Canada is set to welcome nearly 1.5 million new permanent residents over the next three years, according to the new targets recently announced by Immigration Minister Marc Miller.

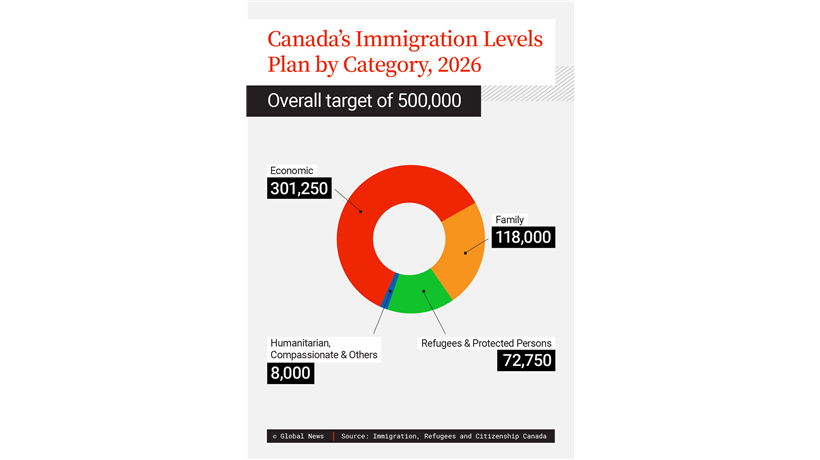

Canada does not foresee a cut to immigration levels and plans to hold its target of annual newcomers steady at 500,000 people starting in 2026, according to plans tabled in Parliament by Miller. A closer look at the data and breakdown by category can give an idea of who these new immigrants headed to Canada will be.

The Immigration Levels Plan sets guidelines and targets for how many permanent residents Canada plans to welcome under economic, humanitarian and family reunification streams.

The latest plan maintains previously set targets of welcoming 485,000 new permanent residents in 2024 and 500,000 new permanent residents for 2025. The number will stay at 500,000 in 2026 and “stabilize,” which Miller said is about “allowing time for successful integration” as well as “sustainable population growth.”

The total number of new permanent residents will be divided into four broad categories. These categories are economic; family reunification; refugees and protected persons; and one listed as “humanitarian, compassionate and others.”

So how many of each are set to come to Canada?

Economic migrants are projected to make up the largest chunk of newcomers, with 281,135 economic migrants projected in 2024 and 301,250 per year in 2025 and 2026.

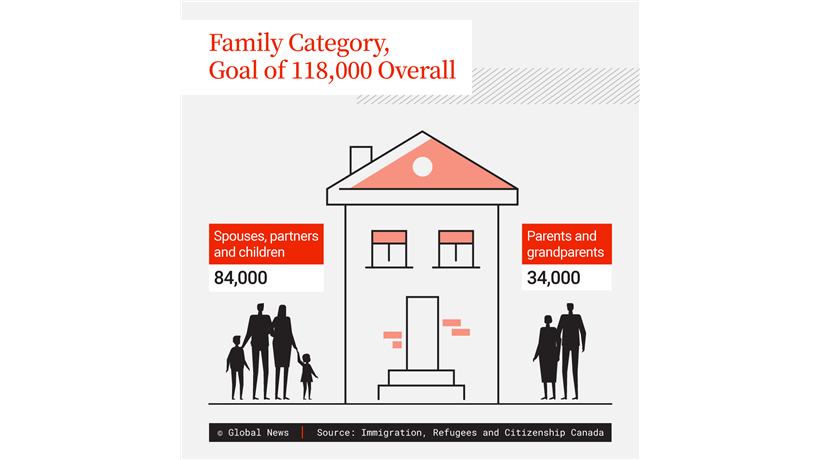

Family reunification numbers will also go up, from 114,000 in 2024 to 118,000 in 2025 and 2026.

The spouses, partners and children of Canadian citizens and permanent residents are expected to number 84,000 annually, while parents and grandparents are projected to be at 34,000.

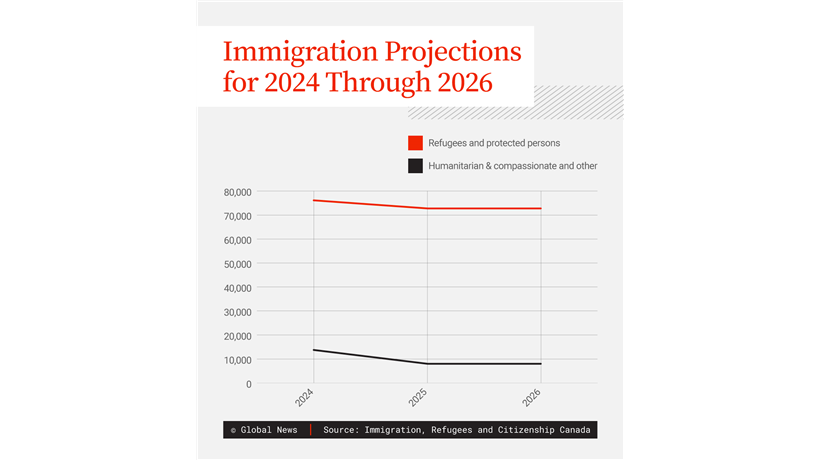

While the number of economic immigrants and family members will go up over time, newcomers in other categories are expected to go down. Even though the total number of new immigrants will go up, the number of refugees and protected persons that Canada welcomes as new permanent residents will go down from 76,115 in 2024 to 72,750 in 2025 and 2026.

Get breaking National news

The number of new immigrants welcomed annually under humanitarian and compassionate grounds will go down from 13,750 in 2024 to 8,000 in 2025 and 2026.

How does the economic category break down?

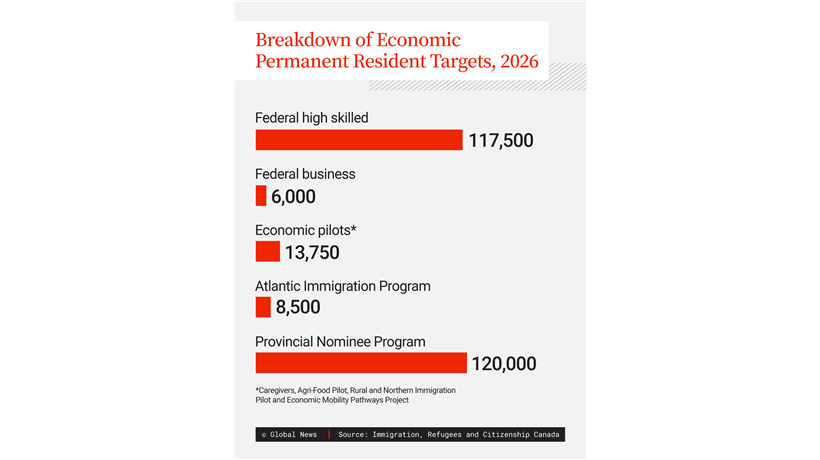

The economic category is broken into several sub-categories, with the largest number being assigned to the Provincial Nominee Program (PNP).

Under this program, the provinces can issue invitations to new immigrants to live there, based on their specific labour requirements. In 2024, 110,000 new immigrants will be welcomed under the PNP and 120,000 each in 2025 and 2026.

The Atlantic Immigration Program, which promotes settlement in Canada’s four Atlantic provinces, will welcome 6,500 people in 2024 and 8,500 each in 2025 and 2026.

Immigrants under the Federal High Skilled program will make up 110,770 new permanent residents in 2024 and 117,500 each in the subsequent two years. This includes The Federal Skilled Worker Program, Federal Skilled Trades Program, and workers with prior Canadian work experience.

Canada aims to issue 5,000 Federal Business visas in 2024 and 6,000 in each in 2025 and 2026.

The federal government, over the last year, has also launched several immigration pilots to boost workers in specific fields where Canada has a labour need. This includes visas for caregivers, health-care workers, agri-food workers as well as the Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot and the Economic Mobility Pathways Project.

In 2024, 10,875 visas will be issued under the category and in 2025, that number will go up to 14,750. In 2026, however, the number will go back down to 13,750.

The federal government also aims to promote francophone immigration outside Quebec.

In addition to the overall annual target of 485,000, Ottawa plans to welcome 26,100 French-speaking permanent residents outside Quebec in 2024.

That annual target would be 31,500 in 2025 and 36,000 in 2026.

Can immigration targets meet the moment?

Canada’s immigration strategy in the coming years will focus on aligning immigration policy with the country’s labour market needs, Miller said as he unveiled the strategic immigration review report in Ottawa.

The strategic review laid out a roadmap for Canada’s immigration strategy. It says Canada needs to attract global talent to fill its labour shortage and create a new role of a Chief International Talent Officer to try to match immigration policies with key labour needs including in housing and health care.

Meanwhile, Claire Fan, an economist at the Royal Bank of Canada, said Canada is massively underutilizing its current immigrant workforce.

An RBC report released in September, which Fan authored, said 30 per cent of immigrants to Canada with a degree in medicine, dentistry, veterinary medicine, or optometry worked in unrelated fields, compared to just 4.5 per cent of non-immigrants also educated for these fields.

For immigrants with foreign credentials and degrees, the barriers to entry are high including for those who have trained in specialties like medicine abroad.

“The current process to get them certified here, to be able to practice in Canada, is extremely difficult,” Fan said.

She added, “If you’re an immigrant who studied outside of Canada, there’s a 50-per cent chance that you work in a job that’s below what you actually train for.”

In an interview with Global News last month, Miller also recognized that Canada has filled much of its labour shortage by using temporary foreign workers.

“I think it’s important to realize that as a country we have become addicted to temporary foreign workers,” he told Global News.

Sarom Rho, who is the coordinator for MWAC’s student wing Migrant Students United, believes that to solve the issue permanently, Canada needs to create those pathways to permanent residency for migrant workers, including students.

“It’s international students who are on their bikes through the sleet and the rain, making food deliveries, who are working overnight, are handling packages at Amazon warehouses, all the while having to pay for extremely high tuition fees,” Rho said.

“International students are not just students, they are workers and they are migrants. And they face the same exploitations and denial of rights as other migrants do.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.