Look out, Canada: Old people are taking over.

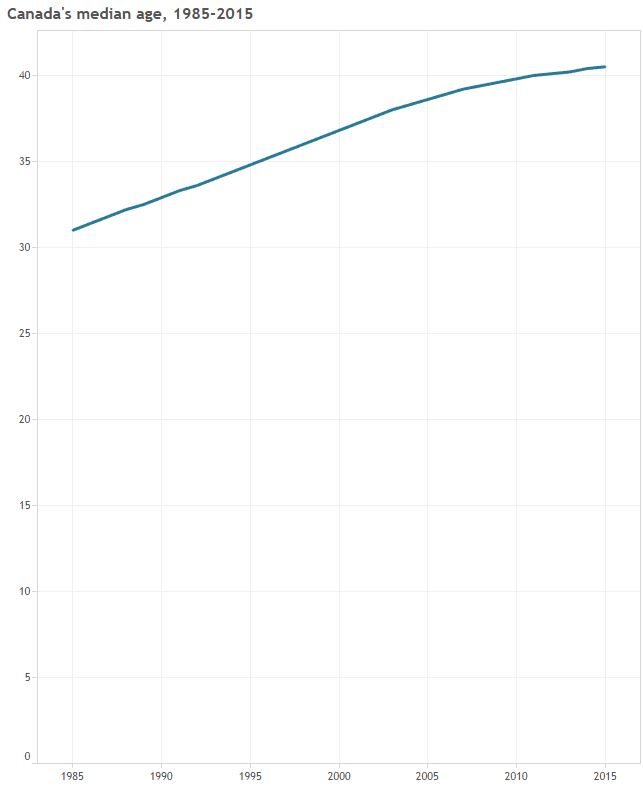

At the same time, Canada’s median age is the oldest it’s ever been – 40.5 years old, up from 38.6 in 2005 and 31 in 1985.

But before you freak out, keep in mind it’s hardly a new trend: Canada’s population has been aging for ages.

“This is exactly what people had seen coming,” says University of Calgary economist Trevor Tombe.

“This is not news to anyone.”

But are we ready for it?

Depends whom you ask. And where you look.

READ MORE: Do governments actually create jobs?

Aging workforce

More older people and fewer younger people means you need to have more of those older people working if you want your workforce to grow — or even keep from shrinking.

If Canada’s next prime minister wants to achieve anywhere near Stephen Harper’s goal of 1.3 million net new jobs by 2020, the rate of its seniors postponing retirement in favour of working will have to grow.

The labour force participation rates of Canadians 55 and over are already growing – from about 23 per cent in the mid-1990s to 37 per cent in 2015.

But Tombe figures they’ll have to keep increasing to sustain economic growth — to about 40 per cent, he thinks.

There are things policy-makers can do to facilitate older people working, but as medical advances mean people stay healthier, longer, it may happen anyway.

“I think it’s going to increase regardless of what governments do,” he said.

“I think it’s a natural trend that we are seeing … and that we will continue to see.”

Immigrant infusion

As Canada’s population growth slows, the country depends more than ever on immigrants to keep its economy healthy and its culture vibrant.

But Canada’s influx of immigrants last year, about 239,000, was the lowest it’s been since 2006-07.

“I think that number could stand to increase,” Tombe said. He figures about one per cent of Canada’s population — 350,000 people, or 110,000 more than we’re bringing in now — could be absorbed as new immigrants annually.

“Immigrants tend to be much younger, they’ll work for many years, so that’s absolutely something that should be on the table.”

That goes for refugees as well, Tombe notes: Refugees’ employment earnings catch up to those of other Canadians relatively quickly, he said, and their reliance on social assistance, if any, is short-lived.

READ MORE: Are refugees an economic burden?

“I think all parties recognize the importance of immigrants in terms of Canadian history,” he said.

“The issue, really, is on the bureaucratic side — the time it takes to process an immigration application is ridiculous.”

The need for new Canadians in the workforce also makes it even more crucial that Canada addresses issues such as accreditation that are keeping immigrants unemployed or under-employed — something the Royal Bank of Canada estimates costs the Canadian economy billions annually.

Last year, recently landed immigrants were almost twice as likely to be unemployed as their Canadian-born counterparts. University-educated recent immigrants were almost three times more likely to be unemployed than university-educated Canadian-born workers.

Health care under pressure – but not the way you think

As you get older, your body’s resilience diminishes. Older people are more likely to find themselves subject to an array of intersecting health conditions, and while we’ve gotten far better at treating them, it costs the health case system a lot.

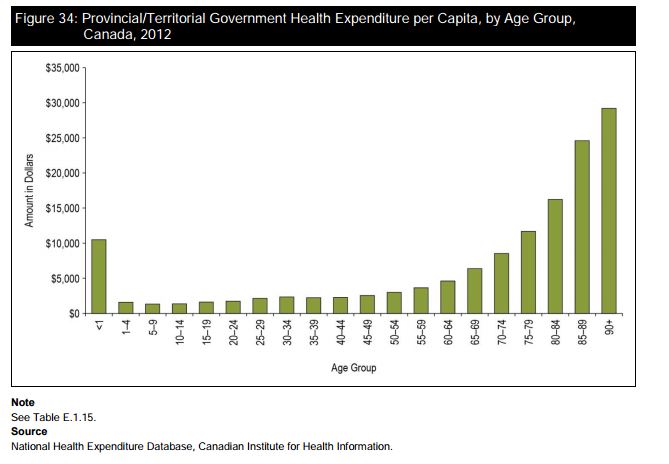

Health spending per capita rises dramatically the older you get:

“While Canadians older than age 65 account for less than 15 per cent of the population, they consume 45 per cent of provincial and territorial government health care dollars,” reads a 2014 Canadian Institute for Health Information report.

But it’s not as catastrophic as it sounds: Population aging is only responsible for about a sixth of annual hospital cost increases, that report found.

“The older population is growing but the very good news is the older population is in much better health than it used to be,” says Michel Grignon, director of McMaster University’s Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis.

“An aging population may not cost much more, but obviously it has different needs. I don’t see much action on that front.”

The Canadian Medical Association has called for a national seniors strategy to deal with the growing health needs of Canada’s elderly.

“Our system was created over half a century ago to meet the needs of a much younger population and we have not adapted to meet the growing number of aging Canadians,” their site reads.

Canada’s health care system deals best with acute health crises: You’re very sick or hurt; you get treatment; you get better; you go home.

But more old people means more chronic, overlapping conditions that can last for years.

“We still have a healthcare system that works well for acute episodes. We’re not well prepared for the chronic, co-morbidity patient,” Grignon said.

To address that, he said, Canada needs to better coordinate health care between settings, so people don’t fall through the cracks in the process. An emphasis on long-term care and home care would help, too. That’s something Grignon argues the federal government could help push.

“Some people who are now in nursing homes would be much happier at home, possibly cheaper.”

What does it mean for the federal election?

Not much, probably: It makes the federal Conservatives’ move to push back Canada’s retirement age to 67 look prescient, as that will save the feds pension dollars.

But it also may throw into question the wisdom of revamped formulas that tie federal health transfers to GDP, rather than, say, the needs of an elderly population.

But what does it mean for balanced-budget debates?

That question misses the point, Tombe says.

“As the population ages, it’s a no-brainer: Health care costs are going to grow; pension costs are going to grow. And you’re going to have to cover those increased expenses,” he said.

So the Canadian government has a choice: increase revenue to pay for the added cost of programs; keep revenue the same but run a deficit; or cut programs to rein in spending.

“The population aging is a slow-moving but very large issue,” Tombe said.

“It’s going to be less costly to adjust if action is taken now than if it is delayed until a budgetary crisis arrives.”

Comments