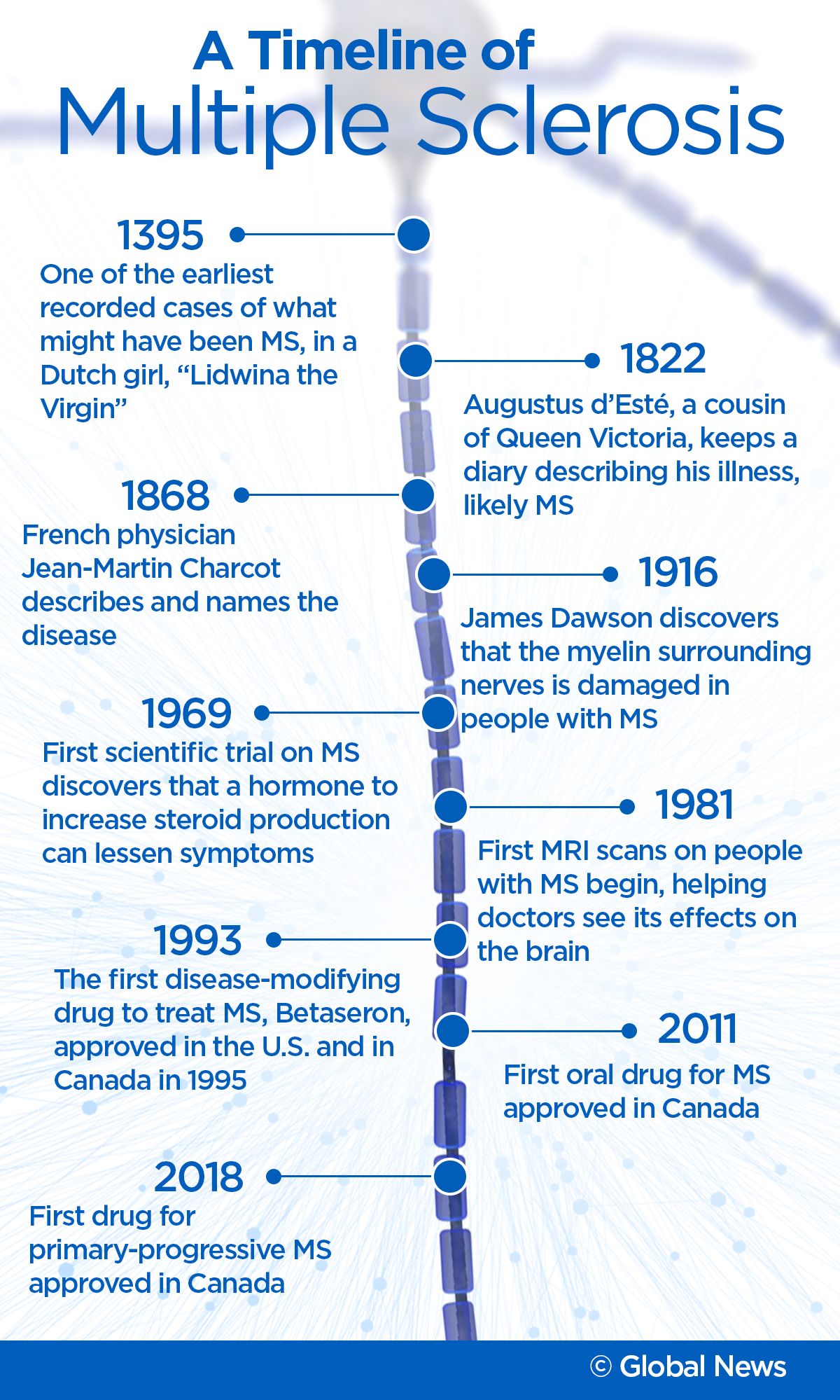

Multiple sclerosis has been affecting people for centuries, if not longer. But most of the progress in our understanding of the disease has come in just the last few decades.

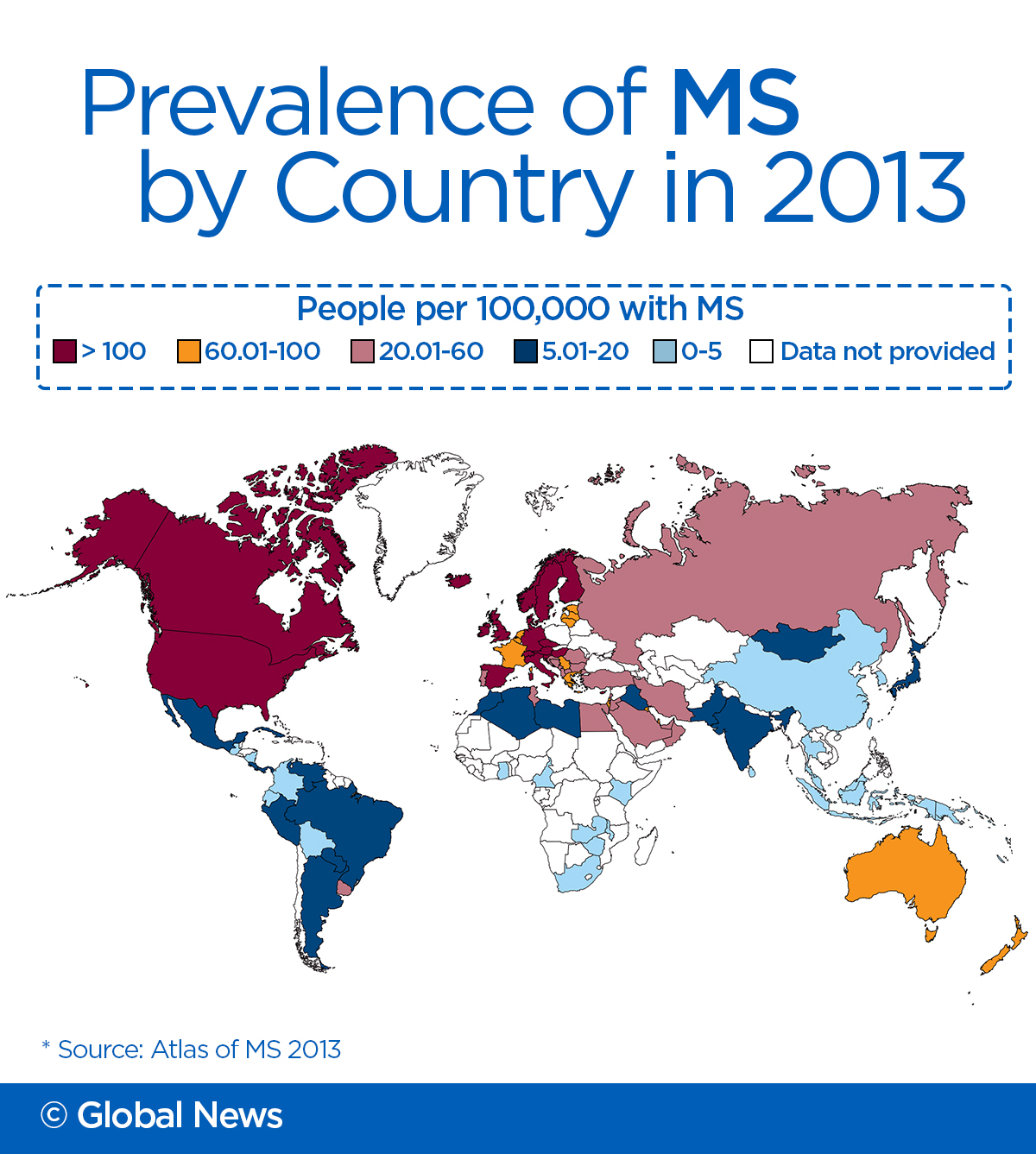

It’s estimated that over 93,500 Canadians of all ages currently live with MS – an inflammatory neurological disease of the central nervous system that impacts one’s brain, spinal cord and optic nerves – and the Public Health Agency of Canada anticipates that number to rise to 133,635 by 2031. Canada is the country with the highest rate of MS in the world, Statistics Canada reports – and while there are theories as to why that is, the ultimate cause of MS remains a mystery.

Researchers are working on it though.

According to MS researcher and historian Dr. Jock Murray, descriptions of diseases that could have been MS have appeared in the historical record for centuries. But it wasn’t until 1868 that Jean-Martin Charcot described and named the disease.

“Once you have described something very clearly and given it a name, other people can then diagnose it,” said Murray. Within a few years, doctors all around the world were starting to diagnose cases. And, they started to notice patterns.

“They recognized there was a genetic component. And they recognized that there was a geographic distribution of the disease around the world.”

It was more common in temperate climates, and less common in countries near the equator. Doctors eventually realized that it was an auto-immune disease, where the immune system attacked the coating on cells in the central nervous system.

But although doctors were now able to identify the disease, they had no idea how to treat it.

“The one thing they were sure of was the large array of therapies that were being recommended to people with MS had no effect,” said Murray.

WATCH: A look at how far MS research has come

The first effective drug to slow the progression of MS, Betaseron, was only approved in 1993 in the U.S., 1995 in Canada. Now there are 14, according to the MS Society of Canada – and the first drug to treat primary-progressive MS (PPMS), for which there were no treatments, was approved by Health Canada in February.

This is “a far cry from when I was a neurology resident back in the ’80s and the attitude back then was when we saw MS, we were afraid to tell patients that they had it because we had nothing to offer them,” said Dr. Mark Freedman, an MS researcher at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute.

Diagnosis

One thing that has helped MS patients is advancements in diagnosis. “If you look at MS before this modern era the average time from first symptom to when patient was told they have the disease was somewhere in the order of 10 years and now it’s in the order of probably minutes,” said Dr. Jack Antel of the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital and McGill University.

“Because we have potential therapies we think that the earlier you intervene, the more you spare damage to the brain,” he said.

MRI can show areas of the brain damaged by the disease, which allows doctors to diagnose it and track its progress, as well as determine whether a particular drug is slowing that progress.

Having this diagnostic capability, along with more advanced therapies, has made a “tremendous difference,” he thinks.

WATCH: A technician at the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital reviews a MRI scan for MS.

New treatment options

There have been snags in research though. In 2009, an Italian doctor claimed that something called “liberation therapy” to unblock certain veins in the neck could vastly improve symptoms. Although there was a lot of excitement in the MS community and many patients rushed to receive the treatment, “there was no biology to support it,” said Antel.

Still, research continues. Freedman and others like him are working on new drugs. One promising area is “re-myelination”: drugs that would help to repair the nerve damage caused by the disease.

Another area he is researching is what happens when you combine several drugs – a therapy that has worked well for patients who have conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and AIDS. Although two of Freedman’s trials have shown promising results, the cost is prohibitive: many MS drugs cost $15,000-$20,000 per year, so drug insurers and provincial governments are reluctant to buy several for a patient to take at once, he said.

WATCH: Dr. Mark Freedman of the Ottawa Hospital discusses MS treatment advances

Clinical trials

Freedman has also been exploring stem cells and surgical options to treat the disease.

In 2016, he and co-author Harold Atkins published the results of a 13-year clinical trial. Doctors harvested stem cells from MS patients. Then, they killed off the patient’s immune system using a combination of drugs.

“Once the immune system is triggered to attack it remembers. And every time it sees what it regards as the enemy, it will attack again and again and again.”

“We determined a concoction that we felt would remove all of the immune system and more importantly the memory that is stored within it,” he said.

Via a bone marrow transplant, the stem cells are put back into the patient to regrow their immune system. And, it seems, the new immune system doesn’t think to attack the nerve cells.

After more than 15 years, none of the patients have experienced new MS attacks. “Surprisingly, many of them, who had fairly significant impairments already started showing signs of recovery.”

Jennifer Molson was one of those patients. Diagnosed with MS in 1996 at the age of 21, just five years later she had to stop working because her symptoms had become so severe.

WATCH: Jennifer Molson’s MS improved after she took part in a clinical trial

“My boyfriend at the time, Aaron, he’s my husband now, was looking after me and helping me bathe and dress and cut my food,” she said. She had tried all the drugs available – there were only four at the time – and none had had much of an effect on her progression.

When offered the chance to participate in the stem cell trial, she took it. “At that point, it seemed pretty good because I knew how my life would be if I didn’t take this shot.”

The process was “horrific,” she said, taking aggressive chemotherapy, being hooked up to machines to harvest stem cells, and a difficult recovery. “It was gruelling. It took me at least a year to feel like I did before the transplant, in terms of not throwing up, feeling human again.”

But months later, in her condo, she realized she was walking down the hall to her mailbox without bringing her canes. “Then I’m cutting food, and I’m going to the grocery store and I’m not tired. I’m going out with my friends.”

Three years later, she decided to go back to work.

Now she’s 42 and although she still wears a wig after the chemo, takes hormone replacement therapy for the chemo-induced menopause and is on antiviral drugs after several bouts of shingles, she’s happy she did it. “We’ve gotten our lives back.”

The process isn’t for everyone, and it carries high risks too, said Freedman. “When we started that, we had to quote a one in 20 chance of dying.”

“One in 20 is pretty high. If you had a one in 20 chance of winning the Lotto Max, you’d be out buying tickets like crazy.”

One trial participant did die, but the procedure has now been performed roughly 60 times, he said. He’s not sure what the long-term effects of the treatment are though, as he hasn’t been able to follow the patients long enough. “We know that we’ve controlled their MS but I can’t tell you that 30 years later we haven’t done anything that’s worse.”

He’s hopeful that other therapies might advance enough that patients won’t need to undergo a bone marrow transplant to control their disease.

Unanswered questions

To Murray, there are still a lot of unanswered questions about MS. Although scientists know that the disease occurs when the immune system attacks the myelin of the neurons. “But then you have to say, why does the immune reaction happen? Because the brain doesn’t normally have immunologically active cells circulating in the brain.”

Scientists also seem to think that there is a link between low levels of vitamin D and MS, though they’re not sure whether taking supplements has any effect on the disease.

Murray is also interested in the long-term effects of the various drugs. Because the first was only approved in 1993, scientists haven’t been able to observe what happens when someone takes one for 40 years.

Molson feels there are a lot of reasons to be optimistic about the future of MS research. “Even in 16 years where we’ve come in terms of research and drug therapies for MS is very different from what we had when I got my transplant.”

“I think it’s really exciting right now in the field of MS research. We’re looking at a lot more hope for a lot more patients that treatments weren’t available for before.”

Part 4 of Brain Interrupted, our series on multiple sclerosis, will be published May 17 at 6 a.m.

Comments