Metro Vancouver: it’s a region of nearly 2.5-million people, spread over a land mass of over 2,880 kilometres.

It’s a place where politicians are set to go to the polls in just over a month’s time, at a time when “crisis” describes the state of living there.

Coverage of Vancouver housing affordability on Globalnews.ca:

Candidates have hit the hustings with pitches aimed at improving “affordability,” with ideas such as building more homes and reducing red tape at city hall.

But data compiled by Global News shows just how far most of the region has to go before the housing in many communities can be called “affordable.”

For families earning median incomes, the data provides the latest evidence of a region where the dream of owning a single-detached home has gone to die.

And while there remain communities where median-earning families have a choice of apartment or townhouse, the price of living in the latter can carry a cost that goes well beyond a monthly mortgage payment.

READ MORE: 4 charts that show how foreign buyers’ taxes can yank prices down in Vancouver, and elsewhere

Global News took home price data from the Greater Vancouver and Fraser Valley real estate boards for August 2018 and ran them through a calculator to determine just how much money a family needs to earn to qualify for a mortgage across the region.

In doing so, Global News factored in expenses such as property taxes (including the basic homeowner grant where it applies), heating costs, strata fees and monthly personal debt payments.

These numbers were then twice run through an intelliMortgage calculator with a 20 per cent down payment, a 30-year amortization and a qualifying interest rate of 5.44 per cent.

Then, they were compared against Census 2016 data showing median total incomes for economic families with children.

(More detailed methodology is available at the bottom of this story.)

Click the points on the map below to see how much money a household must earn to qualify for a mortgage in each of these areas:

- Red markers denote areas where median family incomes cannot qualify for mortgages for benchmark-priced single-detached homes, townhomes or apartments

- Yellow markers denote areas where median family incomes cannot qualify for mortgages on benchmark-priced single-detached homes or townhomes

- Blue markers denote areas where median family incomes can still qualify for mortgages on townhomes and apartments

There isn’t one municipality in Metro Vancouver where a median family income can qualify for a mortgage on a single-detached home, according to these calculations.

In East Vancouver, for example, the income needed to borrow money to buy a single-detached home is over $230,000.

That’s more than double the median family income for the City of Vancouver — $111,636.

The lowest income needed to service a mortgage on a single-detached home is in Maple Ridge, where it’s $150,032.

There’s only one community where median family incomes are high enough to support that — the District of North Vancouver, where the median family makes $156,971.

READ MORE: Interest rate hikes wiping out housing affordability gains in Vancouver — report

Townhome prices didn’t provide much relief across most of Metro Vancouver, either.

Of 30 areas covered in real-estate board data, median family homes could support townhouse mortgages in fewer than 10 of them.

The gap to own a townhouse was highest in Vancouver West, where it was over $85,000. In Richmond, it was over $50,000.

Even in Coquitlam, about 30 kilometres away from Vancouver’s city centre, the gap was nearly $15,000.

There were also six areas where median family incomes couldn’t qualify for mortgages on benchmark-priced apartments: the Vancouver West region, which includes downtown; Richmond; West Vancouver; Burnaby East; Burnaby North and Burnaby South.

They represented six areas where the median total family income couldn’t support a benchmark-priced home of any type.

Metro Vancouver’s affordability fades even further when you look at which homes a household could qualify for on the median family income for the entirety of the Vancouver Census Metropolitan Area.

The following map looks at homes that income level could qualify for (home value of $461,552), according to calculations done through Ratehub.ca (Map by Andy Yan/Community Data Science at SFU City Program):

Rob McLister, founder of mortgage comparison site RateSpy.com noted that the issue of qualifying for a mortgage doesn’t necessarily cut across all buyers.

He told Global News that “countless local households of average income can indeed qualify for a mortgage in Metro Vancouver because price appreciation has granted them considerable equity.”

“Purchase affordability is more of a challenge for first-time buyers, current renters and outsiders wanting to get into the Greater Vancouver housing market,” he added.

Nevertheless, there are challenges for those who wish to buy, even some distance outside the City of Vancouver.

‘Drive ’til you qualify’

“This is the most depressing sheet I’ve seen in a long time,” said Andy Yan, director of Simon Fraser University’s (SFU) City program.

For him, it hit home the “futility of existing in Vancouver.”

“If you accept that single-detached homes are no longer attainable for over half the population, what’s the alternative?” he asked.

“You similarly go into the ones that are supposed to be the response, whether it’s townhouses or condos, and you find that similarly has its limitations.”

Yan said North American cities have embraced an ethos of “drive ’til you qualify” — an idea that the further you drive, the easier it will be to find a home you can afford to buy, and from which you can commute to work.

People who work in Downtown Vancouver, for example, might look to buy a home in a city like Port Coquitlam.

But its townhomes are out of the reach for median family incomes — a household would need to make $123,183, but the income there is less than $120,000.

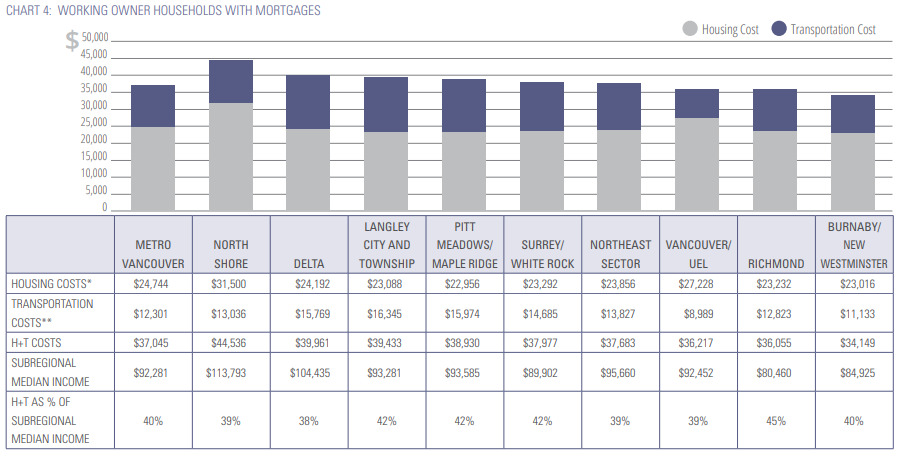

There are additional problems when it comes to buying a townhome in a suburban community that families can afford: the transportation costs pile up quickly.

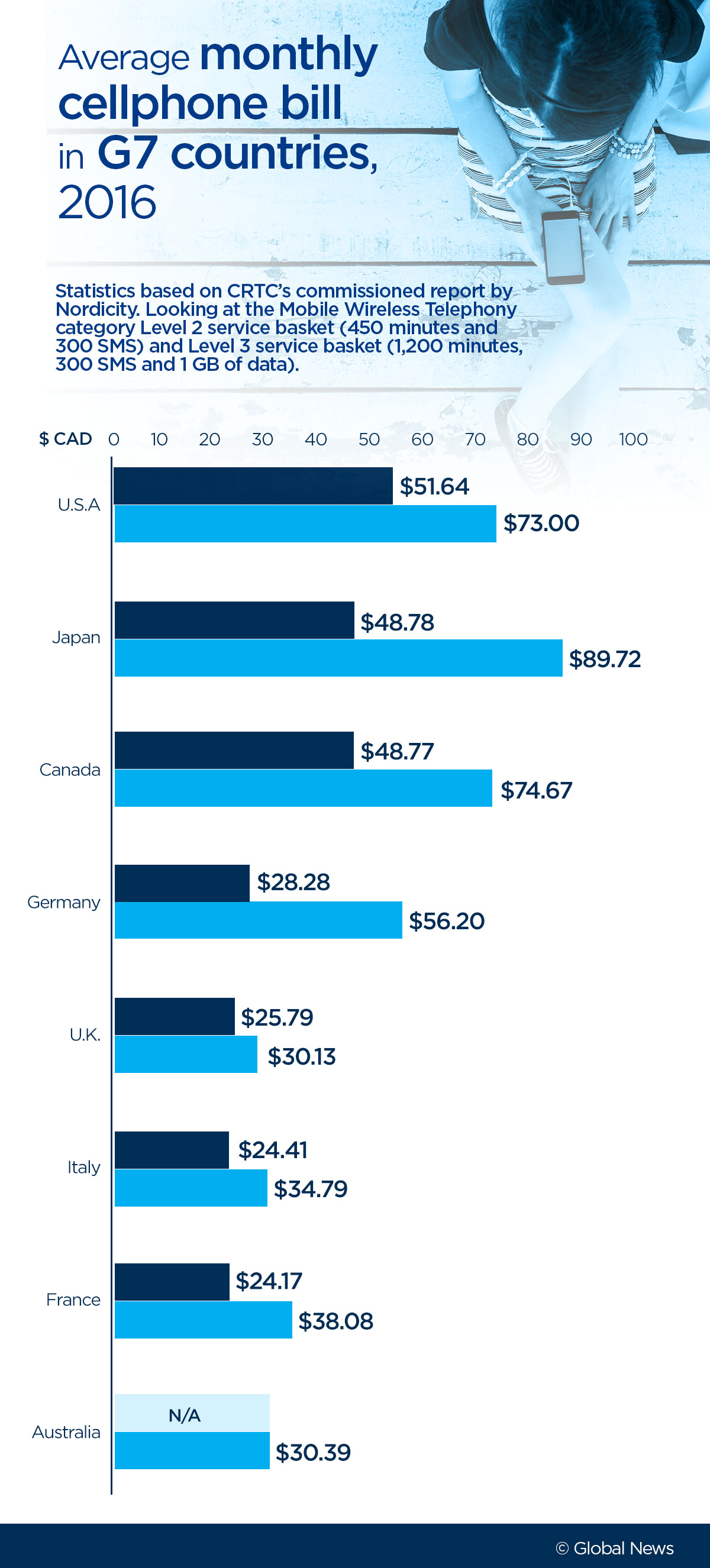

In the Township of Langley, for example, a household would need to make $102,458 to afford a townhome. That’s well within the median family income of $126,099.

But transportation costs there can total over $16,000 per year; in Vancouver, they’re $8,989, according to a study out of Metro Vancouver’s regional district.

The total cost of living in Vancouver actually comes out cheaper when you consider these expenses.

In other words, living far out from a city centre offers what Yan called a “phantom affordability.”

“What looks affordable isn’t when you factor in transportation costs,” he said.

What do we do about it?

But how does one fix a situation where incomes can’t support homes — and can’t easily support transportation costs where homes are more affordable?

“For Vancouver to become truly affordable, the housing values will have to go in half, or you’re going to have to double median household incomes,” Yan said.

Both are extreme prospects — Vancouver would have to experience what Las Vegas housing did in the 2008 recession, he said.

That, or incomes would have to go up in the way they did when Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping introduced reforms that lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty, and are unrealistic today.

Ultimately, Yan thinks it’s first important to identify the depth of a problem, and then come up with solutions.

The latest data, he said, helps to define the problem, as opposed to just “running for solutions.”

Yan resists proposals like a mass rezoning of single-detached home lots, as the City of Vancouver is currently considering — it’s one he calls the “plastic straw ban of housing policy.”

“You’re going to need something more,” he said.

“Housing policy that acts more like a scalpel than an axe.”

Detailed Methodology:

Incomes were calculated using a series of metrics.

First, Global News took benchmark home prices for single-detached homes, townhomes and apartments as reported by the Greater Vancouver and Fraser Valley real estate boards in August 2018.

Property tax bills were estimated for each of these home types by applying 2018 rates to the benchmark prices — not to homes’ assessed values. The basic homeowner grant was applied to these metrics.

Estimates for heating costs were provided by BC Hydro and RateSpy: they were $150 for single-detached homes, $60 for townhomes and $38 for apartments.

Strata fees proved the most complex metric to include; estimates of such fees are difficult to come by. Global News came up with estimates by taking MLS listings for townhomes and apartments in every Metro Vancouver community cited in this study, and then generating a median for each area and housing type.

Global News also assumed monthly non-mortgage debt of $1,163 — this figure was three per cent of the average consumer non-mortgage debt in Vancouver for the first quarter of 2018, as reported by TransUnion.

All of these figures were then plugged into an intelliMortgage calculator with a 20 per cent down payment, a 30-year amortization and a qualifying interest rate of 5.44 per cent, which is more than the Bank of Canada’s posted rate for a five-year conventional mortgage (5.34 per cent).

Exceptions were made for homes worth more than $2 million — these were calculated with a 30 per cent down payment.

They underwent two calculations: one to account for the Total Debt Service (TDS) ratio, another for the Gross Debt Service (GDS) ratio.

These calculations generated an income needed to afford a home at a particular price.

Home price data did not match municipal boundaries precisely.

North Vancouver, for example, is reported as a single area by the Real Estate Board of Greater Vancouver (REBGV), even though it is separated into a district and a city.

Langley, meanwhile, is also reported as a single area by the Fraser Valley Real Estate Board (FVREB), despite being divided into a city and a township.

In these cases, the analysis applied the same home price to both cities, as well as the township and the district, but adjusted for different estimates for strata fees and property taxes.

Incomes also weren’t divided along the lines used by the real-estate boards. Vancouver West and Vancouver East, for example, were calculated using the median total income for economic families with children that the census reported for all of the City of Vancouver.

The same was done for the separate regions of Burnaby and Surrey.

Comments