Almost 30 years ago, Alice Sayant and her husband bought their first starter home in the suburbs of Winnipeg.

The newly built house was a 1,200-square-foot, three-bedroom bungalow with 1.5 bathrooms and a big backyard. The couple saved up for around five years to put a down payment on the $82,000 house.

“It was easier to get into a starter house then,” 68-year-old Sayant said. “We actually paid less than the asking price. There no bidding wars, so it was pretty common to put in an offer that was less than asking.”

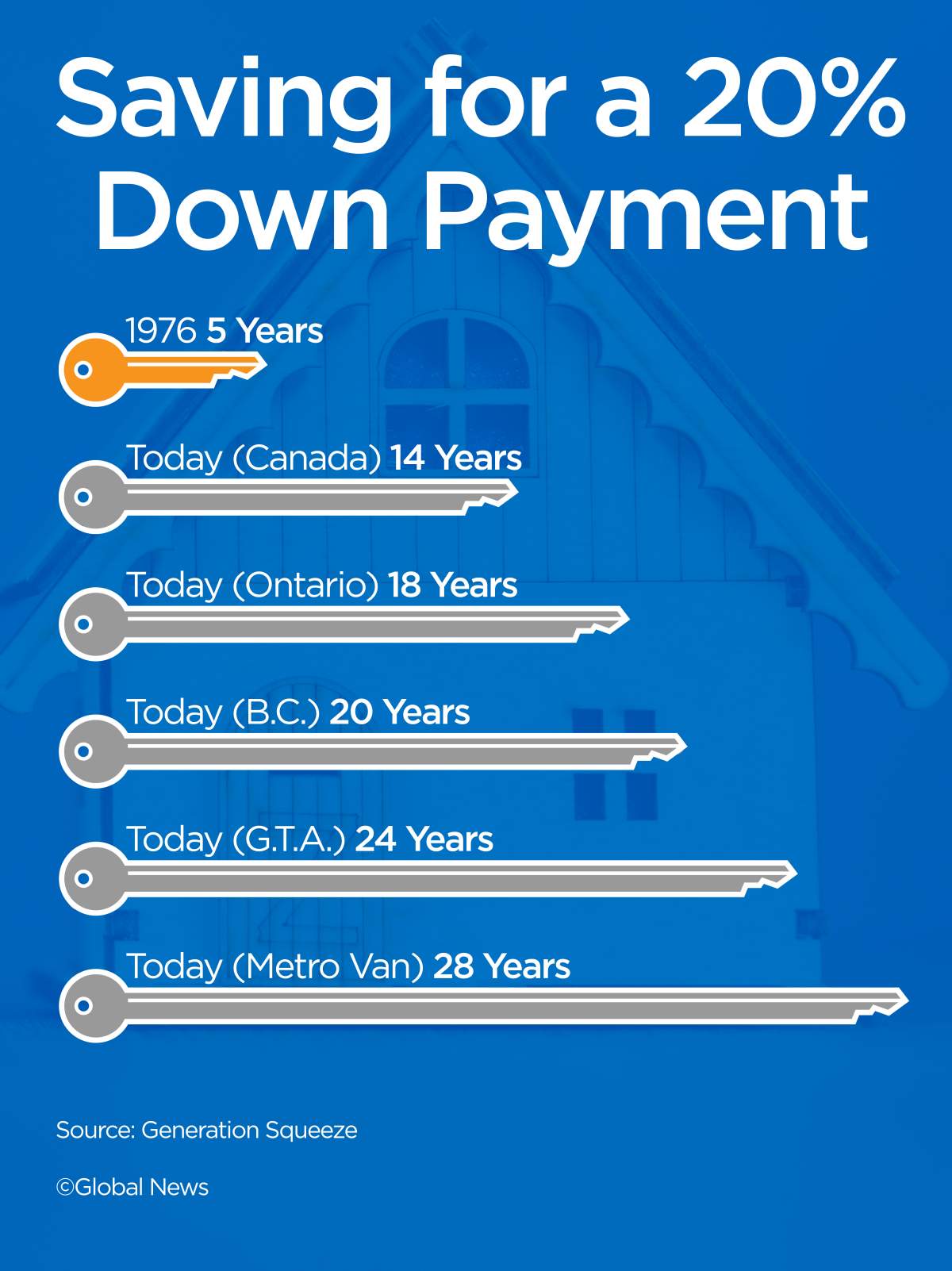

In 1976 — when the majority of baby boomers, born between 1946 to 1965, were coming of age as young adults — it took a typical young person five years of full-time work to save a 20 per cent down payment on an average-priced home in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), Metro Vancouver and many parts of Canada, according to Generation Squeeze, a non-partisan Canadian organization that advocates on behalf of young adults.

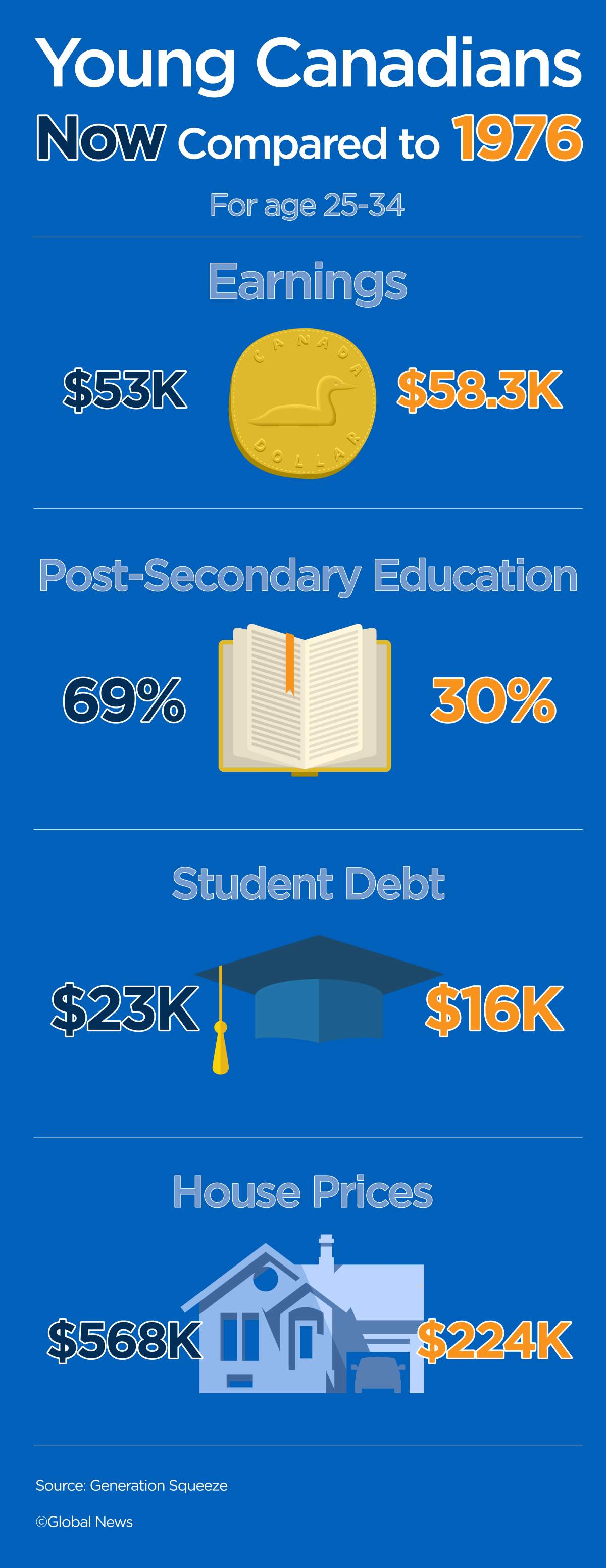

Flash-forward to today and home prices have skyrocketed while people’s earnings have lost ground relative to inflation by thousands of dollars.

For example, a millennial (someone born between 1981 and 1996) needs to work on average 14 years in Canada, 24 years in the GTA and 28 years Metro Vancouver to put a 20 per cent down payment on a house, according to Generation Squeeze.

“Hard work does not pay off like it used to,” said Paul Kershaw, founder of Generation Squeeze and policy professor in the UBC School of Population Health.

He started his organization a decade ago to shine a light on the lower earnings and rising housing costs that Canadians face. And since he founded Generation Squeeze, he said the problem for young people has only gotten worse.

“The reality for a typical young person is that they have to go to school longer, pay more for that privilege, to land jobs that pay thousands of dollars less and to face housing costs that are up hundreds of thousands of dollars, which drives up rent as well,” he explained.

“This causes the generation to have to delay starting their families. And when they finally decide to do so, the child-care cost is then near equivalent to another rent- or mortgage-size payment.”

He said this vice grip is tightened further by their growing debt.

For example, according to Statistics Canada, the median debt for millennials reached $35,400 in 2016, compared to $19,400 for young Canadians in 1999.

And according to a 2019 TransUnion report, Canadian millennials hold more than twice as much debt as any other generation.

“So people may think, ‘What am I doing wrong?’ But this is not an individual issue, this is a societal, economical and political issue,” Kerhsaw said.

Thirty-four-year-old Kathryn Checkley is no stranger to this struggle.

Checkley is a working professional living in Toronto as a renter with her husband and baby. She said she’s tired of renting and dreams about owning a house, but feels priced out of the market in the GTA.

“I’m one of those people who loves checking Zillow and Realtor.ca, just to see what’s out there and dream a bit,” she said.

“At this point, we would have to win the lottery in order to afford a house in the GTA.”

She and her husband have talked about moving further out of the GTA in order to afford a house, but her husband is an occasional teacher with the Toronto District School Board and would lose his seniority if he moved to another district.

“And I would likely have to commute to Toronto for work, so we would add on the expense of a car, transit passes, gas and insurance. It’s not clear that we would be any better off if we did manage to find a home further away,” Checkley added.

Some of the issues she’s been facing with affordability are paying off student loans, not relying on parents or grandparents for financial support and salaries that have not kept up with the price of inflation.

Her husband also relies on contract teaching work and she was a professional in the non-profit sector, which “tends to offer lower salaries than corporations.”

In 2017, Checkley made the switch to the corporate working world in the hopes of more stability and higher earning potential.

“But in March of 2020, I was laid off due to COVID while in my first trimester with my first baby,” she said.

“So it feels like we’ve just never had a sustained amount of time with both of us working full-time and consistently able to save for a home. COVID knocked us back again, as we both had to take the CERB to make ends meet.”

How did it get this way?

Millennials like Checkley have been accumulating less and less wealth over the past 30 years.

When baby boomers hit a median age of 35 in 1990, they collectively owned 21 per cent of the wealth in the U.S., according to the U.S. Federal Reserve.

Get weekly money news

When Generation Xers (born between 1965 and 1980) reached 35 in 2008, they owned nine per cent nation’s wealth. And in 2020, millennials owned 4.6 per cent of the nation’s wealth.

Kershaw called this a “snowball effect” of young people unable to get their foot in the door.

Because of this struggle, many young Canadians have to rely on their parents or grandparents for financial support when purchasing a home.

While there’s little hard data on exactly what percentage of first-time homebuyers nationwide are receiving help from their family, a 2017 poll by financial products comparison site Ratehub.ca, found that 43 per cent of millennial homebuyers had financial help.

“And the harder it is to kind of get that start at the beginning, the harder it will be to kind of continue on … so that there are more people going to post-secondary, but then it’s more difficult to get a job with a degree and then there are more student loans. And then you get into housing, child care. I think there’s a lot of different pieces that add up,” Kershaw said.

In terms of housing, the reason many young Canadians cannot afford a home is that policymakers have tolerated escalating prices far beyond what a young person makes, Kershaw argued.

For example, Sayant and her husband both worked full-time and she said they didn’t have to “scrimp” to get by, their salary was able to cover the mortgage and they even had savings left over to put into retirement.

“It was very much easier at that point to be independent, nobody would ever think about moving in with your parents or even taking money from their parents,” Sayant said. “I think probably it was easier to get a job too.”

Of course, housing in the 1970s and early 1980s wasn’t perfect. Sayant said her mortgage was 18.5 per cent due to the high interest rates at the time. However, with interest accumulating on money, she was still saving in her bank account.

Despite the high interest rate at the time, Kershaw said those who got into the housing market at the right time, such as Sayant, have seen a significant increase in net worth.

“But it’s the opposite for those who didn’t,” he said.

“We have tolerated rising home prices because it has made homeowners who got into the housing market earlier get rich while we sleep, watch television and cook.”

Kershaw said he bought a home in Metro Vancouver in 2004, and over the last decade has “made more money from my home price going up than and I did as a hard-working professor who works day to day.”

The divide, where the wealthiest in the country benefit from housing price gains and depend on their rise for retirement savings and wealth accumulation, will affect Canada’s ability to create jobs and grow the economy in the long run, he warned.

He blames some of the housing crisis on politicians who are not willing to adjust the housing system to ensure prices stay on par with what people earn.

“We are spreading the contagion of unaffordability not simply because of some mean-spirited foreign buyer or because of some greedy real estate agent,” he said.

“We are spreading the contagion of unaffordability because many Canadian households are entangled by policies that incentivize them to hope that home prices will rise.”

Since the Trudeau government came into power in 2015, the party has put initiatives in place to help with soaring housing costs.

Tougher mortgage stress-test rules began June 1 (which aimed to cool the market), a national empty homes tax was announced in November 2020, and funding has been dedicated to building social housing.

The empty homes tax proposal, which if passed would take effect in January, would penalize homeowners who are not Canadian citizens or permanent residents, making them pay an annual tax of one per cent of the value of residential real estate that is considered vacant or underused.

But critics say the measures don’t do enough to tackle the growing problem.

National statistics show the average national home price is now more than seven times the average household income, according to data from the Canadian Real Estate Association (CREA) and Statistics Canada.

For more than a decade, home prices growing much faster than incomes was an issue largely limited to Vancouver and Toronto, two of the country’s priciest and most active real estate markets.

In Greater Vancouver, the average price of a home was close to 12 times the average local income in 2016, according to data from the Canadian Real Estate Association (CREA) and Statistics Canada.

But the current housing extravaganza is dramatically widening the gap between home prices and incomes in a number of markets across Canada, the data shows.

In Ottawa and Montreal, for example, the average home price is now around six times local household incomes.

“There’s a pressure politically not to change what’s underway in the current system, which is making those who got into the system earlier better off,” he said.

Tack on child care to the monthly bill

It’s not just housing that creates financial barriers for millennials, the high cost of care is a major issue for Canadian parents.

According to a 2016 report from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Canadian families spend almost one-quarter of their income on child care — a much higher ratio than other OECD members.

The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) has found that the cost of child care in Canada is rising faster than inflation. And a 2018 survey by accounting and advisory services firm BDO Canada, found that one in five millennials are actively delaying having children because they feel they can’t afford a family.

Of course, millennials’ approach to family is different than it was for baby boomers, Kershaw said, as there are more dual-income earners than ever before — heightening the need for child care.

For example, 2016 research for Statistics Canada shows that the percentage of families with two parents working outside the home had doubled in the 40 years between 1976 and 2015.

And as dual-income families have become the norm, child care has only become more expensive, especially over the last decade. In some cities, including Toronto and Edmonton, the cost of child care rose as much as 20 per cent between 2014 and 2017.

But child care was not much of an issue for the baby boomer generation, Kershaw argued, saying there wasn’t a strong “feminist commitment” to women working in the labour market.

“Baby boomer women were winning that battle for us, so we owe them that debt,” he said.

Also, for the baby boomer generation, one parent could bring in a salary that was much more in line with the cost of housing, so there was not as much pressure for dual-income earners, he added.

But now the massive gap between home prices and earnings has promoted a need for child care “more than ever,” he said.

To address the rising costs, in April the federal government proposed up to $30 billion in fresh spending over the next five years to create a nationwide child-care system that it promises will bring child-care fees down to an average of $10 per day in regulated child-care centres by 2025-26.

COVID-19 pandemic didn't help

Historically low mortgage rates, a race for space and a rush to get into the market ahead of tougher borrowing rules have all fuelled a surge in home prices during the coronavirus pandemic.

Oksana Kishchuk, a consultant at Abacus Data, a polling and market research firm based in Ottawa, said she and her partner have been watching housing prices rise around the city, leaving young Canadians like her priced out of the market.

Before the pandemic, she said wages were already not in line with rising inflation. But when COVID-19 hit the world economy, some people at the top moved up the financial ladder while others fell to the bottom.

Housing is a perfect example of this, she said.

“Housing has become a piece of the conversation that is the epitome of what boomers have and millennials don’t,” Kishchuk said, adding that COVID-19 just made it worse.

The pandemic shift to working from home coupled with rock-bottom mortgage rates and government aid drove up housing prices around Canada (and the world).

As of April, home prices nationwide were up 23 per cent compared to the same month in 2020, according to the Canadian Real Estate Association (CREA).

And the real estate frenzy that has long been the norm in Toronto and Vancouver has hit smaller cities, too, like Halifax, Nelson, B.C., and Winnipeg.

In April, home prices in Halifax reached record heights, with selling tactics like under-listing a house to attract multiple offers, bidding wars and people buying houses sight unseen becoming increasingly common.

The situation has pushed the average price of a home in Halifax up nearly 35 per cent in March compared to the same time in 2020, according to the CREA.

What can be done?

Both Kershaw and Kishchuk said unless there are major policy changes in the upcoming years, housing will continue to squeeze generations out of the market.

“There should be policies in place that allow for younger people to see their housing dreams more achievable, such as enabling more housing to be built,” Kishchuk said.

She argued that the reason a lot of affordable housing policies may not be currently in place is that young people don’t vote as much as older generations.

“Their voice isn’t heard as much and they don’t have as much power with their dollars against kind of thing,” she said.

However, she said that it is a dangerous view to fall into, as population-wise, the millennial generation is quite big. And the more the generation grows older, the more it will accumulate wealth and power.

“And to ignore the generation for the first 20 years of their adult life could be very dangerous when they get to be in that baby boomer age,” she said.

Kershaw said until “we break our addiction” culturally, politically and economically to rising home prices, there’s little chance that we will succeed in stalling home prices and letting earnings recouple.

Although there is no silver bullet to restore housing affordability, he said there are enough “tools in our toolbox” to achieve the goal.

For example, Generation Squeeze recommends restricting global capital flows into local real estate, eliminating hidden ownership and incentivizing households to put more of their retirement and other savings into non-housing investments.

His advice to young people who have seen their dreams of homeownership dashed during the pandemic is not to blame themselves for what is happening around them. In his view, they are collateral damage. They may have to wait it out until homeowners are willing to make concessions.

“We have to change our hearts and our minds about ‘not in my backyard.’ We need to welcome more renters and co-ops in our neighbourhoods,” Kershaw said. “Those policy and cultural shifts need to happen side by side.”

— With files from Erica Alini and Anne Gaviola, Global News

Comments