The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has done it again.

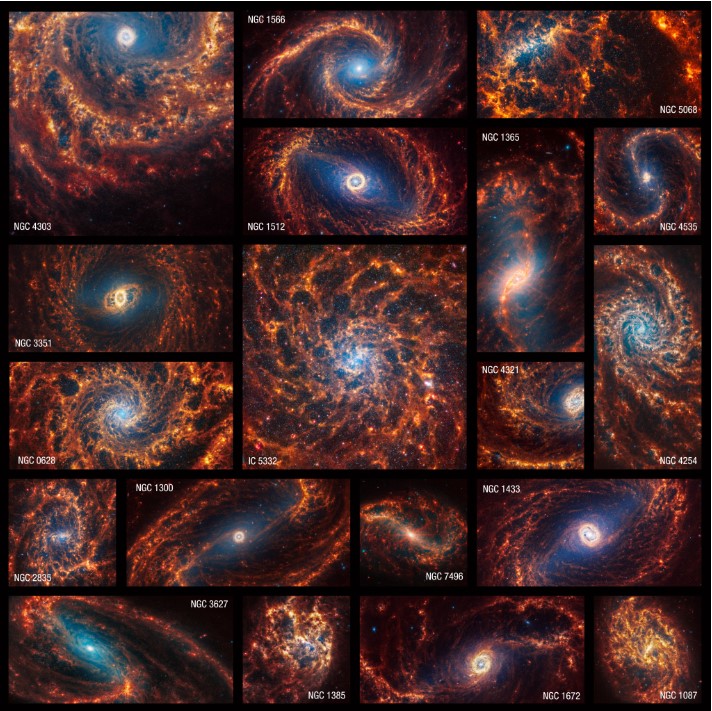

Astronomers and space enthusiasts around the globe are transfixed by a new set of highly detailed images put out by the telescope, capturing 19 spiral galaxies that are described as “mind-blowing.”

The observations were made as part of the PHANGS, or the Physics at High Angular resolution in Nearby GalaxieS, project.

The images show the Milky Way-like galaxies at the smallest scales ever observed outside our own galaxy.

“Webb’s new images are extraordinary,” said Janice Lee, PHANGS core member and a project scientist for new missions and strategic initiatives at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, in a statement. “They’re mind-blowing even for researchers who have studied these same galaxies for decades. Bubbles and filaments are resolved down to the smallest scales ever observed, and tell a story about the star formation cycle.”

Even to the untrained eye, the pictures are exceptional. Each new galaxy is teeming with swirling spiral arms laden with stars, and bright blue centres show off supermassive black holes or clusters of old stars.

The PHANGS project uses data from the James Webb as well as information from the Hubble Space Telescope, the European Space Observatory’s Very Large Telescope’s MUSE instrument and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile.

And while all these instruments, combined, allow astronomers to observe various wavelengths of visible, ultraviolet and radio light, the Webb’s unprecedented ability to zero in on infrared light allows astronomers to get a glimpse of the glowing dust surrounding the stars, and view stars that are still in the process of forming.

“We see the stars, kind of what you would think is in a galaxy, but we finally see the gas and dust starts to light up in the infrared wavelengths of light and that allows us to see this kind of previously hidden aspect of the galaxy in this amazing detail that was previously inaccessible and what we’re really finally understanding is how the gas and the stars interact,” Erik Rosolowsky, PHANGS core member and a professor of physics at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, told Global News.

“We can kind of see how they move back and forth and influence each other,” he added.

Get daily National news

The spiral galaxies captured by the telescope range in distance from 15 million to 60 million light-years away from Earth, Reuters reported.

The closest of the 19 galaxies is called NGC5068, about 15 million light years from Earth, and the most distant of them is NGC1365, about 60 million light years from Earth. A light year is the distance light travels in a year: 9.5 trillion kilometres.

According to NASA, evidence suggests that spiral galaxies grow from the inside out, meaning the stars appearing on the outside of the spiral are newest. Stars forming at the galaxies’ cores spread along their arms, spiraling away from the center.

“The farther a star is from the galaxy’s core, the more likely it is to be younger. In contrast, the areas near the cores that look lit by a blue spotlight are populations of older stars,” NASA explains.

And while research continues on the images, pink and red emanate from the galaxy cores in some of the photos, suggesting those colours may come from supermassive black holes, whose huge concentrations of matter weigh hundreds of thousands of times that of the Sun.

“Stars can live for billions or trillions of years,” Adam Leroy, a professor of astronomy at The Ohio State University in Columbus and a PHANGS team member, said in the statement.

“By precisely cataloging all types of stars, we can build a more reliable, holistic view of their life cycles.”

The JWST is the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, which has not only provided stunning images, but has also been vital in providing scientific knowledge about our universe and its origins since its 2022 launch.

The JWST has a much larger primary mirror than Hubble (2.7 times larger in diameter, or about six times larger in area), giving it more light-gathering power and greatly improved sensitivity over the Hubble.

At the time of its launch, scientists believed the telescope would be able to peer back in time, possibly to 100 million years after the Big Bang. And they predicted that not only would they we able to look back into galaxies from that time, but they also thought they might be able to determine the composition of those galaxies.

These new images prove that their predictions are getting closer to realization.

— With files from Global News’ Joe Scarpelli and Reuters

Comments