U.S. politicians are proposing tax reforms that they say will be a “Better Way.”

But they could represent a worse one for Canadian exports to the U.S., which make up one-fifth of the Great White North’s economy, CIBC economists Avery Shenfeld and Benjamin Tal wrote in a Tuesday report.

“To paraphrase Michael Jackson, it’s bad, it’s bad, you know it,” they wrote.

But there are ways that Canada and other U.S. trading partners can fight back, they added.

READ MORE: Donald Trump, Paul Ryan look to tax products coming into the U.S.

In a report titled, “The Border Adjustment: Gauging the Threat,” the economists talk about a tax reform plan being pushed by U.S. House of Representatives Speaker Paul Ryan.

The plan carries a few reforms, including the following, as outlined by CIBC:

- Lower personal tax rates

- Dropping the corporate tax rate from 35 per cent to 20 per cent

- A possible 20 per cent tax on imports — separate from the idea that’s been floated to pay for the wall with Mexico

- No taxes on export revenues

The reforms form something of a contrast with plans that have already been announced by U.S. President Donald Trump.

Trump has said he wants to drop the corporate tax rate even further than Ryan does — from 35 per cent to 15 per cent.

Get weekly money news

Either plan would pose challenges for Canadian companies, which would have more difficulty attracting high-skilled talent, CIBC noted.

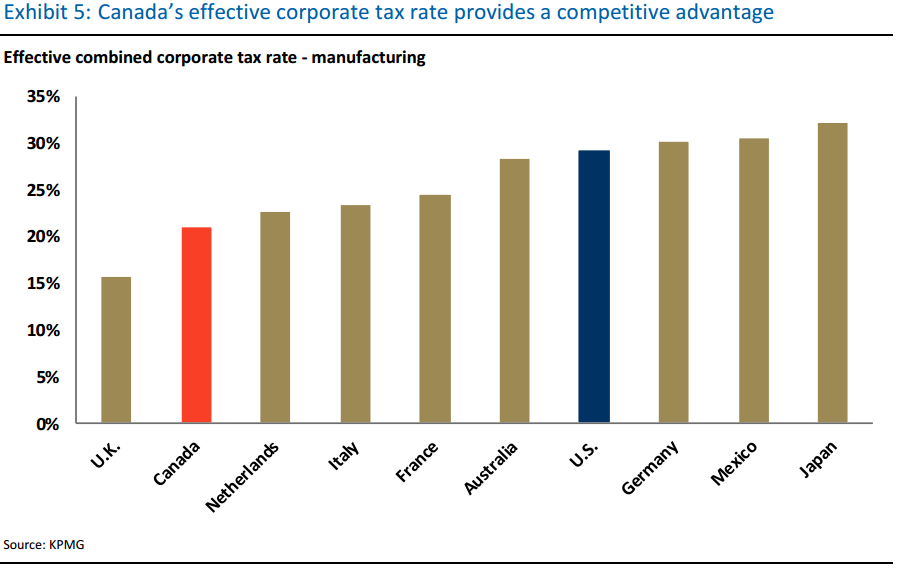

Canada currently enjoys a corporate tax advantage that could be wiped out with Trump’s proposal, said a September report from RBC:

There are, of course, many uncertainties when it comes to the impacts that both Ryan and Trump’s tax plans would have on Canada’s economy.

But the economists leave little question that a tax on imports from Canada or other countries could take a financial toll.

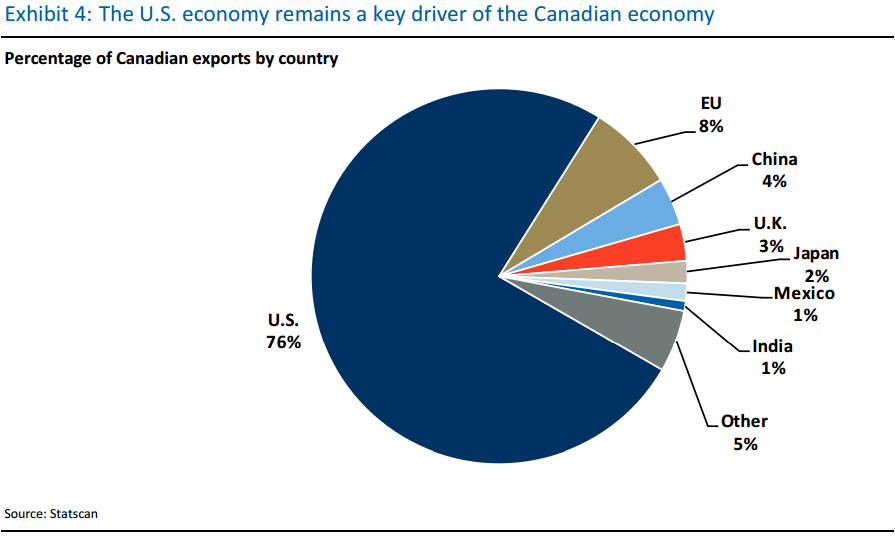

This chart, also from RBC, shows how Canadian exports to the U.S. compare to other trading partners:

Sectors that would suffer most from Ryan’s tax reform plan include export-oriented industries such as computers, chemical, machinery and transportation equipment, Shenfeld and Tal noted.

The changes proposed in “Better Way” could also motivate companies to leave Canada and relocate south of the border, Shenfeld and Tal wrote.

But quantifying precisely how bad these measures would be for Canada is a difficult task, they added.

Evaluating the potential impacts of these changes would require consideration of several factors.

That includes the falling value of the Canadian dollar, competitive challenges arising as a result of the tax reforms, and monetary policy set by the Bank of Canada, among other things.

“The truth is that nobody can model such a change with any degree of credibility,” Shenfeld and Tal wrote.

Fighting back

The measures contained in “Better Way” don’t represent the first time that a new border tax has presented potential issues for America’s trading partners.

In 1930, the U.S. enacted the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, which imposed a 20 per cent tax on imports, Shenfeld and Tal noted.

Canada led a number of countries in retaliating against the U.S.; it imposed a tariff on U.S. exporters, stalling global trade and creating “just one more factor in a deepening Great Depression.”

The names Smoot and Hawley have since gone down in “economic infamy,” Shenfeld and Tal wrote.

But there are more recent examples of countries retaliating against the U.S..

In 2009, the United States imposed import duties of 35 per cent on Chinese tires in response to a surge in tire exports that hurt the U.S.’s own industry, The Wall Street Journal reported.

China then targeted U.S. exports by stepping up imports of other products from countries besides the U.S.

“In the end, American exporters could be left worse off in an all-out trade war, despite initially benefiting from the tax-exempt status of export revenues,” Shenfeld and Tal said.

Comments