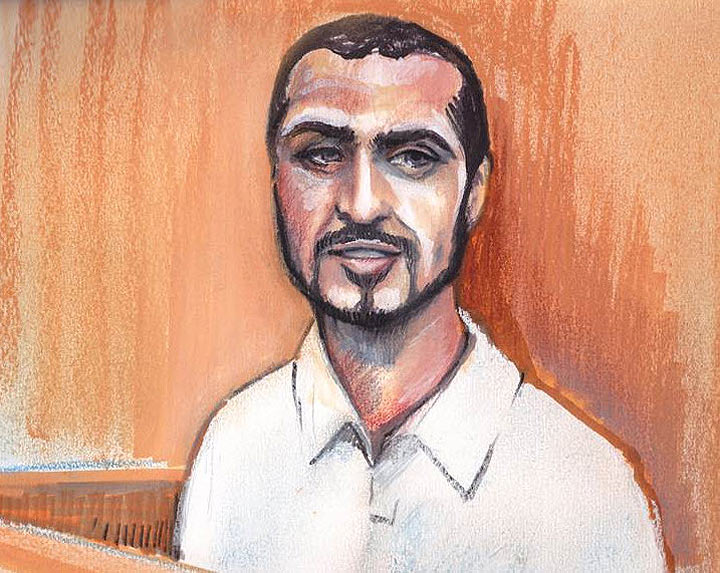

Former Guantanamo Bay prisoner Omar Khadr is set to appeal his five war crimes convictions on the grounds that the military commission had no legal authority to try him or accept his guilty pleas.

Speaking from Rosslyn, Va., Khadr’s U.S. lawyer told The Canadian Press the main argument turns on whether what Khadr is accused of doing as a 15 year old in Afghanistan was in fact a war crime under American or international law.

“These things weren’t crimes, at least in 2002. They weren’t crimes at the time of the charged conduct,” said Sam Morison, a civilian lawyer with the U.S. Department of Defense.

“Even if you take the government’s allegations at face value, he still didn’t commit a war crime.”

The most serious charge against Khadr arose out of the death of an American special forces soldier in the heat of a vicious battle at an Afghan compound in July 2002.

The basis for charging the Toronto-born Khadr, now 27, for the battlefield death was that he was not in uniform, and was therefore an “unprivileged combatant.”

Khadr’s lawyers argue there is no authority under international law to elevate what Khadr did to the status of a war-crime, which includes such egregious acts as deliberately targeting and killing civilians as the 9/11 terrorists did.

“Merely being an unlawful combatant is not by itself a war crime,” Morison said.

- Life in the forest: How Stanley Park’s longest resident survived a changing landscape

- Bird flu risk to humans an ‘enormous concern,’ WHO says. Here’s what to know

- Roll Up To Win? Tim Hortons says $55K boat win email was ‘human error’

- Election interference worse than government admits, rights coalition says

“War crimes still have to be war crimes. It has to do with what you do.”

Khadr’s arguments invoke recent successful appeals by others convicted in the widely maligned military commission system.

A year ago, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit threw out a conviction against Salim Hamdan, driver for terrorist mastermind Osama bin Laden. The court held that material support for terrorism was not a pre-existing war crime at the time of Hamdan’s actions.

The same court made a similar ruling in January in the case of Ali Hamza al-Bahlul, who did media relations for bin Laden.

“If it turns out that these weren’t crimes within the jurisdiction of the commission, then the judge didn’t have the authority to accept the plea and it’s void,” Morison said of Khadr’s case.

While Khadr appears to have given up his right to contest his conviction under the plea deal, Morison said military commission authorities didn’t follow the appropriate appeal-waiver law.

His lawyers argue Khadr pleaded guilty to get out of Guantanamo, given that he faced indefinite detention even if he had been acquitted.

The appeal makes prominent note of Khadr’s juvenile status at the time of the events, and his subsequent mistreatment by his captors after he was found horribly wounded in the rubble of the compound.

Khadr, blinded in one eye, still suffers the severe after-effects of his injuries, including problems that could blind his other eye and a chronically infected shoulder.

Morison, who will be speaking about the case at the University of Alberta in Edmonton on Tuesday, said he expected to formally file the appeal before the Court of Military Commission Review in Washington, D.C., on Friday.

The case is expected to be heard in the spring but it’s unlikely the ruling will be the last word on Khadr’s U.S. file.

After eight years in American custody, Khadr was convicted in a plea agreement in October 2010 and sentenced to eight more years. He was transferred to Canada in September 2012 to serve out his sentence and is currently a maximum security prisoner in Edmonton.

His Canadian lawyer, Dennis Edney, confirmed Thursday he has filed an appeal against a recent Alberta judge’s ruling that Khadr has been properly incarcerated as an adult in a federal penitentiary.

A spokesman for Public Safety Minister Steven Blaney repeated his previous comments:

“The government of Canada will continue to vigorously defend against any attempt to lessen his punishment for these crimes.”

Morison was unimpressed.

“That’s pretty mind boggling,” he said.

“If the conviction is thrown out, on what grounds would they keep him in jail?”

_ With files from John Cotter in Edmonton.

Comments