A new study by researchers at the University of Waterloo shows how quickly the ecosystem of the Rocky Mountains in Western Canada has shifted.

Titled “A century of high elevation ecosystem change in the Canadian Rocky Mountains,” the project was led by University of Waterloo Prof. Andrew Trant.

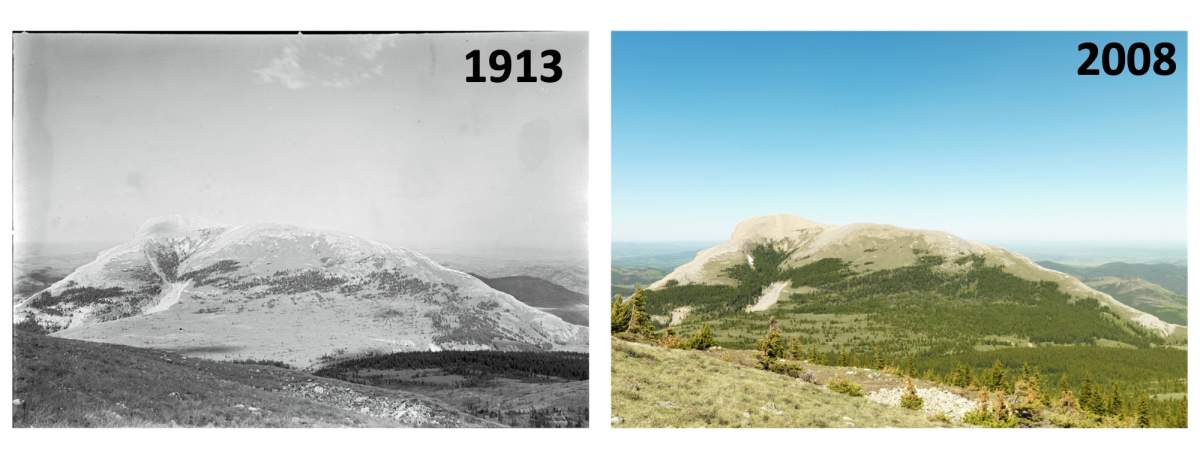

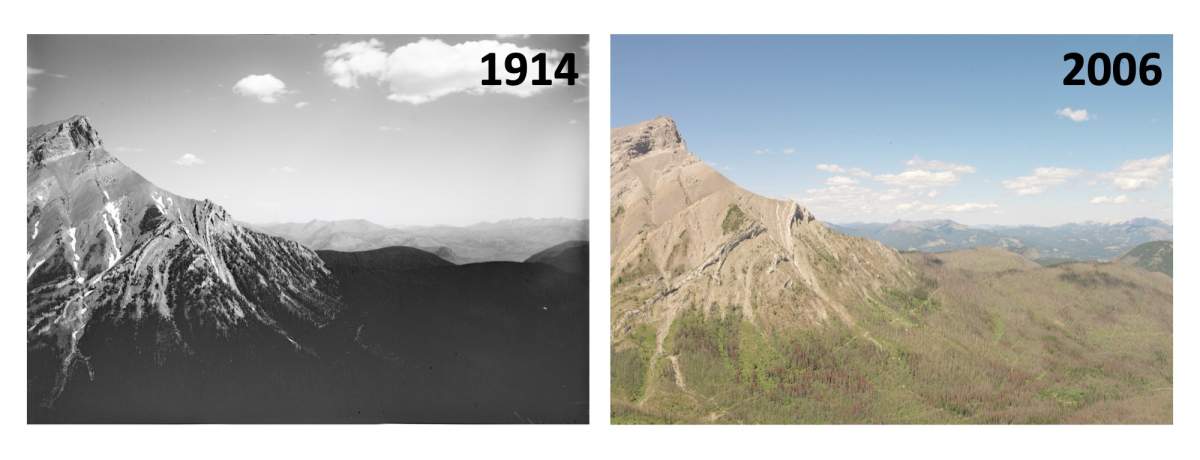

His team of researchers compared 81 before and after photographs, which were between 68 and 125 years apart, to compare how mountain habitats had changed by tracking treelines and tree density.

“We found that the Canadian Rocky Mountains have undergone a dramatic shift over the past century,” Trant said in a release. “By comparing the photographs from the late 1800s to ones taken today, we found widespread evidence of ecosystem change by tracking treeline advance and increases in tree density.”

Trant said the researchers were able to glean invaluable research from the study.

Get daily National news

“Working as an ecologist, this analysis is invaluable for providing conservation targets and measuring ecosystem disturbances from climate change,” he said.

The study found evidence of treeline advance, increases in tree density and that changes in the growth form of trees showed them to be more erect.

“These results show just how quickly and drastically our ecosystems are changing in Canada,” Trant said.

“This work shows the value of historic references, which are invaluable for our understanding of ecological change over time, particularly in mountain ecosystems, which are sentinels of change.”

The study was published in the June 2020 edition of Scientific Reports.

From the 1880s to the 1950s, the Geological Survey of Canada and the Dominion Land Survey sent teams into the Rockies to develop maps in use today. The crews took carefully annotated, high-resolution photographs everywhere they went — 120,000 of them, now the largest such archive in the world.

“There’s this huge, huge reserve,” Trant told the Canadian Press. “They occupy rooms and rooms.”

Since the 1990s, teams have been going back into the field and rephotographing the same scenes. There are now more than 8,000 image pairs.

Because the early photos were taken with the best equipment of the day — from large view cameras with glass-plate negatives to high-quality Hasselblads — they permit detailed comparison with the modern images. Researchers were able to zoom in on single trees.

*With files from Canadian Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.