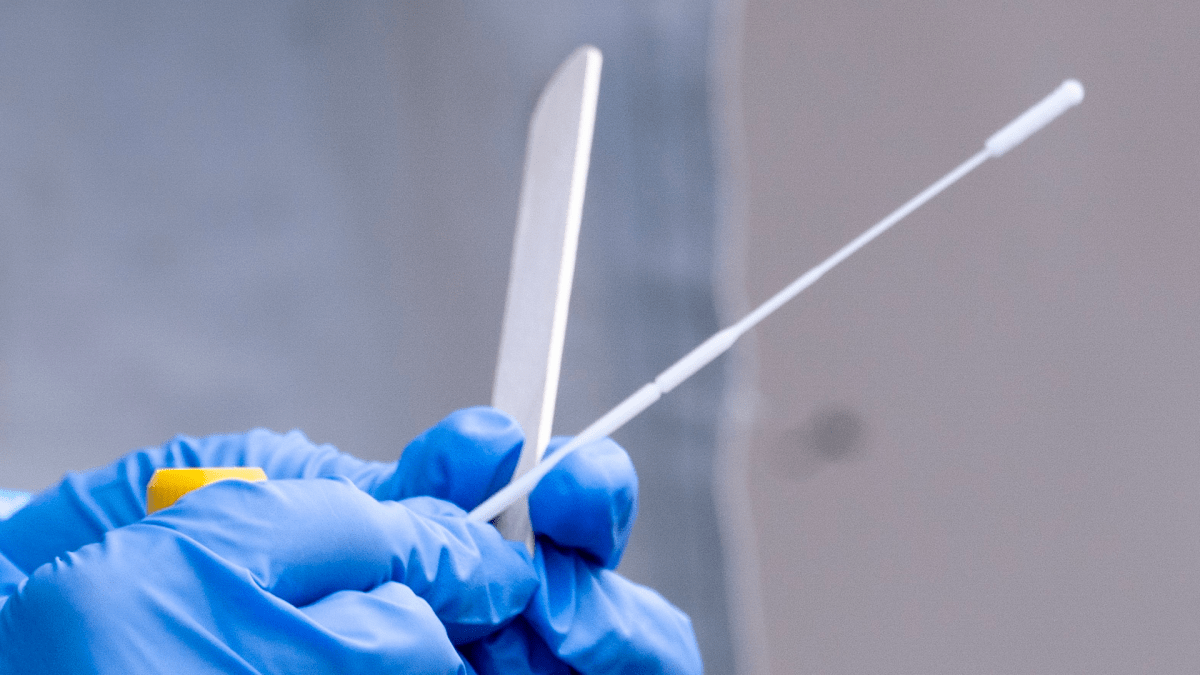

The McMaster-Waterloo team have turned their study to using nasal swabs, collected for clinical diagnoses of COVID-19, to explore alternate additional infection pathways and different patient responses to infection.

The team believes the samples will provide some genetic information on the development of the disease in a patient with the hope of better identifying the infection and treating patients at risk of developing serious complications.

“We think it is the lung immune system that differs between COVID-19 patients, and by understanding which patients’ lung immune systems are helpful and which are harmful, we may be able to help physicians proactively manage the most at risk-patients,” Hirota said.

The researchers say the study may ultimately lead to predictive algorithms tied to morbidity and mortality which could predict and optimize health care delivery for those most susceptible to the virus.

The research has received support in the form of three grants, including one from the Ontario COVID-19 rapid research fund. The team’s findings have generated interest in the medical community after a paper on the findings was published in the European Respiratory Journal.

Hirota says the hope is to have useful data determining which individuals may be at greater risk to COVID-19 than others within six to 12 months.

“We’re looking for additional partners to collaborate with us in moving this research forward, as we believe there is an opportunity to develop diagnostic devices with this information,” Hirota said.

- Carney unveils ‘Buy Canadian’ defence plan, says security can’t be a ‘hostage’

- Rhode Island shooter killed ex-wife, son before bystanders intervened: police

- Canadian immigration officers investigating hundreds identified by extortion task force

- ‘Canada can broker a bridge,’ Carney says on new trading bloc efforts

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.