With the meth task force expected to report to the provincial government in June, street-level addictions advocates in Winnipeg say the task force has yet to contact them about their experiences or ideas.

Dane Borget is a former meth addict and founder of Jib Stop, a peer-to-peer phone line to help other addicts. He said his program is now being run out of St. Boniface Street Links, and neither he nor his program partners have been contacted about their experiences.

“They haven’t asked … what’s working, what isn’t working, what they can do differently. So they aren’t talking to all the people that are involved with this,” said Borget.

“They have people in from bureaucrats, from high levels of government involved, and I think they need to be talking more to the non-profit sector, the people who are actually dealing with these people on a regular basis.”

The task force, called the Illicit Drug Task Force, was put together by the provincial government at the end of 2018 with a mandate to report on the best way to move forward dealing with the meth crisis.

The task force consists of 14 people, from the WFPS, the WRHA, police services, Manitoba Justice, Health Canada and two non-profit directors, including Rick Lees of the Main Street Project and Kelly Holmes of Resource Assistance for Youth.

Mayor Brian Bowman told Global News earlier this week he expects the report from the province to filter down to the city by the end of June.

Earlier this year, the province opened a number of Rapid Access Clinics, designed to try to quickly connect addicts with resources in the community, no appointment needed.

WATCH: Violent weekend means not enough cops to deal with meth crisis: Winnipeg police union president

Dr. Ginette Poulin told 680 CJOB that the clinics are catching on.

“We’ve been about eight months in and what we’re seeing is large uptake in terms of Manitobans seeking these seeking these clinics,” said Poulin.

More than 1,000 Manitobans have accessed the clinics for care, and about 600 of them are using the clinic to follow up with other services, she added.

Get breaking National news

“So that tells us it’s meeting the need,” she said. “Even if there are wait times elsewhere, people are accessing the counselling services, they’re receiving medications.”

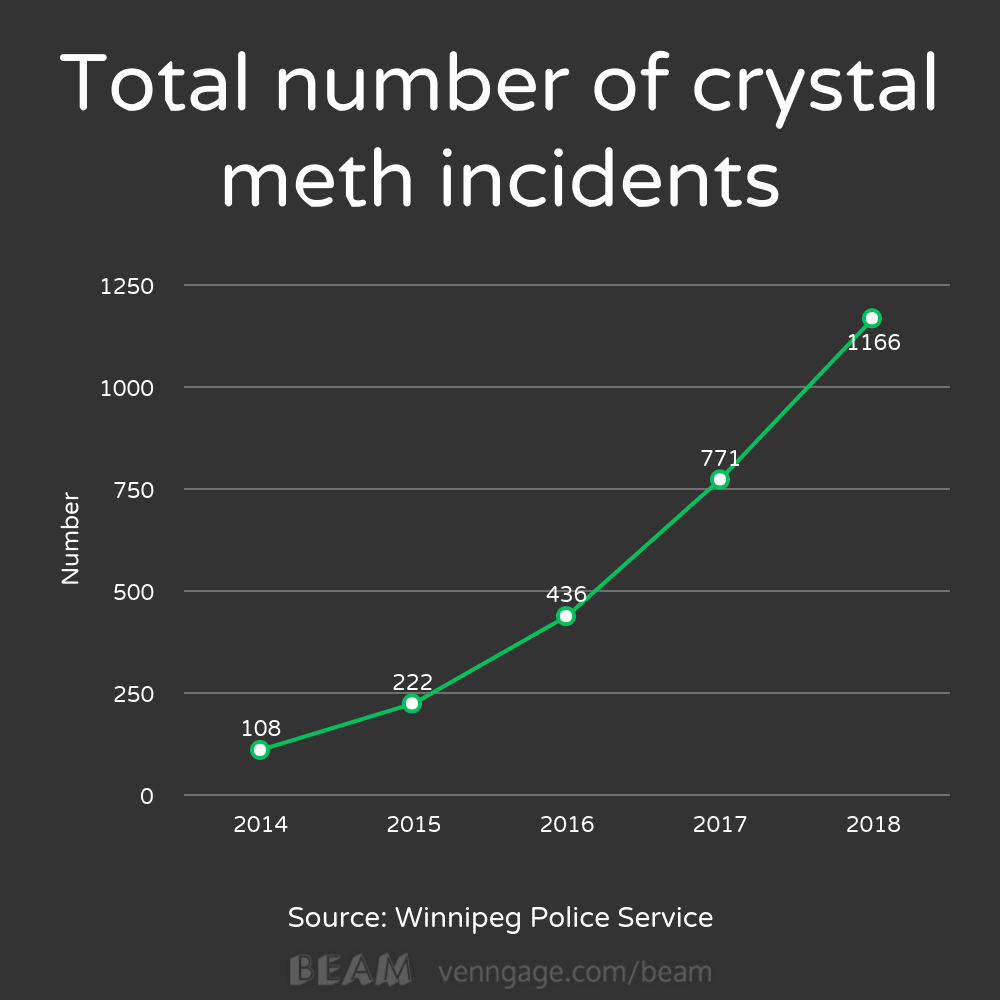

However, while the numbers of people trying to access services is going up, the number of incidents police, health care workers and paramedics have had to deal with are also rising steadily.

By the numbers

While other drug and addiction waves have come through the city, meth is unique in that it can induce a level of violence and paranoia that other addictive substances generally don’t, said Insp. Max Waddell with the WPS.

“I don’t know what it is about meth, but it causes people to see forms of violence, see that they’re constantly being attacked by a machete and things,” he said.

From there, they procure a weapon out of a perceived need for safety, then end up using the weapon to commit property crimes, or theft from motor vehicles, or violent robberies, he added.

The Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service say they have seen meth-related incidents increase 10-fold over five years.

The number of homicides in 2018 that were meth-related came in at six out of 22, and so far this year, at least five of the 18 homicides so far are also meth-related. Winnipeg police said that number may rise as investigations into recent homicides continue.

Winnipeg police have said repeatedly that meth-related crimes from property crime, robbery, and theft to car-jackings and assault are all up over the past several years. Bike theft, which is an easy way for meth addicts to make cash, is up “significantly.”

On Tuesday, police warned that the number of zip guns found in the city is increasing, and attributed that to bike theft due to meth.

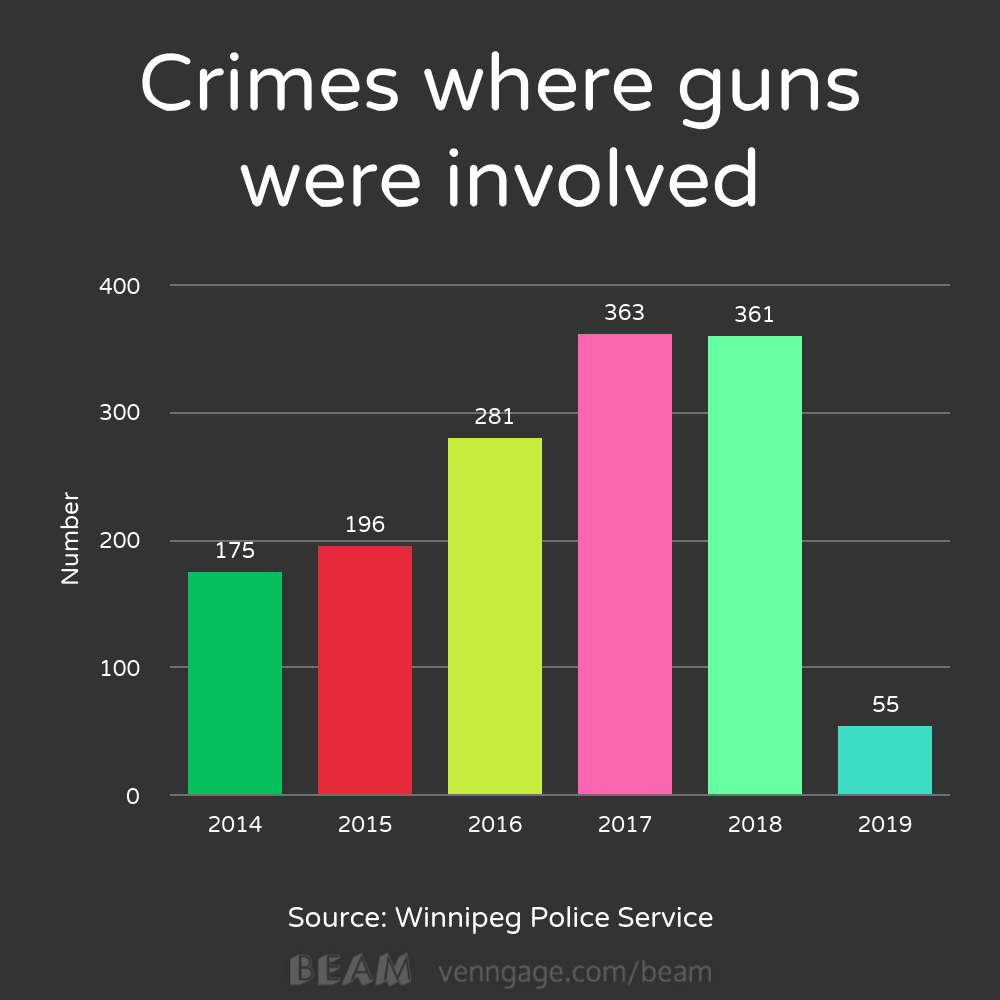

Gun crime overall has been rising significantly in the past several years, said Waddell.

The last three years have seen a particularly high increase, said Waddell, and that coincides with the rise of fentanyl and methamphetamine hitting Winnipeg’s streets.

In 2018, there were 159 people arrested for meth possession. That number is steady so far into 2019.

Over at the WRHA, the nurses union has raised concerns for months about nurses and patients facing an increasing number of violent incidents.

A ‘Code White‘ is called when there is a violent or aggressive incident in the hospital or when a staff member feels they need to call for help.

According to statistics from the Manitoba Nurses Union released in September 2018, the number of patients high on meth admitted to emergency rooms has increased by 1,200 per cent since 2013, which they say has resulted in a dangerous working environment for people in the medical field.

The number of people who are admitted to ERs daily suspected of being under the influence of meth has gone from about one a day in 2014 to about seven a day in 2018, said a spokesperson for the WRHA.

In 2019, that is trending higher at about eight per day so far.

So what do we do?

The recommendations made in the report will not be known for at least another month. But Borget said what he wants to see most is a 24/7 withdrawal management centre, along with a large increase in accessible, timely addictions services.

“When somebody wants to quit, that feeling of willingness is often brief,” said Borget.

“But if somebody has to wait a month or two months to get into treatment then they’re basically going back, straight out to the streets because that’s such a long wait.

“That being said, I’m not sure what another report is going to do.”

WATCH: ‘Illicit drugs draw no borders’: WPS says drugs in all areas of city

Comments

Comments closed.

Due to the sensitive and/or legal subject matter of some of the content on globalnews.ca, we reserve the ability to disable comments from time to time.

Please see our Commenting Policy for more.