As we head into Canada’s 44th federal election, some voters are wondering just how well — or badly — Justin Trudeau’s Liberals managed Canada’s finances through this historic crisis.

We know the federal government and provinces have run up big deficits, and most would agree at least some of it was necessary. But have Canadians gotten good value for their deficit dollar? Has all that spending kept households out of trouble and set us up for a strong post-pandemic recovery?

Normally, we would judge a government’s financial performance against previous governments. But that old comparison doesn’t tell us much; other governments didn’t face the situation Trudeau’s Liberals have seen over the past year and a half: A lockdown of the economy amid the worst pandemic in a century.

But we can compare Canada’s performance to that of other countries, particularly the world’s advanced economies. We can look at how much various governments spent, as a share of economic output, and how employment has looked since. That will give us an idea of how effective the spending was — how well it protected livelihoods in a crisis.

First, how much deficit spending did Canada do? At first, it looked disastrous. Last fall, projections from the International Monetary Fund showed Canada was on track to run the largest deficit, as a share of its economy, of any G20 country in the first year of the pandemic.

But things change rapidly in this crisis, and when the IMF updated its numbers this spring, Canada’s deficit came in far lower. Looking at the forecasts for 2020 and 2021 combined, Canada is still at the high end of debt accumulation, but no longer the biggest spender. That dubious distinction belongs to the United States.

“Canada still ran a relatively large general government deficit in 2020, suffering a sharper year-over-year fiscal deterioration than most (but not quite all) advanced economies,” said Warren Lovely, chief rates and public sector strategist at National Bank of Canada, who has been tracking these numbers since last year.

It wasn’t as bad as the initial forecasts because government revenue came in stronger than expected, and some of the spending the Liberals announced last year got pushed to the back-burner, Lovely explained.

Get breaking National news

That stands in contrast to the U.S., where stimulus spending has accelerated since the Democrats took control of Congress. The IMF forecasts the U.S.’s combined deficit for 2020 and 2021 to come in at a whopping 30.8 per cent of its annual economic output, compared with Canada’s 18.5 per cent.

Australia, Netherlands, Sweden get the most for their deficit buck

- Tumbler Ridge B.C. mass shooting: What we know about the victims

- ‘We now have to figure out how to live life without her’: Mother of Tumbler Ridge shooting victim speaks

- Trump slams Canada as U.S. House passes symbolic vote to end tariffs

- Mental health support after Tumbler Ridge shooting ‘essential,’ experts say

Essentially, if all this debt spending did what it was supposed to do, it will have saved people’s livelihoods.

Governments subsidized wages through programs like the Canada Emergency Wage Support (CEWS), meant to reduce layoffs. If it works, a program like this will reduce the unemployment rate in a crisis.

There were also expanded unemployment benefits, such as through the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) and Canada Recovery Benefit (CRB). Those programs ensure households can continue to spend — supporting other people’s jobs, if nothing else.

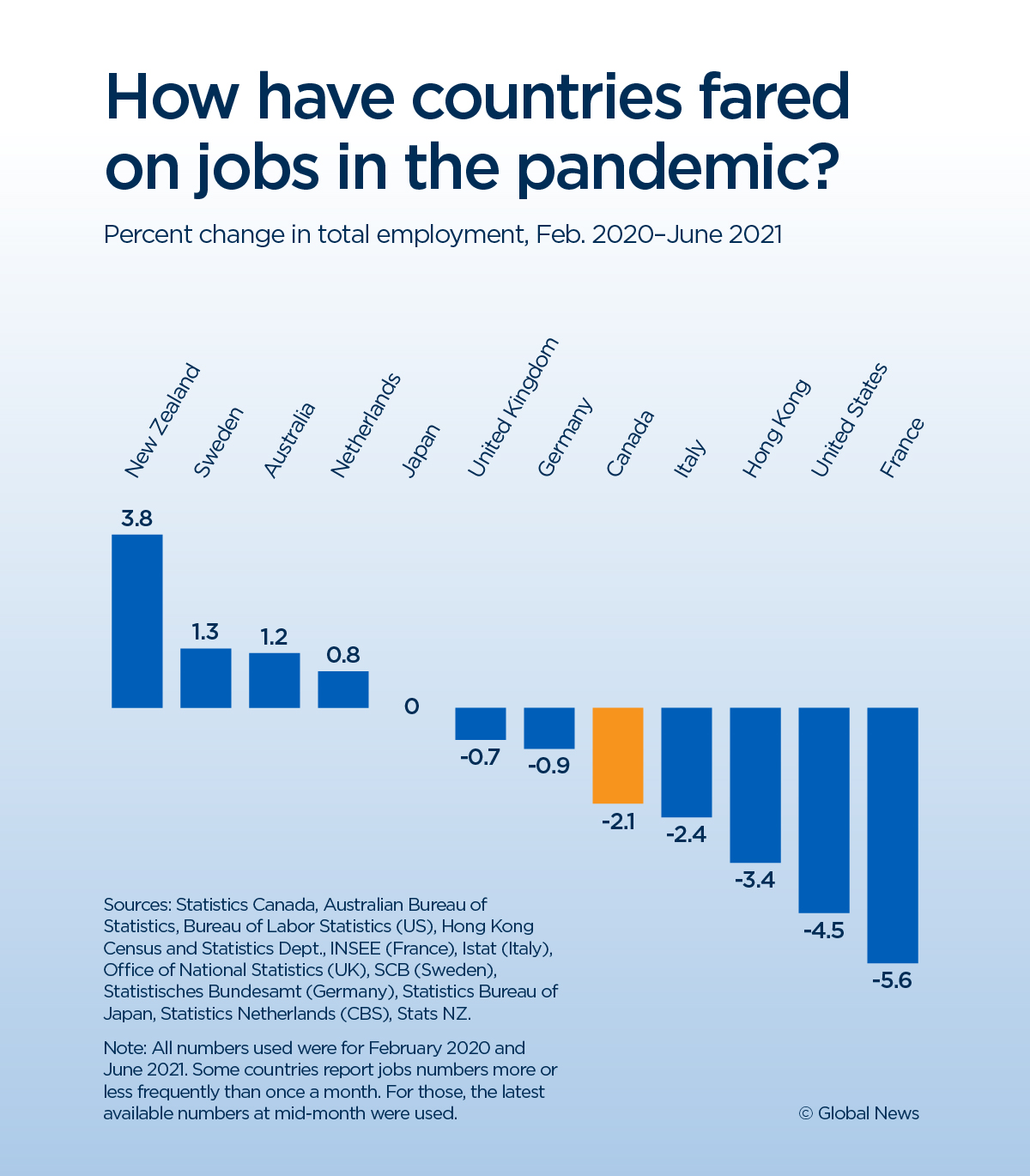

Whatever the strategy, success or failure can be measured most easily by the change in the number of jobs. On this measure, Canada doesn’t impress. We come in slightly below average for peer countries, with 2.1 per cent fewer jobs in June of this year than in February 2020, just before the pandemic was declared.

While that is not as bad as the U.S., which was down 4.5 per cent as of June, it pales in comparison with Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands and Sweden, all of which have more jobs today than before the pandemic.

Considering that these job-gaining countries also ran smaller deficits than Canada, we can clearly say they got the most bang for their deficit buck.

And no one seems to be getting as bad a deal as Americans, who are seeing the largest increase in deficit of any developed country, while suffering the second-largest job losses of any major economy, behind only France. This seems to have been a tag-team effort, with the weak job market and deficits beginning on Trump’s watch and continuing with the Biden administration.

There isn’t a clear relationship between pandemic strategies and economic performance. Australia and New Zealand’s harsh lockdowns stand in stark contrast to Sweden’s almost total lack of lockdowns, yet both have more jobs today than before the pandemic. In other words, leaving your country’s doors open for business in a pandemic doesn’t necessarily generate more jobs.

Note, too, that Australia and New Zealand have had among the smallest disease outbreaks among developed countries, while the Dutch and Swedish case rates are higher than Canada’s and among the top 20 worldwide. And yet, the economic outcomes are similar.

The verdict

So what can we conclude from this? There are two broad lessons for policymakers here: spending more money doesn’t always create jobs, and a temporary lockdown doesn’t always stifle your economy.

According to the Parliamentary Budget Officer, Canada’s financial path is sustainable, but the road to paying back the federal debt has grown much longer. Before the pandemic, the PBO forecast that Canada was on a path to eliminating its federal debt by the late 2040s. This has now been delayed to around 2090. Given that other countries spent less (often half as much) to get better results, it’s clear much of this increase in Canada’s long-term debt was unnecessary.

But the Liberals seem to have switched philosophies on public debt, from “deficits are necessary in hard times” to “it’s good for a government to run deficits any time.” There is a debate going on about this idea worldwide, but in Canada, the shift seems to have happened stealthily, under cover of a pandemic. It may be that we are seeing something similar in other countries as well, perhaps nowhere more so than the U.S.

But as far as pandemic response goes, the key seems to be smart, targeted spending. Going forward, whoever wins this election can feel comfortable taking the steps necessary to protect Canadians should another wave of COVID-19 break out — but those steps need not include hitting the panic button and breaking the bank.

After the hundreds of billions already spent in this crisis, the $610-million cost of our upcoming federal election looks like a drop in the bucket. And yet it’s somehow consistent, and telling, that the Liberals’ efforts to save their own jobs should come with a record-high price tag.

Daniel Tencer is an independent journalist whose work has appeared at HuffPost, Postmedia and elsewhere. He is based in Montreal.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.