The death of George Floyd has triggered a waterfall of questions about the use of force by law enforcement — the method of restraint used on Floyd being one of them.

Floyd, a Black man, was held down by a white police officer who kneeled into his neck. Harrowing video shot by a bystander shows Floyd handcuffed, lying on the cement facedown as he pleads he can’t breathe.

An autopsy conducted by Floyd’s family found he died of suffocation. An official autopsy listed in the criminal complaint against the officer filmed kneeling on his neck ruled out asphyxiation. Summary findings released by the Hennepin County Medical Examiner’s Office on Monday said Floyd had a heart attack while being restrained by officers.

The technique used by the officer to restrain Floyd has garnered widespread condemnation from police officials and experts.

In Minneapolis, where the incident took place, police are allowed to restrain suspects’ necks if they’re deemed aggressive or resisting arrest. A number of other major metropolitan police departments have banned the method since Floyd’s death. The rules and procedures for restraints also vary internationally.

In Canada, it’s a technique that’s strongly discouraged, said Rob Gordon, a criminologist at Simon Fraser University.

“Anything that involves restrictions on respiration of an arrested person is basically not acceptable,” he said.

Police officers can use force during an arrest, he said, but the degree of that force needs to follow three fundamental principles: proportionality, necessity and reasonableness. Those principles were made clear in the Supreme Court decision of R. v. Nasogaluak in 2010, in which an intoxicated driver was punched repeatedly while resisting arrest, ultimately breaking his rib and puncturing a lung.

According to Gordon, the Floyd case “fails” all of them.

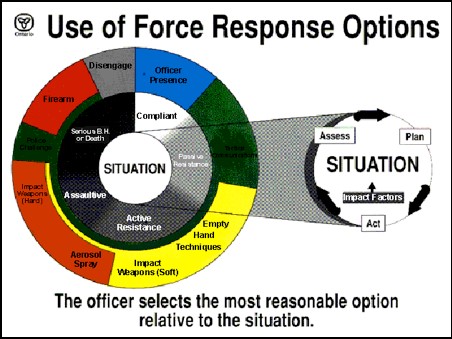

There is some variation across Canadian police forces regarding use-of-force practices, but most follow a “progressive use of force continuum model,” according to Greg Brown, a 35-year police veteran in Ontario who now researches policing at Carleton University.

“You could technically lean on somebody’s neck if you wanted to, but you would have to justify that behaviour after the fact. In a situation where an individual is handcuffed and immobilized and there are four police officers there, that’s a very difficult argument to sustain.”

The RCMP does not “teach or endorse any technique where officers place a knee on the head or neck” in any of its academy or divisional training programs, a spokesperson told Global News.

“Incidents involving police use of force are complex, dynamic and constantly evolving, oftentimes in a highly charged atmosphere. Police officers must make split-second decisions when it comes to responding with intervention options, if necessary.”

In the video, Floyd, while on the ground, has his head turned to the side and does not appear to be resisting. As the officer continues to hold him down, Floyd complains about not being able to breathe before he eventually falls silent and becomes motionless.

Brown said that based on the video, it’s clear he’s not resisting.

“It’s pretty obvious to anybody watching that the officer’s behaviour was atrocious and that there can’t be any justification for that,” he said.

Derek Chauvin was originally charged with third-degree murder, but the charge was upped to second-degree murder on Wednesday. The three other Minneapolis officers at the scene have been charged with aiding and abetting a murder.

Protocol for Canadian police

Get daily National news

Officers in Canada are required to follow the tiered protocol, which designates what type of resistance requires what sort of response.

The first is passive resistance, which Brown said would be a verbal non-compliance.

“Protesters who aren’t kicking or punching, they’re sitting on the pavement, that’s passive resistance. ‘I’m not complying with what you’re telling me to do, but I’m not going to physically resist,'” he said.

The second layer is “more active,” he said, where someone might “pull away from” an officer’s grip. The model increases from there to an assaultive level, which might require “defensive tactics,” and a more serious assaultive level, which could require deadly force.

But no situation is rigid, he said, and officers are supposed to revert to other layers as the arrest unfolds.

“Officers are continuously reassessing what the threat is. Use of force is not supposed to be a binary choice, it’s supposed to be fluid. It can go up, and then it can come down,” he said.

Should an officer place handcuffs on a person, the use of force “has to drop dramatically,” Brown said because the initial possible threat has “significantly diminished.” It’s hard for an officer to justify any continued use of force after that, he added.

The protocol is similar to one imposed in U.S. police training, according to Brown, it just wasn’t followed in this case. Nor is it the first time it hasn’t been.

Brown and other experts agree that improvements can be made to police training.

Brown said that in Ontario, officers are “lucky” if they get more than 12 hours of training on the use of force in a single year. He believes officers aren’t exposed enough to real-life situations prior to being sent to the streets. And while there’s separate training on bias, he said it’s not necessarily linked to use of force during programs.

A greater emphasis in police training around racial bias and prejudice is long overdue, according to Dexter Voisin, dean of the University of Toronto’s Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work.

“Often you get a checkmark. The box is checked, and that’s it. But this has to be ongoing because you’re trying to change a culture around the perception of communities of colour,” he said.

Floyd’s death has put renewed emphasis on excessive use of force by police officers, particularly with Black citizens. The cases of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and Dominique Clayton have again been brought to the forefront.

“We’re all impacted by race, we all internalize, we all project it. Ongoing training in a systematic way is one way to get us there,” Voisin said.

Incidents in Canada

Canada is far from immune from instances of excessive use of force by police, including those involving racialized citizens. In fact, many cities have had their own long history of deaths, incidents and investigations involving police that have reignited anti-Black racism concerns.

Andrew Loku is a critical example. Loku was shot and killed while he held a hammer in his hands at a Toronto apartment complex in 2015. The jury at a coroner’s inquest found the death to be a homicide, but inquests do not determine criminal or civil liability. Ontario’s police watchdog, the Special Investigations Unit, took over the case and did not lay any charges against the officers involved.

Sammy Yatim is another. The 18-year-old was shot and then Tasered by Toronto police as he stood aboard an empty streetcar brandishing a knife in 2013. His death sparked citywide protests and a lawsuit against the officer involved. The officer in the case, James Forcillo, was convicted in 2016 of attempted murder and spent time in prison for that and another charge related to breaching bail conditions.

Years prior, in 2007, the death of Robert Dziekanski stirred rage over police use of force. Dziekanski was Tasered by four RCMP officers at the Vancouver International Airport after spending approximately eight hours in customs.

In just the last few days, three incidents involving police in Canada have further emphasized concerns. In Toronto, the falling death of Regis Korchinski-Paquet in the presence of police officers has sparked outrage and protests as the province’s police watchdog conducts an investigation.

In Nunavut, RCMP are investigating a video that appears to show a police officer ramming a vehicle into a man during an arrest. Police allege the man was intoxicated and fighting with other people.

In Kelowna, B.C., RCMP are conducting an internal review after a video surfaced showing a police officer punching a man during an arrest.

Part of the issue surrounding the disproportionate use of force by police against racialized Canadians lies in policies, explained Voisin.

“If policies are still guided by implicit or explicit bias, it’s going to have similar outcomes,” he said. “If you remove chokeholds, that doesn’t prevent Black folks from being shot, being perceived as being dangerous.

“You can revamp all the policies, but if you don’t address the underlying issues, they’re still going to be applied differentially.”

Voisin said the Floyd case and its fallout are an opportunity for police and community leaders to take a hard look at policies and have “more proactive dialogues” to circumvent future incidents.

Law in Canada

Inquests have followed some of Canada’s high-profile cases. Despite this, experts believe that police in Canada are not following through on recommendations aimed at dealing with such situations.

To further complicate things, the legal constraints on a police officer’s use of force are deeply rooted are enshrined in the Criminal Code, which is a “main problem” for cases in Canada, said Ron Stansfield, a sociology professor with the University of Guelph and former Peel Regional Police officer.

Under Section 25(1) of the Criminal Code, the use of force to make a lawful arrest is justified if the officer believes on “reasonable and probable grounds” that it is necessary — and if only as much force as necessary is used. It goes on to say that use of force that is intended to or causes death or serious bodily harm is prohibited unless the police officer has a reasonable belief that the amount used is necessary to protect themselves or another person.

“As a result of this section, it’s rare that a police officer is convicted of culpable (i.e. blameworthy) homicide,” he said. “If the police officer testifies they feared for their life at the time they used lethal force, in the absence of other compelling evidence, they will be acquitted.”

But some of this rests on how the law is interpreted once — or if — charges are brought forward, said Jihyun Kwon, a PhD candidate in criminology at the University of Toronto who is researching accountability and oversight of law enforcement agencies.

“The law we have right now actually may not be a bad one in and of itself, but it’s the way it’s interpreted. It’s up to interpretation of whoever is making the decision — judges, oversight bodies — there are many ways officers are overseen … but all of that has failed consistently,” said Kwon.

In many ways, it comes back to training. Kwon said an officer’s response to certain situations tells us “about the culture and approaches of day-to-day policing.”

“It’s about how the officers are trained and socialized into thinking about the suspect about the suspect they’re dealing with or even the general public.”

— With files from the Associated Press

Comments

Comments closed.

Due to the sensitive and/or legal subject matter of some of the content on globalnews.ca, we reserve the ability to disable comments from time to time.

Please see our Commenting Policy for more.