The 2017 federal budget, entitled Building a Strong Middle Class, has much less new spending than the last one, and no plan for eliminating the deficit. Here’s a quick glance at the budget’s broad strokes.

New spending

Very little new spending was announced in this budget – just $5.7 billion over the next six years. Contrast that with Budget 2016, which announced $26.5 billion in new funding over 2 years.

Not only that, the government is building in a $3-billion contingency fund into their planning – a cushion in case economic circumstances change.

READ MORE: Federal Budget 2017: How the budget will affect your pocketbook

So why so little new funding?

“One of the reasons that it’s so small is they did a really big announcement last year and they’re still trying to execute on a lot of that spending, particularly infrastructure spending,” said Beata Caranci, TD Economics chief economist. Having two big-spending budgets back-to-back can shake market confidence, she said.

She also thinks that if the government wants to maintain a stable debt-to-GDP ratio, then they just didn’t have much room to spend more.

Get weekly money news

Read more: Federal budget 2017: Trudeau government projects $28.5 billion deficit in 2017-2018

Ian Lee, associate professor at Carleton University’s Sprott School of Business, thinks that the Trudeau government might also be looking south.

“(Trudeau) is keeping his powder dry, to use an old phrase, because he’s got to wait to see what they’re doing in Washington and to see what interventions are needed on our side to respond to what’s going to come out of Washington.”

If the Trump administration implemented a tax on Canadian goods, for example, it could harm the Canadian economy and require government intervention, he said.

“He’s got to maintain the fiscal flexibility right now until they know how much it’s going to cost us to respond to the Trump administration.”

- Attack on Iran triggers global flight disruptions, impacts Canadian travellers

- WWE Hall of Fame ring belonging to wrestling legend recovered after stolen

- Carney calls for protection of civilians as U.S., Israel strike Iran

- Quebec politician praised for speaking openly about menopause symptom in legislature

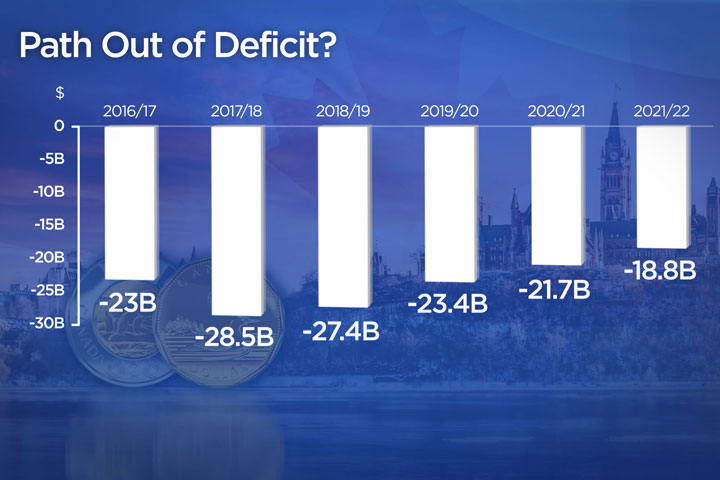

The deficit

The government expects that they will continue to run deficits year by year, with no end in sight. The deficit will hit a high of $28.5 billion in 2017-18.

Economists have two views on deficits, said Caranci. Some aren’t happy to see deficits during relatively good economic times.

“If you can’t ever show a balance over a five to six year period, what does it take to get you there?”

The other view is, are you spending on the right things?

“Are you putting money towards initiatives that could potentially enhance productivity growth or enhance labour force participation?” she asked.

Although it’s hard to prove whether a specific budget initiative enhanced or didn’t enhance growth, to her, modest deficits are acceptable.

READ MORE: Federal budget 2017: Big investment in affordable housing, nothing to cool red-hot markets

“Showing zero versus a couple of billion when you have almost a $2 trillion economy is small,” she said.

Lee said he isn’t worried about the specific total so much as the fact that there is no plan to return to a balanced budget.

READ MORE: Federal budget 2017 is a plan to train, but not retain, Canadian brains

“There is no date and no commitment by the government on when they’re going to return to balance,” he said.

“Deficits are very useful. They have a purpose,” he said. When the economy is good, you try to balance the budget, so that when the economy is bad, you’re better able to ramp up spending to help.

“If we return to recession in a year or two years’ time, what are you going to do at that point because you’ve been printing money and running significant deficits during the good years?”

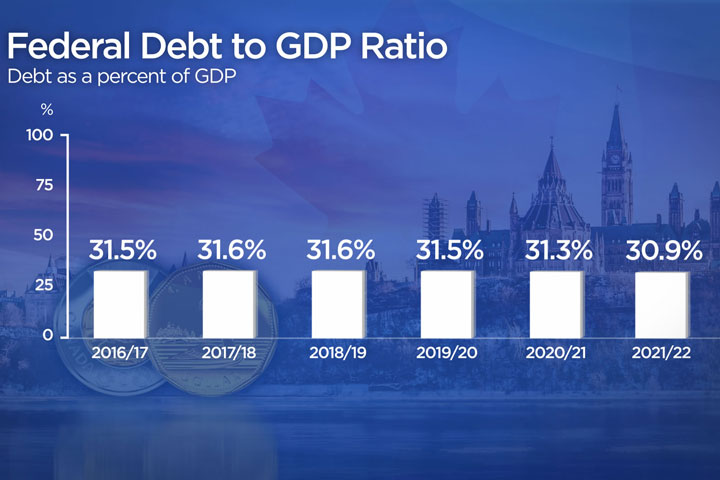

Debt to GDP

The debt to GDP ratio is projected to remain about the same every year – at about 31.6 per cent. It will slowly creep down to 30.9 per cent in 2021-22.

“It’s often used as a measure of how anchored your policies are to the economy. So what are your spending initiatives relative to your income, which is your economy?” said Caranci.

Markets start to worry when the debt-to-GDP ratio creeps up to 40, 50 or 60 per cent, she said, but there isn’t a consensus on an optimum level.

READ MORE: The biggest losers: What’s missing from the 2017 federal budget?

“Canada actually fares fairly well on that, in terms of a debt-to-GDP ratio, compared to our G7 peers.”

This is fine for now, said Lee.

“Right now, there is no crisis. There is no threat to Canada, absolutely.”

But he worries about continued deficits, regardless of how they affect the GDP ratio. “It’s going to reduce our flexibility and degrees of freedom.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.