Decades before the infamous Salem witch trials, five women in Boston were hanged for witchcraft between 1648 and 1688.

Now, a group is dedicated to clearing the names of those women – and anyone accused, arrested or indicted for witchcraft in the state of Massachusetts in the 1600s and early 1700s.

Josh Hutchinson, leader of the Massachusetts Witch-Hunt Justice Project, told The Associated Press it’s “important that we correct the injustices of the past.”

“We’d like an apology for all of the accused or indicted or arrested.”

An online petition seeks 1,000 signatures asking Massachusetts state legislators to clear them.

“These innocent victims deserve better. They deserve to be remembered,” the petition reads.

This isn’t the first time the Witch-Hunt Justice Project has sought to clear the names of those persecuted in the past.

In May, legislators in Connecticut passed a resolution to exonerate 34 people accused of being witches in the 17th century.

The move came nearly 376 years to the day after Alice (Alsa) Young was put to death in the state, NPR reports. She was the first woman to be hanged in the gallows for alleged witchcraft in colonial America – a movement that would go on to see dozens of people, mostly women, put to death.

Twenty people were killed during witch trials in Massachusetts and hundreds more were accused. Nineteen were hanged and one man was crushed by rocks. Factors including superstition, misogyny, fear of disease and petty squabbles all contributed to the Puritan frenzy that was driving the Salem witch trials.

“We cannot go back in time and prevent the banishment, tarnishing or execution of the innocent women and men who were accused of witchcraft, but we can acknowledge the wronghoods they faced and the pain they felt, pain still recognized by their survivors today,” Sen. Saud Anwar, who introduced the bill, said at the time. “The Senate took an important step to own our state’s history and provide relief to the memories of the deceased and their descendants who still struggle with their ancestors’ wrongful treatment.”

Get breaking National news

Among those accused of witchcraft in Boston was Ann Hibbins, sister-in-law to Massachusetts Gov. Richard Bellingham, who was executed in 1656. A character based on Hibbins would later appear in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, published in 1850.

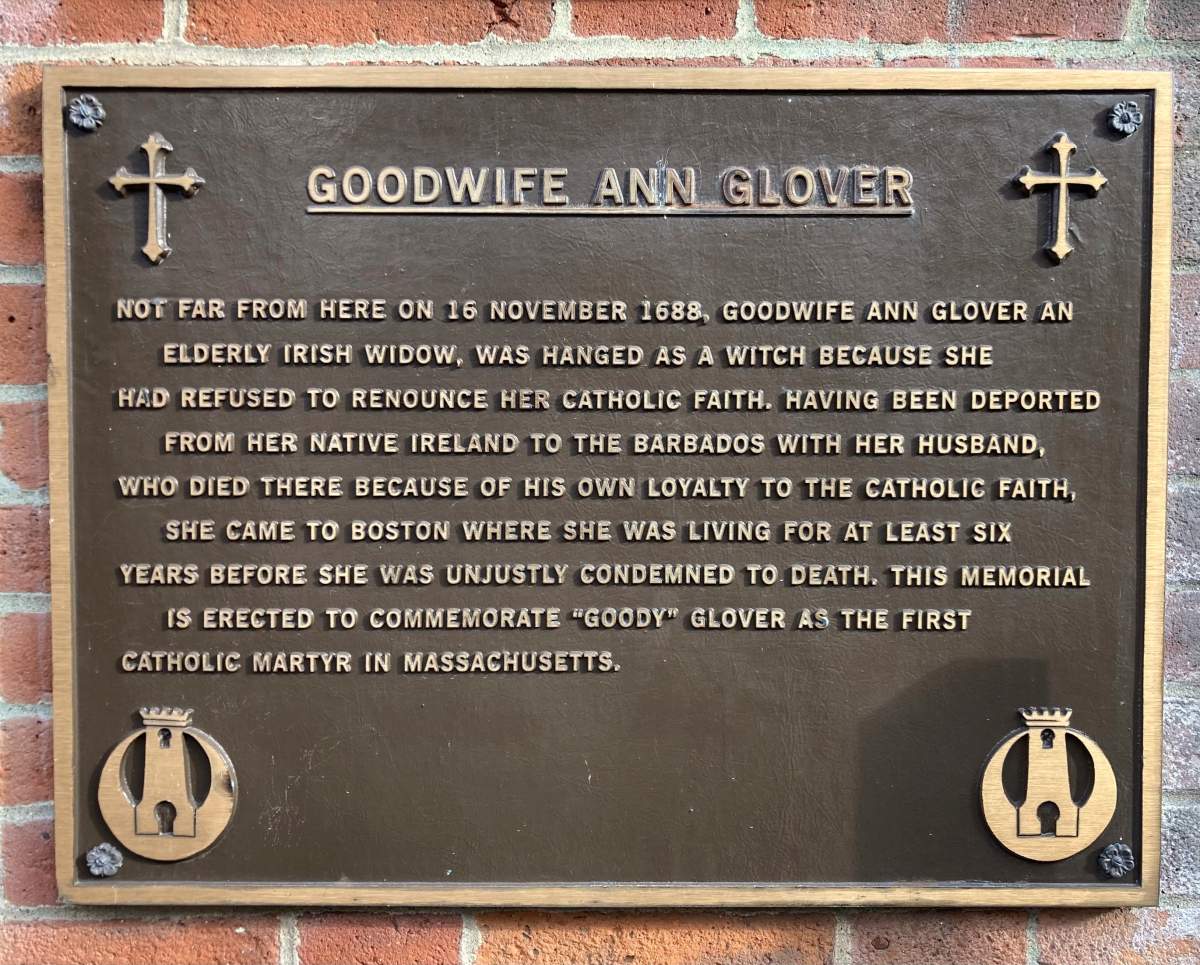

Another accused Boston witch, known as Goodwife Ann Glover or Goody Glover, was hanged in the city in 1688. A plaque dedicated to her is located on the front of a Catholic church in the city’s North End neighbourhood, describing her as “the first Catholic martyr in Massachusetts.” It’s one of the few physical reminders of the city’s witch trial history.

Massachusetts has already made efforts to come to terms with its history of witch trials — proceedings that allowed “spectral evidence” in which victims could testify that the accused harmed them in a dream or vision.

That effort began almost immediately when Samuel Sewall, a judge in the 1692-93 Salem witch trials, issued a public confession in a Boston church five years later, taking “the blame and shame of” the trials and asking for forgiveness.

In 1711, colonial leaders passed a bill clearing the names of some convicted in Salem.

In more recent years, Massachusetts has issued several apologies and signed bills exonerating specific women, but there are hundreds more who were never executed, instead cast to the fringes of society based on the accusations and testimony of others.

“During this dark chapter in history, these individuals suffered imprisonment, interrogation, loss of reputation, loss of income, separation from their families, illness, and death,” the petition states.

“Many of the Salem victims survived only because the governor instituted a new court with new rules after several months of executions had taken place. Before that, the court had a 100 per cent conviction rate. Meanwhile, those accused in the years before Salem have been all but forgotten.”

For many, the distant events in Boston, Salem and beyond are both fascinating and personal. That includes David Allen Lambert, chief genealogist for the New England Historic Genealogical Society.

Lambert counts his 10th great-grandmother — Mary Perkins Bradbury — among the accused who was supposed to be hanged in 1692 in Salem but escaped execution.

“We can’t change history but maybe we can send the accused an apology,” he told The Associated Press. “It kind of closes the chapter in a way.”

— with files from The Associated Press

Comments